Contents

Guide

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

For Esther Davidowitz

It is human to enjoy fame, especially when you have reason to suspect that you have earned it.

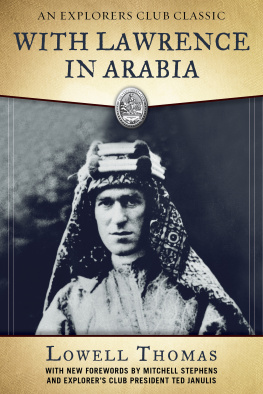

L OWELL T HOMAS

Two very different men began to circle each other in Jerusalem in February 1918. One was attired in full Sheikhs costume, as an acquaintance put it, including robe, keffiyeh and dagger. He walked the streets barefoot. The British had just liberated, as it was then put, Jerusalem from the Ottoman Empire, and, despite the outfit, this man was a major in the British Army.

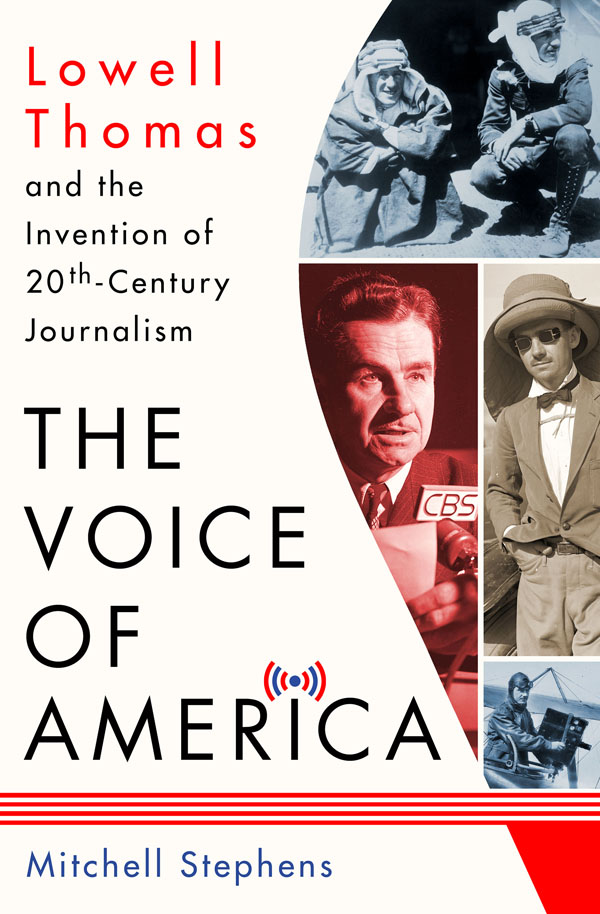

The other man, always well turned out, would have been wearing a good pair, as he put it, of English field boots and crisp, military-like garb, although he was not enlisted in any of the armies then fighting the First World War. His name was Lowell Thomas, and, according to a journal Thomas was keeping at the time, he had first met Major T. E. Lawrence in the office of the military governor of Jerusalem. Thomasoften ready to improve a storylater maintained, however, that he had started tracking down this mysterious blue-eyed, beardless man in Arab dress after spotting him on the streets of Jerusalem.

Lawrence, who had graduated Oxford with first-class honors in modern history, was leading, or helping lead, or tagging along on (his biographers have long tussled over which) the daring and successful Arab Revolt against the Ottoman Empire. Lawrence too was known to fiddle with a story. He was almost 30, although Thomas noted in his journaland this was probably Lawrences fibthat he was 28.

What Lowell Thomas was doing in the Middle East was not entirely clear. He was a 25-year-old American from a gold-rush town in the Rocky Mountains who had recently resigned from the faculty at Princeton University. Thomas had attended law school and worked on newspapers before that. More recently he had enjoyed some success presenting illustrated travelogues. If this seems today a rather varied rsum, rest assured it seemed that way then too. Based on this hodgepodge of experiences and a formidable persuasiveness, Thomas had raised money to pay for his loosely defined effort at journalismor propagandain support of the American, and by extension the British, war effort. He had brought along a skilled still and film cameraman, this more than four years before Nanook of the North , the first commercially successful full-length film documentary, was released. But there is no evidence that Thomas, though he took a lot of notes and shot a lot of film, sold any journalism while in the Middle East.

