Published by The History Press

Charleston, SC

www.historypress.net

Copyright 2015 by Jon Talton

All rights reserved

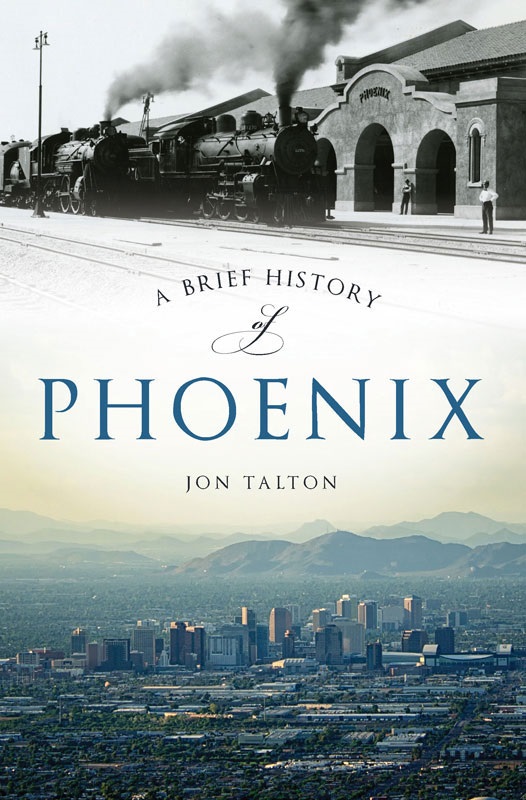

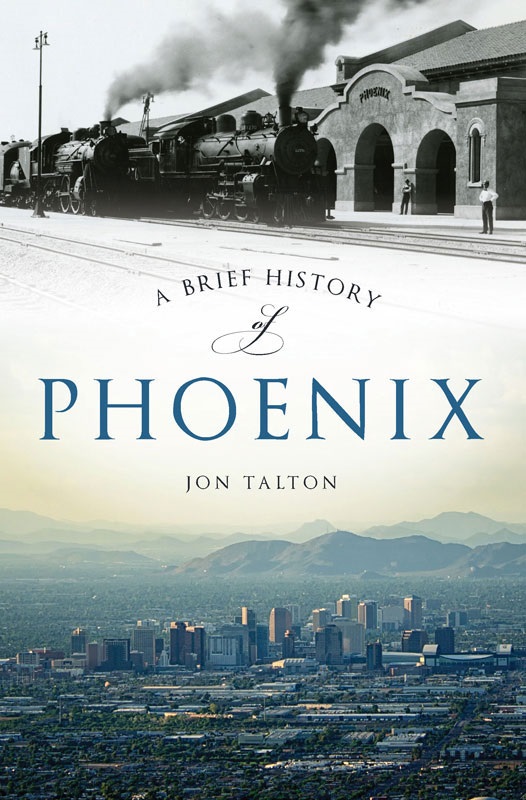

Front cover skyline by Matt Ottosen | Ottosen Photography.

First published 2015

e-book edition 2015

ISBN 978.1.62585.648.7

Library of Congress Control Number: 2015948830

print edition ISBN 978.1.46711.844.6

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the author or The History Press. The author and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

For Susan

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

In writing this work, I have depended on a rich body of scholarship about Phoenix, as well as the help of academics, archivists, urban activists and longtime residents. The three foundational scholars of Phoenix are Philip VanderMeer, William S. Collins and the late Bradford Luckingham. Each has produced one or more excellent works of history on the city and metropolitan area. Thomas E. Sheridans book Arizona: A History is the best single-volume history we have yet about the state. We are all in debt to Thomas Edwin Farish, who was commissioned by the legislature soon after statehood to write a multi-volume history of Arizona. Farish, who knew many of the pioneers personally, remains a rock-solid source. The definitive examination of Phoenixs sustainability and environmental issues comes from Andrew Ross. Jack August Jr. has brought his wide-ranging talents to a number of Phoenix and Arizona projects but is especially valuable in chronicling water issues. August was unfailingly helpful and patient in answering my questions.

I am in debt to Rob Spindler, university archivist and head of archives and special collections at the Arizona State University Libraries. He was especially helpful in guiding me through thousands of photographs in the universitys collection. Other photographic help came from Michael Ging, Brad Hall and Jeremy Rowe, as well as Wendi Goen of the Arizona State Archives. Professor David William Foster at ASU provided insights into Phoenixs barrios, Hispanic art and visual and written representations of the city. Will Bruder deepened my understanding of the citys architecture and design. The Phoenix Police Museum was helpful in detailing some of the citys law enforcement and crime history. Ive spent most of my adult life looking through the archival treasures of the Phoenix Public Librarys Arizona Room; it is an amazing resource.

