Sanjeev Shetty - No Middle Ground : Eubank, Benn, Watson and the Golden Era of British Boxing

Here you can read online Sanjeev Shetty - No Middle Ground : Eubank, Benn, Watson and the Golden Era of British Boxing full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2014, publisher: Aurum Press, genre: Non-fiction. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

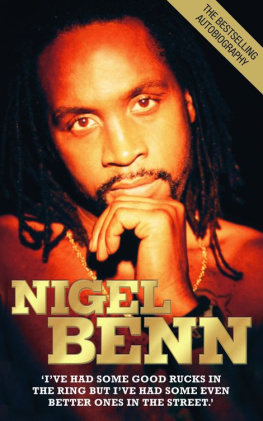

- Book:No Middle Ground : Eubank, Benn, Watson and the Golden Era of British Boxing

- Author:

- Publisher:Aurum Press

- Genre:

- Year:2014

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

No Middle Ground : Eubank, Benn, Watson and the Golden Era of British Boxing: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "No Middle Ground : Eubank, Benn, Watson and the Golden Era of British Boxing" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

No Middle Ground : Eubank, Benn, Watson and the Golden Era of British Boxing — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "No Middle Ground : Eubank, Benn, Watson and the Golden Era of British Boxing" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

SANJEEV SHETTY

GROUND

EUBANK, BENN, WATSON

AND THE LAST GOLDEN ERA OF BRITISH BOXING

For Mick Watts Ill keep writing them if you keep reading them

and

Richard Shepheard its not Sonny Liston, but I hope it will do.

I t seems the easiest thing in the world to say, but they didnt like each other.

If you were alive when Nigel Benn, Chris Eubank and Michael Watson attempted to settle things, youll know a bit about what it was like. And if you werent, then you have my sympathy. Because what we could not have realised then was how lucky we were. This was as good as it got and to quote my friend Glyn Leach, the editor of Boxing Monthly, theres been nothing to equal it since.

It began under a tent, on a Sunday night, in a deserted part of north London and the scale of it all was summed up by where it finished. At the home of the English football champions, Old Trafford, with over 40,000 people crammed into a venue nicknamed the Theatre of Dreams, the unlucky ones without tickets were forced to watch it on television. If Saturday night square-screen viewing defines us as a nation, with the masses now drawn to the finales of Strictly Come Dancing and its ilk, then what did it say about us twenty years ago when wed give up our evenings for blood, sweat and violence? Did we evolve, did boxing become less compelling or was it down to the quality of what was in front of us?

Im not sure there are any easy answers to the question. Except that, when it reached its height, on that otherwise tranquil evening in Manchester, I was there, part of a quartet of people from contrasting backgrounds and diverging futures, united by one thing. We all had our favourites. One day, wed all admit that if at times we wanted one of them to win more than the other, when it all came to an end, when the final punches had been thrown, admiring all three of them wasnt a chore.

A two-man rivalry is essentially a pick-em. Him I like, him I dont. When there are three, we look to find one who we can identify with. During the 1970s and early 1980s, one of sports most enduring rivalries could be found in tennis, with Bjrn Borg, John McEnroe and Jimmy Connors locked into something that all of us could relate to. Borg was the full vessel, or so it seemed, a man so at ease it seemed impossible to ruffle his feathers, even when others tried. Connors was the artisan, the blue-collar worker who played every week because hed known hard times and knew the value of every cent. And then there was McEnroe, the volatile, magical and charismatic kid who begged you to be seated even as he warmed up. Given his privileged background, no one could ever work out where the anger came from. But to see those eruptions was more than just a voyeuristic occasion. It was also a precursor to something that you knew would find its way into the scrapbooks.

While Borg, Connors and McEnroe were all-time greats, among the twenty best men ever to hold a racket, Benn, Eubank and Watson would probably only feature in the best-of category when the discussion turned to British boxers. However, the similarities were in how they felt about each other. There was dislike which quite often bordered on contempt. And these were young, angry men who had reached the ring by following different paths, but each of whom had a point to prove, and that made for a dangerous cocktail with a pair of ten-ounce gloves.