Why Thomas would want to be in this part of the world at this moment is easier to divine: Thomas was not the sort to miss a good story or a good adventure, and the capture of Jerusalem offered both. He also was not the sort to let doubt about what he was doing interfere with getting something done.

Thomas was introduced to Lawrence. They talked and talked again, with Thomas taking notes. Lowell recognized that an Englishman in Arab robes leading (Thomas acknowledged no controversy here) a group of Arabs on camels in successful desert raids against one of Britain and Americas enemies was news. With cameraman in tow, he arranged to follow Lawrence into the desert.

This would prove a life-changing encounter for both men. To what extent it was responsible for the celebrity that was about to afflict Lawrence of Arabia is also a matter of controversy. Some of Lawrences biographers maintain that even without Thomas he would have been recognized as one of the heroes of a war that produced few heroes and would have achieved considerable renown. It offends those biographers to cede much credit to the messengerthis entrepreneurial, storytelling, uncredentialed American messenger. And Lawrences exploits, even subtracting those in dispute, were indeed dramatic; he was a fascinating man.

But there can be no argument as to how Lawrence actually did first come to the attention of the worldincluding most of his compatriots. The vehicle was a show combining narration and music with slides and documentary film footage. The show was conceived, reported, written, narrated and produced by Lowell Thomasmore than a year after he met Lawrence. Thomas thought of it as a wholly new and spectacular form of entertainment. The genre? Part travelogue, part theater, part newsreel, part proto-documentary. It was also, by some definitions, the first multimedia work of journalism. And the star of Thomas productionseen in slides and film shot in Jerusalem, Arabia and, secretly, Londonwas Lawrence, the Uncrowned King of Arabia.

About two million people around the world paid to watch and listen to Thomas show. The audiences in London included the queen, the prime minister and, on more than one occasion, Lawrence himselfdoing his best not to be recognized. In 1924 a book on the subject, With Lawrence in Arabia , appeared and became an international best seller. It was written by the only journalist (or propagandist) to have interviewed and traveled with Lawrence in the Middle East: Lowell Thomas.

Lawrence died in a motorcycle accident 17 years after first meeting Thomas in Jerusalem. After the war he had made one other major historical contribution: lobbying at postwar conferences for Arab independence and in the process helping draw, for better or worse, the modern-day borders of the Middle East.

The Lawrence story obviously gave a hefty boost to Thomas career. The shows and then the book, his first, were at the time the biggest successes in this young mans already extraordinary life. They provided his own first taste of fame. But Thomas would have many more successes and experience much greater fame.

In the 63 years he lived after first meeting Lawrence, Lowell Thomas contributions to twentieth-century American journalismon radio, in newsreels, on televisionwould be as significant as anyones. Much of the distance between a wild Hey, sweetheart, get me rewrite Chicago-style journalism and the sober, Olympian And thats the way it is journalism of Walter Cronkite was covered by Lowell Thomas. Thomas became one of the handful of individuals who might claim to have been the most creative and most successful American journalist of the twentieth century. For a decade or two of that century, he was the best-known American journalisthis voice as familiar as anyones through his nightly radio newscast, his face, with its neatly trimmed mustache, easily recognizable as that of the on-screen host and narrator of the most popular twice-weekly newsreels.

And Thomas never stopped racing hither and yon: to Europe and the Middle East; to India, Afghanistan, New Guinea and, among countless other places, Tibetthen closed to outsiderswhere he met with the young Dalai Lama right before the Communists marched in. The Explorers Club has named its building, its awards and one of its main dinners after Lowell Thomas.

His memoir sometimes reads like the Perils of Pauline: an airplane in which Thomas is riding makes a crash landing; a large, angry crowd is about to go after him and his fellow foreigners; bullets whiz by or penetrate his hat. Mention these incidents to those who knew him, and they smile. He liked a good story, theyll say softly. But Thomas was in all those early, rickety airplaneswhen air travel was still brand newand he did visit an extraordinary number of out-of-the-way, even dangerous places. On the way back from Tibet, Thomas pony threw him, and with his leg broken in eight places, Thomas had to be carried down from the Himalayas.