While I was a columnist at the Arizona Republic from 2000 to 2007 and afterward writing the blog Rogue Columnist, I benefited from conversations and interviews with so many who helped me understand Phoenixs past, present and potential futures. I am especially grateful to Jim Ballinger, Betsey Bayless, John Bouma, Alan Brunacini, Don Buddinger, Reid Butler, Sam Campana, Chad Campbell, Jose Cardenas, Jerry Colangelo, Lattie Coor, Michael Crow, Cindy Dasch, Karl Eller, Nan Ellin, Roy Elson, Greg Esser, Jonathan Fink, Grady Gammage Jr., Neil Giuliano, Terry Goddard, Phil Gordon, Pam Goronkin, Alfredo Gutierrez, Walt Hall, Art Hamilton, William Harris, Dan Hunting, Kimber Lanning, Cal Lash, Richard Mallery, Carol McElroy, Pat McMahon, Jim McPherson, Rob Melnick, Ioanna Morfessis, Margaret Mullen, Mark Muro, Naaman Nickell, Jim Pederson, the late Jack Pfister, Elliott Pollack, Wayne Rainey, Skip Rimsza, Claire and Henry Sargent, Dan Shilling, Greg Stanton, Bill Stephens, Jeffrey Trent, Feliciano Vera, Mary Jo Waits, Quinn Williams, Ed Zuercher, the late John J. Rhodes and the late Newton Rosenzweig.

Megan Laddusaw of The History Press approached me about writing this book, and I appreciate her professional skill, care, good cheer and patience, as well as that of her colleagues.

I was fortunate to have Marshall Trimble, who spent years as Arizonas official state historian, as one of my teachers at Coronado High School in Scottsdale. He helped stoke my lifelong appetite for local and state history. So did my mother, Vivian Talton, and grandmother, Ella Darrow Hammons, who lived much of it. The author Tom Zoellner encouraged me to move from journalism and fiction to writing a history of my hometown. His example is an inspiration. I am most grateful to my wife, Susan Talton, who fell in love with Phoenix and me, despite our flaws and paradoxes.

A note on language: to be true to local convention, I refer to all whites as Anglos.

Introduction

SO BIG

In 2006, the census bureau reported that Phoenix had overtaken Philadelphia to become the nations fifth most populous city.

This was quite an accomplishment for a place that had barely entered the ranks of the one hundred largest cities in 1950, at number ninety-nine. Other American cities, such as Chicago in the late nineteenth century, had grown faster. But none was in such a hostile environment and isolated location. None among the very biggest was so relatively young. Phoenix was settled in the late 1860s but didnt become what would be considered a big city until 1960, when its population was 439,170 and it ranked number twenty-nine. The only one close was Oklahoma City, settled in 1889 and, thanks to its oil boom, a sizable city three decades earlier than Phoenix. But by 1960, Oklahoma City ranked only thirty-seventh in population. When the census made its 2006 estimate, Phoenix was about three times the size of its nearest cousin among young cities.

Some say that all Phoenix ever wanted was to get big. While an oversimplification, the statement carried some truth. Generations of Phoenix boosters, builders and visionaries imagined that a tiny farm town would become a large and great metropolis. Especially in the decades after World War II, the city became obsessed with population numbers to the exclusion of almost all other measurements. And they had always continued to grow. Census numbers, whether estimates or the hard data every decade, had a talisman quality. This was not merely because they determined the amount of federal money that would flow to the city. More importantly, they validated the citys seeming perpetual motion machine where growth not only appeared to pay for itself but also was a feedback loop of prosperity. More than 100,000 people arriving every year to the metropolitan area provided seemingly indisputable validation.

For a moment, even some hardened local skeptics had a difficult time denying the success. Americas largest cities were New York, Los Angeles, Chicago, Houston and now Phoenix. For members of the citys business and political elite, the moment carried a sense of inevitability. This was certainly the mood among a delegation of Phoenix leaders invited to the City of Brotherly Love, where they were greeted generously and with no small amount of envy. Phoenix was, the Philadelphians gushed, so new and clean, its government businesslike and efficient and the economic wind was at its back. None of the guests disagreed, for the essential characteristic of Phoenicians is optimism, where the future is always a rising path.

The reality was more complex. Indeed, the gathering economic bubble and Great Recession would shatter Phoenix, sending it into its worst times since the 1890s. But that was a couple years away and only a relatively few people saw it coming, much less dared to warn others about it.

Next page