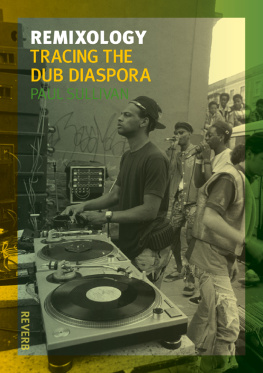

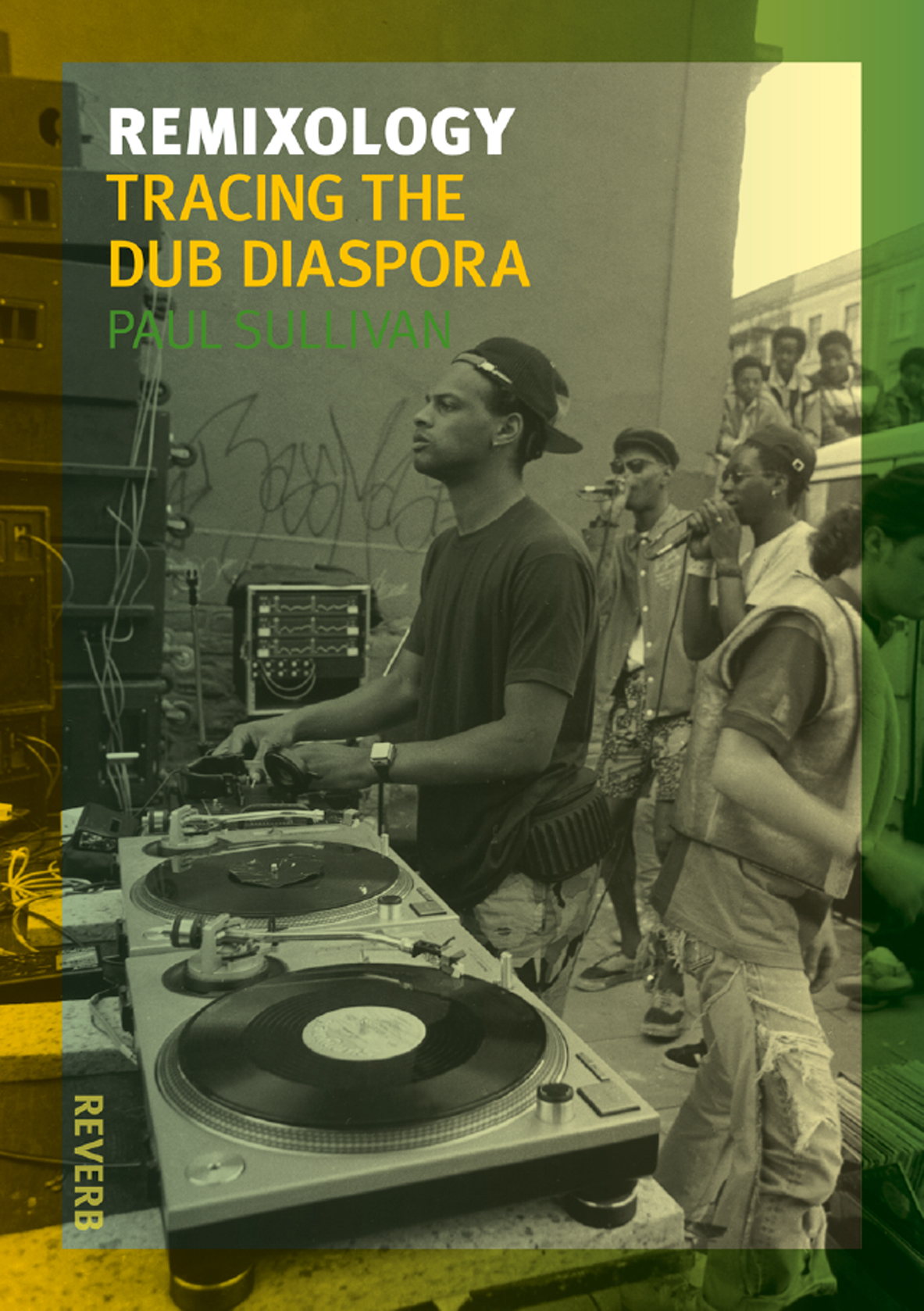

REMIXOLOGY

The Reverb series looks at the connections between music, artists and performers, musical cultures and places. It explores how our cultural and historical understanding of times and places may help us to appreciate a wide variety of music, and vice versa.

reverb-series.co.uk

Series editor: John Scanlan

Already published

The Beatles in Hamburg

Ian Inglis

Brazilian Jive: From Samba to Bossa and Rap

David Treece

Nick Drake: Dreaming England

Nathan Wiseman-Trowse

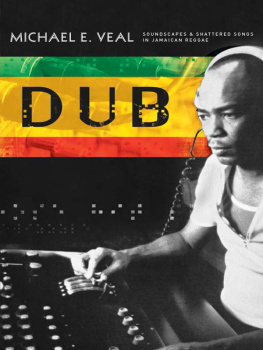

Remixology: Tracing the Dub Diaspora

Paul Sullivan

Tango: Sex and Rhythm of the City

Mike Gonzalez and Marianella Yanes

Van Halen: Exuberant California, Zen Rocknroll

John Scanlan

REMIXOLOGY

TRACING THE DUB DIASPORA

PAUL SULLIVAN

REAKTION BOOKS

Published by Reaktion Books Ltd

33 Great Sutton Street

London EC1V 0DX, UK

www.reaktionbooks.co.uk

First published 2014

Copyright Paul Sullivan 2014

All rights reserved

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publishers.

