PREFACE

When I first met Capt. Doug Zembiec in 2004, he was sitting on the roof of a shot-up house, nibbling on a cracker and shouting into a headset over the cracks of rifle fire. The fierce battle for Fallujah had been raging for weeks. Black stubble covered his cheeks and his eyes were bloodshot. He flashed a wicked grin and said, Welcome to chaos.

Crouched behind the sandbags lining the rooftop wall, two snipers sat hunched over rifles with telescopic sights. Zembiec pointed to a few insurgents darting across a street several hundred yards away. One sniper fired a .50-caliber shell, big as a cigar, and the recoil rocked him back. The other took a shot with a smaller M14 rifle. The corporal with the M14, he said, has more kills. If we keep knocking them down out there, theyll get the message.

An All-American wrestler while at the Naval Academy, Zembiec took care of his men, adored his wife and baby daughter, bragged about his dad, shared food with the civilians hiding downstairs, stored the china away from the bullet-shattered windows, and shot at every insurgent. He was a fighter, an infantryman. His men had dubbed him the Lion.

I stayed with Doug and his company inside Fallujah, and several months later caught up with him again on patrols outside the city. We stayed in touch and just missed linking up in May of 2007 in Baghdad, where his unit was hunting down al Qaeda terrorists. Later that month, while leading his team on a raid, the Lion of Fallujah was killed.

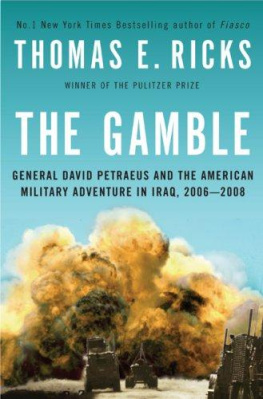

From the summer of 2003 until the fall of 2006, we were losing militarily. Sunni and Shiite extremists were threatening to break Iraq apart. Then the tide of war swung. This narrative describes how warriors like Doug Zembiec turned the war around.

There are two broad views of history. By far the more popular is the Great Man view: that nations are led from the top. Leaders like Caesar and Lincoln shape history. Most accounts of Iraq subscribe to the Great Man view. The books about Iraq by senior officials like Bremer, Tenet, Franks, and Sanchez have at their core a wonderful sense of self-worth: History is all about them.

The other view of history holds that the will of the people provides the momentum for change. Leaders are important, but only when they channel, or simply have the common sense to ride, the popular movement. Battle is decided not by the orders of a commander in chief, Tolstoy wrote in War and Peace, but by the spirit of the army.

Iraq reflected Tolstoys model. Events were driven by the spirit, or dispirit, of the people and tribes. Iraq wasnt a Great Man or a generals war. There wasnt a blueprint and scheme of maneuver akin to what guides units in conventional war. The generals were learning at the same time as the corporals. At the top, it was easiest to talk with those officials who had spent time on the lines and didnt substitute theories to cover up what they didnt know. Generals Casey, Petraeus, Mattis, and Odierno were remarkably candid, willing to share with a fellow grunt their feelings about leadership and operations. I was struck that all four used the word complex time and again. Iraq was a kaleidoscope. Turn it one way and you think you see the pattern. Then along comes some unexpected event and the pattern dissolves.

This book has two parts. The early chapters bring us through mid-2006, amidst strategic mistakes and a growing frustration among the troops. At that time, many in the States believed the only course was to leave Iraq, despite the consequences. Then came a remarkable U-turn, described in the later chapters. By 2008, the steadfastness of our soldiers and excellent leadership had reversed the course of the war.

A cottage industry has sprung up in academia to study counterinsurgency as if it were a branch of sociology. In this booka narrative of waryou meet the troops. War is the act of killing. As a nation, we have become so refined and so removed from danger that we dont utter the word kill. The troops in this book arent victims; they are hunters.

Iraq was my second insurgency. As a grunt in Vietnam, I patrolled with a Marine squad and Vietnamese farmers in a Combined Action Platoon, or CAP, in a remote village. Later, as a counterinsurgency analyst at the RAND Corporation, I visited Malaysia and Northern Ireland to look at British techniques and wrote a book, The Village, about fighting in combined units in Vietnam.

In Iraq, over a span of six years I accompanied, or embedded with, over sixty American and Iraqi battalions. In the course of hundreds of patrols and operations, I interviewed more than 2,000 soldiers, as well as generals and senior officials. In this book I also cite campaign plans, because they illustrate how senior staffs assessed the war, and how difficult it was for senior officials in Iraq, let alone the White House, to understand what was going on.

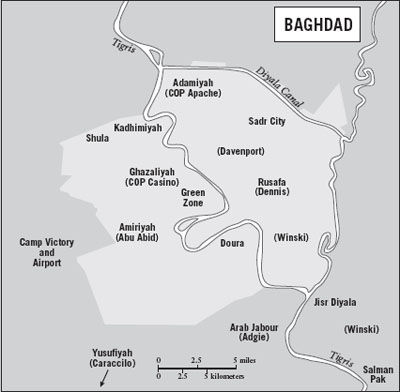

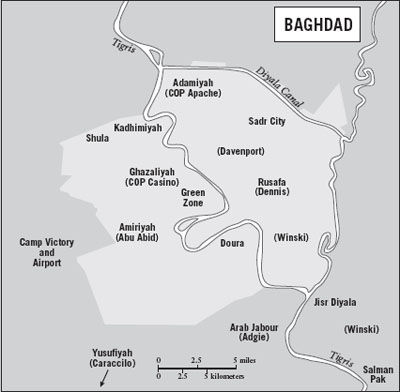

In conventional war, the locations of the battlefields change as the armies move on. In counterinsurgency war, the goal is to control a population that does not move. The adversaries fight on fixed battlefieldsthe same cities and villages. What changes is time rather than location. To describe the war, I bring the reader back again and again to the same cities in Anbar Provincethe stronghold of the insurgencyand the same neighborhoods in Baghdad, the heart of Iraq. These two locales accounted for most of the fighting and most of our casualties.

This narrative describes how the war was fought by our soldiers, managed by our generals, and debated at home. The tone is not gentle toward those at the top, military and civilian, supporters and detractors of the war alike. After Vietnam, I never envisioned that I would again know so many who died so young. What angered me after six years of reporting from the lines was how so many at the top talked mainly to one another and did not take the time to study the war. The same was true of the wars critics. The turnaround in the war went largely unacknowledged.

The generals, ambassadors, and senators will write their own books. The intent of this book is to deepen the readers understanding of the performance of our soldiers and the wars complexity. It lays out the mistakes and the learning, drawing conclusions and lessons. Our society imposed restraints and expectations that can lead to failure on a future battlefield. At the same time, no reasonable observer could watch how our military adapted without being impressed by the remarkable turnaround.