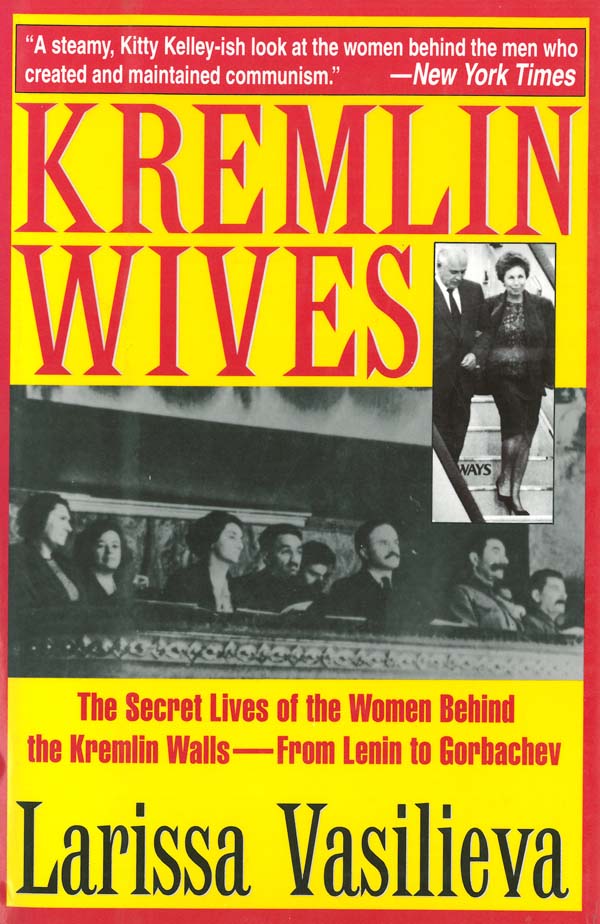

Copyright 1992, 2011 by Larissa Vasilieva

Translation copyright 1994, 2011 by Larissa Vasilieva and Cathy Porter

All Rights Reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without the express written consent of the publisher, except in the case of brief excerpts in critical reviews or articles. All inquiries should be addressed to Arcade Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018.

Arcade Publishing books may be purchased in bulk at special discounts for sales promotion, corporate gifts, fund-raising, or educational purposes. Special editions can also be created to specifications. For details, contact the Special Sales Department, Arcade Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018 or arcade@skyhorsepublishing.com .

Arcade Publishing is a registered trademark of Skyhorse Publishing, Inc., a Delaware corporation.

Excerpts from Commissar: The Life and Death of Lavrenty Pavlovich Beria by Thaddeus Wittlin, 1972 by Thaddeus Wittlin, reprinted by permission of Macmillan Publishing Company

Visit our website at www.arcadepub.com .

10 9 8 76 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available on file.

ISBN: 978-1-61145-514-4

Contents

List of Illustrations

| Nadezhda Krapskaya | 12 |

| Inessa Armand | 12 |

| Nadezhda Krapskaya and Lenin | 26 |

| Nadezhda Krapskaya and Lenin | 26 |

| Nadezhda Krapskaya | 26 |

| Larissa Reisner | 41 |

| Olga Davidovna Kameneva | 51 |

| Alexander Kamenev | 51 |

| Lev Kamenev and Galina Kravchenko | 51 |

| Nadezhda Alliluyeva and Vasily Stalin | 62 |

| Josif Stalin and Nadezhda Alliluyeva | 62 |

| Olga Stefanovna Mikhailova-Budyonnaya | 95 |

| Olga Stefanovna Mikhailova-Budyonnaya | 95 |

| Maria Vasilievna Budyonnaya | 95 |

| Maria Vasilievna Budyonnaya | 95 |

| Ekaterina Ivanovna Kalinina | 127 |

| Ekaterina Ivanovna Kalinina | 127 |

| Mikhail Ivanovich and Ekaterina Ivanovna Kalinin. | 127 |

| The Molotovs and the Stalins | 139 |

| Paulina Zhemchuzhina Molotov | 157 |

| Vyacheslav, Paulina Zhemchuzhina, and |

| Svetlana Molotov | 157 |

| Paulina Zhemchuzhina with her grandson | 157 |

| Nina Teimurazovna Beria | 166 |

| Tatyana Okunevskaya | 166 |

| Nikita Sergeyevich Khrushchev with his family | 199 |

| Nikita Khrushchev with Leonid Brezhnev and Anastas Mikoyan | 199 |

| Nikita Khrushchev, Anastas Mikoyan, and Kliment Voroshilov with their wives and children | 201 |

