If I Could Turn and Meet Myself:

THE LIFE OF ALDEN NOWLAN

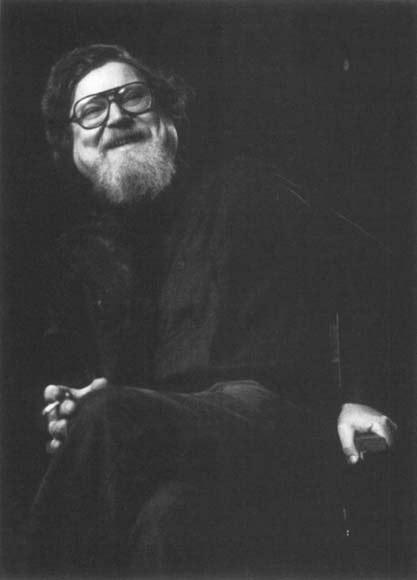

Alden Nowlan, 1982-1983. KENT NASON

If I could turn and meet myself

The Life of ALDEN NOWLAN

PATRICK TONER

Copyright Patrick Toner, 2000.

All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced or used in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any requests for photocopying of any part of this book should be directed in writing to the Canadian Copyright Licensing Agency.

Edited by Laurel Boone.

Cover photo by Kent Nason.

Cover design by Julie Scriver.

Book design by Julie Scriver and Ryan Astle.

Printed in Canada by VISTAinfo.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Canadian Cataloguing in Publication Data

Toner, Patrick, 1968

If I could turn and meet myself: the life of Alden Nowlan

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 0-86492-265-5

1. Nowlan, Alden, 1933-1983. 2. Authors, Canadian (English)20th century

Biography. I. Title.

PS8527.0798Z86 2000 C818.5409 C00-900157-3

PR9199.3.N6Z86 2000

Published with the financial support of the Canada Council for the Arts, the Government of Canada through the Book Publishing Industry Development Program, the New Brunswick Department of Economic Development, Tourism and Culture, and a grant from the Humanities and Social Sciences Federation of Canada, using funds provided by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada.

Written with the support of the Arts Branch of the New Brunswick Department of Municipalities, Culture and Housing and the Explorations program of the Canada Council.

Goose Lane Editions

469 King Street

Fredericton, New Brunswick

CANADA E3B 1E5

For Ervette Hamilton (1910-1999),

the aunt of this book.

INTRODUCTION

from The Kookaburras Song

If I could turn and meet myself as

I was then,

gaze into that solemn face, those

unblinking eyes,

I suppose Id laugh until I cried,

then laugh again.

I never met Alden Nowlan. When he died in 1983, I was fifteen and only dimly aware of his importance. Like many New Brunswickers, I was acquainted with his weekly column in the Telegraph-Journal, and knew somehow that he was a poet. Thankfully, the public education system filled some of the gaps in my knowledge.

It is hard to imagine what a meeting between us might have been like, although in the course of studying Nowlans life and art I have found myself yielding to the temptation. Part of the wonder of his writing is how he can make a reader feel as though the two of them are sitting together in a quiet room having a profound and intimate conversation. But I know from first-hand accounts what such conversations with Nowlan the man were sometimes like: one-sided affairs in which the poets audience was expected to listen, not to dispute or especially to probe.

What would our conversation have been like, then, given the fact that as a biographer I could not have helped but prod this great bear in an attempt to elicit answers? I may have earned a growl for my pains, although Nowlans friend Leo Ferrari, in a memoir published recently in the Telegraph-Journals supplement The New Brunswick Reader, suggests a more gentle yet equally frustrating result. Ferrari relates an incident in which a student interviewer bent on extracting the truth from Nowlan was subjected, not to insults and browbeating, but instead to continual interruptions when the poet lumbered out to the kitchen on some mysterious errand, always returning smelling more strongly of gin. The interviewer, at length reduced to shouting questions at an inert mass nearly passed out in his La-Z-Boy, gave up the exercise. With both passive and active weapons at his disposal against such interlopers, Nowlan doubtless would have proved to be a challenging subject, though not an impossible one. Possessed of probably the most intimate and confessional voice in Canadian letters, he could be gracious and accessible to interviewers who came with the right spirit, provided they came on his terms.

Anne Greer, the first person to conduct serious biographical research on Nowlan for her 1973 MA thesis, was one of those lucky ones who was able to earn his trust. She described to me her fascination with the poet, stemming from the almost archetypal quality of his life and writing. Michael Brian Oliver, another writer who has taken a serious look at how Nowlans life affected his art, echoes critic Milton Wilsons observation that Nowlans writing lies in the realm of mythology; they describe his work as pre-literary. When I interviewed Leo Ferrari for my own 1993 MA thesis on the religious imagery in Nowlans poetry, he characterized his friends life as a deliberately created thing, much like one of his own poems or stories, something fashioned as he went along.

Much the same can be said for any of us: we all fashion our lives as we go along, plucking the threads that please us from a formless and tangled ball and weaving them into a fragile pattern that shifts and changes as the ball accumulates random straws, hairs and bits of dust. Nowlan was one of those for whom the process of weaving his life took on a life of its own. He came to believe that the small scrap of fabric he had created could stretch to cover a tangled, chaotic ball growing bigger by the day.

Springing from an impoverished Nova Scotia family that had few possessions and no power, he claimed the one thing he could control: his own story. During his early childhood, he could control little else. Young Alden was abandoned by nearly every adult he depended upon in an environment that offered emotional shelter as meagre as the physical shelter provided by his fathers house. Nevertheless, he returned obsessively to this world in his writings. Though he speaks of his imaginative world as a means of escape, he could not pull away from the harsh reality of his youth. He had to return if only symbolically to impose his will on the time and place that once held him captive, as he says in his poem The Boil, now/at last/master/rather than/servant/of the pain.

Dealing with the question of truth in Nowlans fiction and life is a frustrating exercise, like the poser of the box surrounding the statement Everything inside this box is a lie or the M.C. Escher drawing of two hands each sketching the other with a pencil. What does it matter whether Nowlan (or, for that matter, any other writer) is telling the factual truth, the underlying truth or the personal truth in his writings? Are writers not paid to tell lies? Perhaps. But Nowlans readers accepted that what he was writing was the truth, and, more significantly, he came to share that belief. It is not necessary to go to the indefensible extreme of assuming that the I or the Kevin OBrien of his poetry and fiction is the literal Nowlan, that, for instance, he literally did go to the store one day for a loaf of bread and returned with a new life in a different world. What is important is that Nowlan believed that this is what happened. If his oeuvre has an over-arching theme, it is that people must own their own lives, really own them, with all their bread, wine and salt, their tears and laughter. If I Could Turn and Meet Myself examines the price Nowlan paid to own his life, and it asks whether sometimes he may have paid too much.

Next page