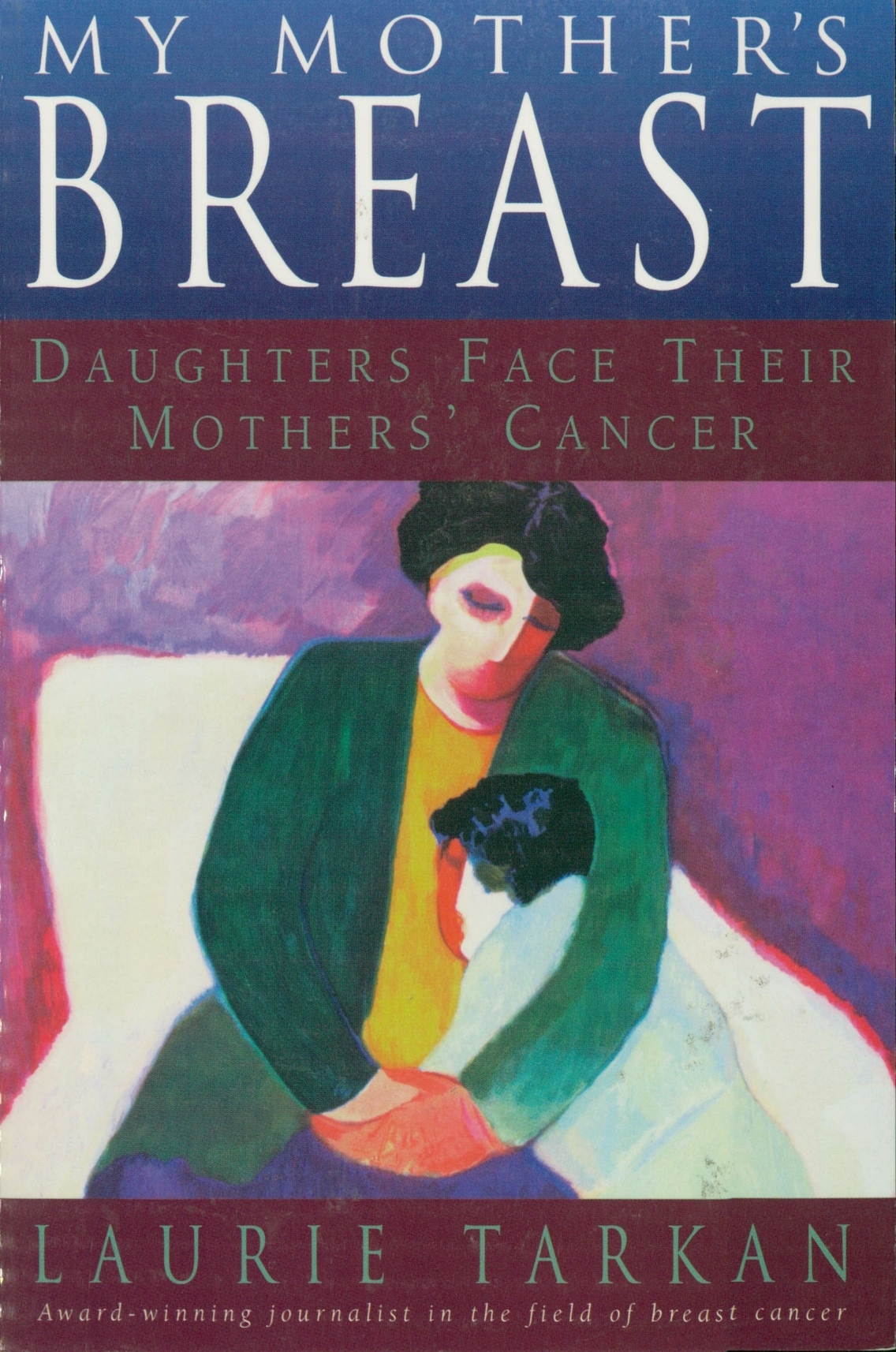

I am deeply grateful to the daughters and mothers who showed great courage in sharing their stories for this book. They spoke with honesty and candor and with the sole purpose and hope of helping other women who may find themselves venturing up this difficult trail after them. They are Caleen, Cynthia, Felicia, Jennifer, Jill, Judy, Julie, Karen, Kathie, Lauren, Lisa, Marcia, Mickey, Sandy, Stephanie, Sunshine, and Suzanne and others who chose to remain anonymous. I am also grateful to the many other daughters, sisters, and mothers who talked to me, whose stories I could not include, but whose thoughts and experiences are intricately woven into the fabric of the book.

My deepest thanks belong to my father, Stuart Tarkan, who, after the death of my mother, filled the roles of both mother and father for my sister and me. He is a generous and caring man, my oldest and best friend, who has encouraged me, consoled me, guided me, taught me, and most recently has endured my difficult questions about my mothers illness for this book. I also owe thanks to my husband, Andrew, whose love and support kept me going through this emotionally difficult endeavor.

This book would not exist without my agents: Connie Clausen was the first to understand my vision for the book, a vision that she sharpened with her insight and nourished with her encouragement. I was fortunate to have worked with her and known her before her sudden death in September 1997. I continued the project with her associate, Stedman Mays, whose warmth, enthusiasm, and humor have kept me inspired and confident through the writing process. From the beginning, my editor, Camille Cline, believed in the importance of this book and its contribution to filling the void for daughters. I am deeply grateful to her for helping me to achieve my vision.