Page references in the Photo Acknowledgements and

Index match the printed edition of this book.

Printed and bound in Great Britain by Ashford Colour Press, Gosport, Hants

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

eISBN: 9781780232102

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

People get warped by dub and they never recover.

Ian Penman

Ethereal, mystical, conceptual, fluid, avant-garde, raw, unstable, provocative, transparent, postmodern, disruptive, heavyweight, political, enigmatic dub is way more than a riddim and a bassline, even if it is that too. Dub is a genre and a process, a virus and a vortex; it draws the listener into a labyrinth, where there are false signposts and mercurial trails that can lead to the future, the past or to nowhere at all. It is apposite that the etymology of this so-called aural magic realism lies in the tricknological process of manipulating sound on film; that is, doubling or dubbing and the ghoulish habit of re-recording voices onto a soundtrack. And there is a neat coincidence too, perhaps, that the Jamaican patois word for ghost, taken from the Obeah (a set of beliefs and practices developed in the West Indies), is the similar-sounding duppy.

In Kingston, the capital of Jamaica, where dub was first created, dubplate was the term used for acetates on which instrumental versions of popular tunes to be tested out on sound systems were pressed. These dubplate versions were initially instrumentals of roots reggae songs, which became popular on the Kingston circuit after sound system operator owner Ruddy Redwood cut an acetate of On the Beach by The Paragons (1967) at Duke Reids Treasure Isle studio, and engineer Byron Smith accidentally left the vocals out.(Wassy) and a bemused but excited crowd to fill in the gaps with their own voices. Engineers and producers took the concept of the instrumental a step further by not only removing the vocals, but using multitrack technology to delete, add or rearrange other elements (drums, guitars, bass) and adding further studio effects such as reverb and echo.

Dub versions were a boon for record producers and labels looking for B-sides for their 7-inch (45-rpm) records. Recording new songs for this purpose was costly and using the rhythm track of the A-side not only saved money but allowed the sound system selectors to talk over the track. While the concept of version, i.e., mainly instrumental takes on pre-written songs, has a history prior to dub (specifically in African-American and Caribbean music forms like jazz, blues and salsa), its Jamaican variant was unique, owing to the levels of modification involved.

Although technology had been used to open up and rearrange music before, by musique concrte artists, for example, and Western music producers, like George Martin and Teo Macero, the concept of the mixing-board-as-instrument (and its corollary, the engineer-as-artist) was fully realized in Kingston. The way in which the dub pioneers (with Lynford Anderson, Errol Thompson, Augustus Pablo, King Tubby, Keith Hudson, Lee Scratch Perry among them) began deconstructing songs into their constituent parts then rebuilding them into alternative compositions literally turning them inside out to reveal their seams made the music simultaneously avant-garde and hugely popular with the sound system crowds.

The importance of the sound system cannot be understated in the development of dub, not only because of the dissemination of the music, but also because of its role in the musics creative evolution. This reduction of songs to shadow and suggestion prefigured the concept of the remix, as well as laying the foundations for the birth of rap and the phenomenon of the MC, when the sound system deejays filled in the absences with their hype. Sound system selectors and operators, meanwhile, were the first incarnation of the modern DJ where the voice was contained in a studio. They broke through the remoteness of radio broadcasts to provide a physical conduit between the playing of pre-recorded music and the audience.

Although dub was, and is, a more or less fluid process with no rigid rules, certain sonic tropes are recognizably consistent when tracing its development. Chief among them are reverb and delay (echo). Although they are often confused as the same thing, there is a slight technical difference. Reverb can be defined as repetitions of a sound that occur within a few milliseconds of the sound being made, and which the brain perceives as originating from the same location. Singing in the shower is an example of reverb. Delay/echo carries a more distinctive repetition than reverb as it clearly comes from a different place than the source material. Shouting into a cave is an example of echo.

Reverb and echo have been used in various forms of music, from rhythm and blues and country music (Muddy Waterss or Elvis Presleys recordings on Chicagos Chess Records or for Sun Records in Memphis, for example), to Western classical music, where studios have employed these techniques to simulate acoustic settings such as churches and cathedrals.

But dubs originators, most of whom were engineers, used echo and reverb to reunify fragmented songs as well as to disorient the listener, as though pulling the rhythmic rug from under their feet. Such an approach often produced psychedelic results, and gave the music a trippy reputation that persists today. As Erik Davis memorably put it, good dub sounds like the recording studio itself has begun to hallucinate.

Since echo is also related to human memory (the human brain codes the remnants the echo of a memory), it can be used as a tool to transport listeners to the past. Jamaicas dub pioneers used echo in combination with the sentiments and spirituality of roots reggae to provoke a sense of Jamaicas ancestral African roots, while at the same time invoking the infinity of the cosmos and the future by creating cavernous spaces within the music.

Another major characteristic of dub is its emphasis on bass. Early dub mixes were also known as drum and bass mixes, referring to their stripping down of the music to its bare rhythmic components. The bassline occupied an increasingly foregrounded role and was subsequently intensified.

In Dub in Babylon, Christopher Partridge points out how