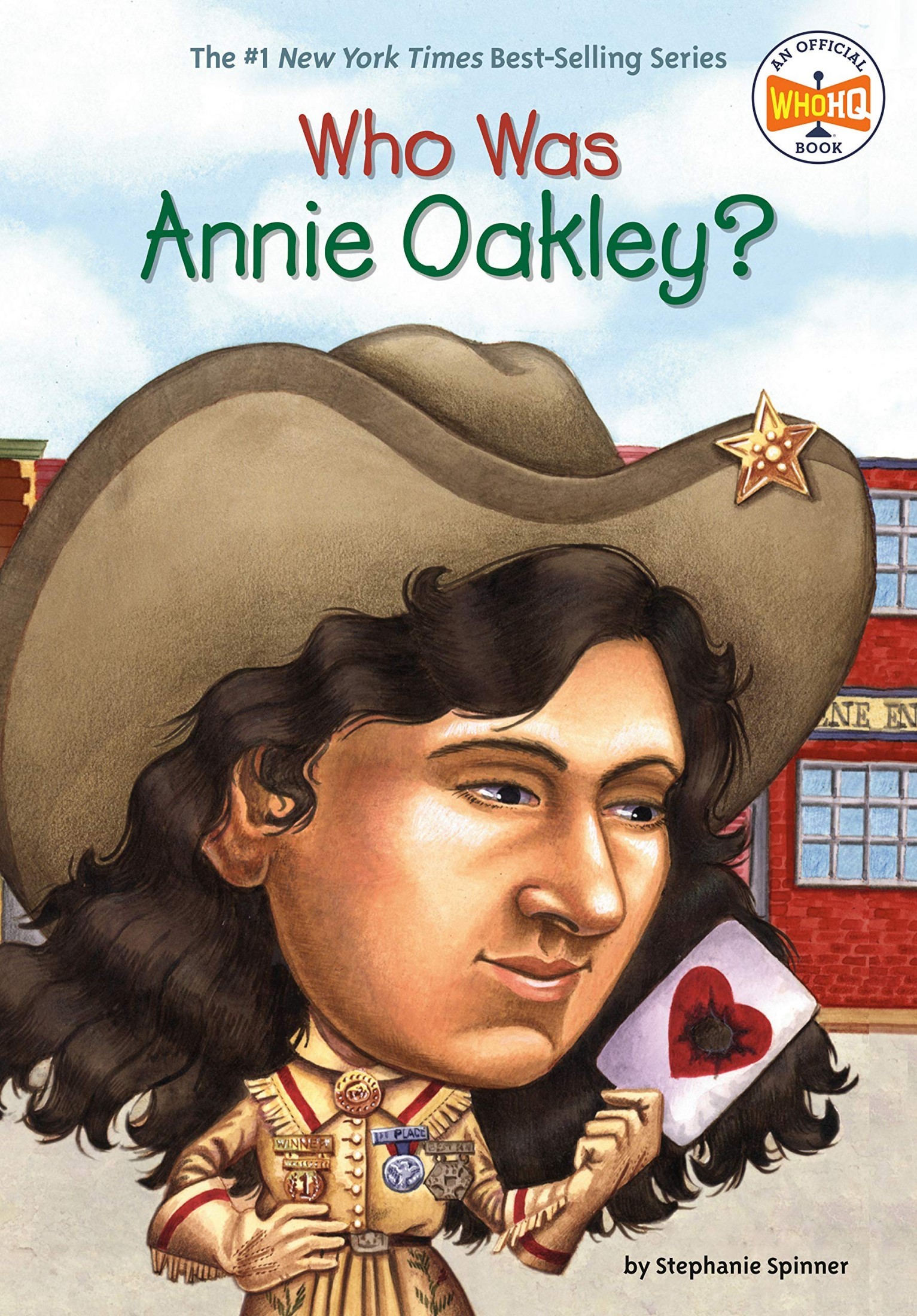

Who Was

Annie Oakley?

By Stephanie Spinner

Illustrated by Larry Day

Grosset & Dunlap New York

To Ariel ChapmanS.S.

Text copyright 2002 by Stephanie Spinner. Illustrations copyright 2002 by Larry Day. Cover illustration copyright 2002 by Nancy Harrison. All rights reserved. Published by Grosset & Dunlap, a division of Penguin Putnam Books for Young Readers, 345 Hudson St., New York, NY 10014. GROSSET & DUNLAP is a trademark of Penguin Putnam, Inc. Published simultaneously in Canada. Printed in the U.S.A.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

ISBN: 978-1-101-64006-7 20 19 18 17 16 15

Contents

Who Was

Annie Oakley?