Christine Many, my research assistant, worked after hours to help with the medical research. Lynn Ermann and Hilary Macht took time out of their own journalism schedule to read my early drafts, and offered insightful and creative feedback. My mentors, Lynne Cusack and Lorraine Daigneault, two brilliant and generous women, have guided me at different stages of my journalism career and have given me valuable advice on this book.

Im grateful to the following people who provided their expertise and knowledge on the subjects of mother-daughter relationships, living with sickness, death and dying, and breast cancer. They are Evelyn Bassoff, Barbara Bernhardt, Margaret Burke, Bruce Compas, Robert T. Croyle, Marguerite Eng, Sydney Ey, Sandra Haber, Hester Hill, Roberta Hufnagel, Christina Pozo Kaderman, Kathryn Kash, Caryn Lerman, Frances Marcus Lewis, Sue Miesfeldt, Julianne Oktay, June Peters, Adrienne Ressler, Gladys Rosenthal, Allison Ross, Pat Spicer, Jill Stopfer, David Wellisch, and the women at the Susan G. Komen Foundation, Cancer Care, Inc., and SHARE.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

American Cancer Society. Cancer and Genetics, Huntington, NY: PRI, 1997.

Baider, Lea, Cary L. Cooper, and Atara Kaplan De-Nour. Cancer and the Family. West Sussex, England: John Wiley & Sons, 1996.

Bassoff, Evelyn. Mothering Ourselves. New York: NAL-Dutton, 1992.

. Mothers and Daughters. New York: Plume, 1988.

Chernin, Kim. In My Mothers House. New York: HarperCollins, 1984.

Edelman, Hope. Motherless Daughters. New York: Addison-Wesley, 1994.

Feldman, Gayle. You Dont Have to Be Your Mother. New York: W. W. Norton, 1994.

Friday, Nancy. My Mother, My Self . New York: Dell, 1987.

Kaye, Ronnie. Spinning Straw into Gold. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1991.

Kelly, Patricia T. Understanding Breast Cancer Risk. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1991.

Lorde, Audre. The Cancer Journals. San Francisco: Aunt Lute Books, 1980.

Love, Susan. Dr. Susan Loves Breast Book. New York: Addison-Wesley, 1995.

Lowinsky, Naomi Ruth. The Motherline. Los Angeles: Tarcher, 1993.

. Stories from the Motherline. Los Angeles: Tarcher, 1992.