Chris Eubank looked imperious, his body seemingly carved from stone, his visage impassive and, whether by design or not, he dared his opponents to dislike him. Michael Watson had known hardship, raised with love but without luxury. He fought because it was something he was good at but also because he needed something other than faith and fresh air to live on. And then there was Nigel Benn, who could charm you outside the ring, but harm you inside it. The anger within was a mystery to those who didnt know him. Even after years as a professional boxer, he didnt know why hed wake up and want to hurt people.

Born within two and a half years of each other, all of West Indian immigrant parents, and raised in London, their rivalries did not begin in the amateur ranks. It was only when they started to earn money that the dislike came to the fore. When they started fighting for financial reward, Britain was a haven for quick-buck artists. And when one of them made easy money, the other two were left wondering why their pockets were empty. They all wanted to be champions, but also wanted to be paid more than the other. They all sought independence from the men who managed their careers. And they all thought they were the best. Most attempts to settle things in the ring provoked more arguments.

Their contests sometimes reached genuine sporting greatness and at other times promised more than they delivered. But the tension was always there. These were three men who, at various times, genuinely despised each other sometimes the hate appeared manufactured, but we didnt know that, nor did we know how much that personal venom would both shape and destroy them. All we knew was that it made for some of the most unforgettable boxing this country has ever played host to.

In their own way, theyd all pay a high price for their endeavours. History tells us that ring wars, when fuelled by personal animosity, can have tragic consequences. In 2013 we mourned the passing of Emile Griffith, a superlative boxer of the 1960s, who spent the last fifty years of his life in a state of torment because of one of boxings most gruesome moments. Griffith, a humble welterweight from the Virgin Islands, became a popular figure in his adopted New York because of his classic style and easy-going attitude. In 1962, his demeanour was disturbed when an opponent, Cuban Benny Paret, grabbed his buttocks before a bout and called him a maricn, the day before they were due to fight at Madison Square Garden. The word maricn is Spanish slang for homosexual, something that no man would admit to being then and even less so if he was a boxer. It was the kind of thing one man could say to another in the 1960s without fear of the authorities interceding. Fast forward fifty years and the British heavyweight Tyson Fury can expect a fine from those who run the sport in this country for making homophobic comments on his Twitter account. Times have changed for the better, with even boxing, as old-fashioned a sport as any, doing more than before to eradicate prejudice.

But back to the 1960s, being called a maricn provoked a fury in Griffith which had not been evident before, perhaps because he had been harbouring doubts about his sexuality that he would struggle to come to terms with throughout his life. If those who managed and trained him regretted their fighters lack of anger, they had no idea of the consequences once that fuse was lit. Paret and Griffith had fought twice before, the Cuban winning the second bout after being stopped in the first. If only in terms of combat there had been honour in those bouts, there would be no such thing in the third and final episode of their rivalry. Griffith had been told by his trainer, Gil Clancy, to keep throwing punches if he got Paret in trouble. And in round twelve thats exactly what he did. Paret, hurt in a corner of the ring, was subjected to an attack of unmistakable hostility and fury. More than twenty punches landed on his chin and upper body before he slumped to the canvas, unconscious. The images were captured live on American television and even the most optimistic viewer would have been able to tell that Parets life was in danger. The Cuban slipped into a coma from which he would never awake, dying nine days after taking his final punch. It was the first ring death ever recorded on live television and its memory still brings a shudder to those who saw it in the flesh or on celluloid. Boxing disappeared from television screens in America for ten years, so haunting were those final seconds of Parets life. In the course of Benn, Eubank and Watsons rivalry, there was a reminder of how close a boxers life comes to a premature end when the reason to fight becomes personal and not professional.

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «No Middle Ground : Eubank, Benn, Watson and the Golden Era of British Boxing»

Look at similar books to No Middle Ground : Eubank, Benn, Watson and the Golden Era of British Boxing. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book No Middle Ground : Eubank, Benn, Watson and the Golden Era of British Boxing and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.