Aim at a high mark, and youll hit it.

Annie Oakley

Who was Annie Oakley?

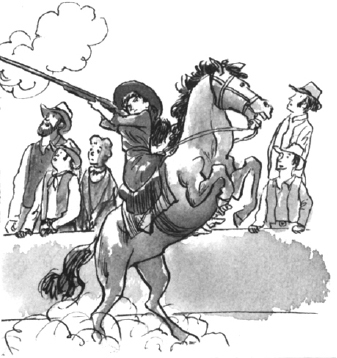

Her real name was Phoebe Ann Moses, and she ignored rules all her life. In an age when ladies did not handle guns, she became a sharp-shooting legend. While most women stayed at home with their children, she traveled the world performing for enormous crowds, living happily in a big canvas tent. She was quiet, even shy, yet a brilliant performer.

During her lifetime, 18601926, women were paid far less than men, but at her peak she earned as much as the President of the United States. She was one of the best-known women of her age, and the public loved her, yet she was never anything but modest and down-to-earth.

Her life story inspired books, movies, television shows, and Broadway musicals. Most important, it changed the image of American women forever.

Chapter 1

Darke County

Phoebe Ann Moses was born on August 13, 1860, in Darke County, Ohio. Her birthplacea rough settlers cabin built by her father, Jacobwas near the tiny village of Woodland. It was also close enough to the woods for good hunting. Even as a tiny girl, Annie loved to go hunting with her father.

Sadly, Jacob Moses died of pneumonia when Annie was five years old. He left her mother, Susan, with six young children to care for. Susan Moses was a hardworking country nurse. But her wages$1.25 a weekwere not nearly enough to feed and clothe the family. They were very poor.

Annie and her brother and sisters helped out as best they could. They cared for the animals, did the laundry, worked in the garden, baked and cooked and sewed, and looked after the babies. Somehow we managed to struggle along, Annie said of those times.

Annie always liked roaming in the woods. They were alive with squirrels, rabbits, chipmunks, turkeys, and pheasants. She began making trapscornstalks stacked up and tied with stringto catch wild birds. Her father had taught her how to make them, and she was good at it.

Her traps put food on the table every day. We served them toasted with dressing, fried, broiled, fricasseed, and in potpies, and sometimes they made a nourishing broth, Annie wrote of the birds she caught.

As welcome as the food was, Susan Moses found Annies hunting troubling. She wanted her daughter to be a lady, not a hunter. Moreover, Susan was a Quaker. She believed in living without harming others. She had forbidden Annie to touch Jacobs rifle, which hung over the fireplace.

Annie had never shot a gun. But she had watched her father many times. One day when she was alone, she climbed on a chair and took down the rifle. She knew she was disobeying her mother. She also knew her brothers and sisters were nearly sick with hunger.

Somehow Annie managed to load and fire the big old rifle, and to hit a squirrel. When she brought it home, Susan Moses was pleased to have food for the family. But she was also disturbed by Annies growing interest in guns. They might be necessary for survival, but they were dangerous. Susan Moses did not like them.

Annie felt differently. I guess the love of the gun must have been born in me, she said. By the time she was ten, she was handling her fathers rifle with ease.

Chapter 2

The Infirmary

In 1871, Annie was sent to work at the Darke County Infirmary. This was a poorhousea place for orphans and homeless poor people who couldnt take care of themselves.

Annie did housework in exchange for room and board. If she wanted to earn a little money, she could mend and sew.

Though she was not happy about living there, Annie understood why her mother had sent her away. Susan Moses was haunted by the fear that she could not provide for her children. Sending children to other households was a common practice at the time, a way to ensure that they would be cared for. Annies younger sister Hulda already was living with another family.

Things started off well enough at the infirmary. Annie learned to knit and embroider and use a sewing machine. Samuel and Nancy Edington, the couple in charge, liked the way Annie always pitched in and did her best. They praised her for it.

Unfortunately, their praise reached the wrong ears. One day a man came to the infirmary looking for household help. He heard the Edingtons speak highly of Annie. So he offered her fifty cents a week, plus time off for school and hunting. His wife, he said, needed a baby-sitter for their newborn child.