McCarthy, Peggy, and Jo An Loren, eds. Breast Cancer? Let Me Check My Schedule. Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 1997.

Moch, Susan Diemert. Breast Cancer: Twenty Womens Stories. New York: NLN, 1995.

National Cancer Institute. Taking Time: Support for People with Cancer and the People Who Care about Them. Bethesda, MD: NCI, 1997.

Offit, Kenneth. Clinical Cancer Genetics. New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1998.

Quindlen, Anna. One True Thing. New York: Bantam Doubleday Dell, 1997.

Pedersen, Lucille. Breast Cancer: A Family Survival Guide. Bergin & Garvey, 1995.

Phillips, Shelley. Beyond the Myths: Mother-Daughter Relationships in Psychology, History, Literature, and Everyday Life. London: Penguin, 1991.

Rich, Adrienne. Of Woman Born. New York: Norton, 1986.

Rollin, Betty. First You Cry. New York: Harper, 1976.

Royak-Schaler, Renee, and Beryl Lieff Benderly. Challenging the Breast Cancer Legacy. New York, HarperCollins, 1992.

Wadler, Joyce. My Breast. New York: Addison-Wesley, 1992.

Waldholz, Michael. Curing Cancer. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1997.

Weiss, Robert S. Learning from Strangers. New York: Free Press, 1994.

Williams, Terry Tempest. Refuge: An Unnatural History of Family and Place. New York: Vintage Books, 1992.

Wittman, Juliet. Breast Cancer Journal. Golden, CO: Fulcrum, 1993.

NOTES

p. 4 The statistics on breast cancer are from the American Cancer Society, Cancer Facts & Figures.

p. 4 daughters do tend to have more intrusive thoughts C. Lerman, K. Kash, M. Stefanek, Younger Women at Increased Risk for Breast Cancer: Perceived Risk, Psychological Well-being, and Surveillance Behavior, journal of the National Cancer Institute Monographs 1994, 16:171.

p. 4 Compass studies conclude E. K. Grant, B. E. Compas, Stress and Anxious-Depressed Symptoms Among Adolescents: Searching for Mechanisms of Risk, Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 1995, 63(6):1015.

p. 6 David Wellisch found that when a mother dies D. K. Wellisch, E. R. Gritz, W. Schain, et al., Psychological Functioning of Daughters of Breast Cancer Patients, (Part 1), Psychosomatics 1991, 32:324; (Part 2), Psychosomatics 1992, 33:171.

p. 26 Jungian book K. Carlson, In Her Image: The Unhealed Daughters Search for Her Mother, Boston & London: Shambhala, 1990.

p. 39 This increase in their responsibilities Grant & Compas, 1995.

p. 67 a study by Frances Marcus Lewis E. H. Zahlis, F. M. Lewis, The Mothers Story of the School-Age Childs Experience with the Mothers Breast Cancer, Journal of Psychosocial Oncology In press.

p. 139 according to a study of high-risk women Lerman, Kash, & Stefanek, 1994.

p. 141 Though estimates vary only 6 to 19 percent K. F. Hoskins, J. E. Stopfer, et al., Assessment and Counseling for Women with a Family History of Breast Cancer, Journal of the American Medical Association 1995, 273(7):577.

p. 142 women who had high levels of anxiety C. Lerman, E. Lustbader, et al., Effects of Individualized Breast Cancer Risk Counseling: A Randomized Trial, Journal of the National Cancer Institute 1995, 87(4):286.

p. 146 Stopfer and her coauthors divided women into two at-risk groups Hoskins, Stopfer, et al., 1995.

p. 151 Indeed, the American Cancer Society (ACS) Statement of the American Society of Human Genetics on genetic testing for breast and ovarian cancer predisposition, American Journal of Genetics 1994, 55:i.

p. 152 Studies show that when high-risk women are given the option C. Lerman, M. D. Schwartz, S. Narod, H. T. Lynch, The Influence of Psychological Distress on Use of Genetic Testing for Cancer Risk, Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 1997, 65(3):414.