| International Womens Day, March 8 | 213 |

| Leonid and Victoria Brezhnev | 213 |

| Raisa and Mikhail Gorbachev | 231 |

| Raisa Gorbachev | 231 |

| Raisa Gorbachev | 231 |

Introduction

I F THE LIVES THE Soviet leaders led behind the Kremlin walls are still a subject of fascination and mystery, those of their wives remain a complete enigma. Throughout the seventy-five years of Soviet history little or nothing about these women was made public. Were they merely shadows of their sometimes terrifying husbands? I suspected not. In fact, I was sure they played a central role in the dramas that unfolded inside the Kremlin, and I became determined to uncover their stories. I wanted to discover who they were, how they spent their days, and what their relationships were, both to the men of power and to those around them.

A variety of sources were available to me. There were the scholarly volumes of memoirs and research published in Russia and abroad, but these works, predominately written by male authors, refer only fleetingly to the women of the Kremlin. I started, then, by reading all the available memoirs and biographies of Lenins wife, Nadezhda Krupskaya; of Inessa Armand, an important early Bolshevik as well as Lenins mistress; and of Alexandra Kollontai, another celebrated revolutionary. These books, however valuable, were official publications, generous on politics and dialectics, scant on the personal aspects of these womens lives. I also read a number of memoirs written by the wives of enemies of the people, tragic, disturbing and restrained.

There were, too, the hearsay, rumors, and legends that had been circulating over the years, which, though largely unsubstantiated, nevertheless provided useful leads.

A few of the Kremlin women who had survived their years behind the forbidding walls agreed to talk with me. Each new meeting set me the delicate task of addressing historical accuracy while not insulting the woman interviewed, and at the same time encouraging her to share her life story. Their accounts drew me on to meetings with relatives and friends of Kremlin women who had died. I have countless hours of interviews on tape. Each tells a fascinating story, and each has its predictable share of entangled half-truths. These interviews inevitably led me to other important sources: archives, manuscripts, documents, and letters.

Another point of access was through my own family connections and my life as a writer. As the daughter of the engineer who designed the now-famous World War II Soviet tank, the T-34, I was exposed at a young age to the elite circles of Soviet society. Later my name as a writer and supporter of womens rights eased my access to the people I interviewed and to the archives where I searched for insights into my subjects lives.

All these sources were invaluable. Ultimately, however, I realized that if I were to complete the project, I would have to gain access to the KGB files in the Lubyanka headquarters. In the spring of 1991, I asked the Writers Union to request on my behalf access to the files pertaining to the Russian wives arrested during the purges of the 1930s and 1940s. For months I heard nothing. Then, in August 1991, in the wake of the coup and three days after the statue of Felix Dzerzhinsky founder of the Cheka, a forerunner of the KGB had been toppled from its imposing pedestal on Lubyanka Square, my phone rang. It was an official from KGB headquarters. He informed me without ceremony that my request had been granted, but that I had to come immediately.

I reached Lubyanka Square and entered the infamous building that for so long had stuck terror into the hearts of so many. I was led upstairs to a large room overlooking the square, formerly the office of KGB chiefs Beria, Yagoda, Yezhov, and Andropov. Behind it was Dzerzhinskys old office. I sat down in a huge armchair set before a long, T-shaped table, facing a portrait of Lenin and a bust of Dzerzhinsky. Alone in the inquisitors office, I picked up the receiver of a telephone switchboard emblazoned with die emblem of the USSR. The line was dead. The office was completely cut off from the world. I eyed nervously the stack of files sitting there on the polished table. It seemed incredible that I was here of my own free will, knowing that when my allotted hours were up I could leave. I thought of all those who had come here and never left. My mind conjured up the image of the tortured, the sounds of doors clanking and keys grating in locks. I thought of the lives of the people whose files sat before me. And then, feverishly, I began to read. The women of the Kremlin came alive again in my mind. Some, whom I already knew through their memoirs and letters and through interviews with friends and foes, came into clearer focus. Others, whom I knew only vaguely or not at all, cast new light on my subject. Before that first visit to the KGB files was over, I knew I had found many of the missing pieces I needed to complete my project.