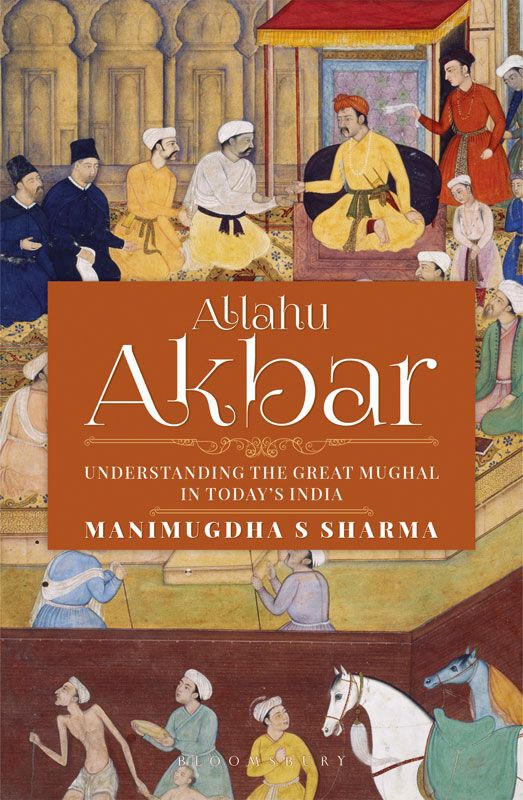

BLOOMSBURY INDIA

Bloomsbury Publishing India Pvt. Ltd

Second Floor, LSC Building No. 4, DDA Complex, Pocket C 6 & 7,

Vasant Kunj New Delhi 110070

BLOOMSBURY, BLOOMSBURY INDIA and the Diana logo are trademarks of

Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

First published in India 2019

This edition published in 2019

Copyright Manimugdha Sharma 2019

Illustration Manimugdha Sharma 2019

Manimugdha Sharma has asserted his right under the Indian Copyright Act to be identified as the Author of this work

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or any information storage or retrieval system, without the prior permission in writing from the publishers

Bloomsbury Publishing Plc does not have any control over, or responsibility for, any third-party websites referred to or in this book. All internet addresses given in this book were correct at the time of going to press. The author and publisher regret any inconvenience caused if addresses have changed or sites have ceased to exist, but can accept no responsibility for any such changes

ISBN: HB: 978-9-3869-5053-6; eBook: 978-9-3869-5054-3

2 4 6 8 10 9 7 5 3 1

Created by Manipal Digital

Bloomsbury Publishing Plc makes every effort to ensure that the papers used in the manufacture of our books are natural, recyclable products made from wood grown in well-managed forests. Our manufacturing processes conform to the environmental regulations of the country of origin

To find out more about our authors and books visit www.bloomsbury.com and sign up for our newsletters

O n 10 October 1941, one Adi K. Munshi of Bombay (now Mumbai) wrote a letter to the editor of The Times of India . That was the time of the Second World War, and there was unrest in India. There was a deep chasm between the Indian National Congress and the Muslim League following the Lahore Resolution that had envisaged independent states on the North-west and East of India, where there was a Muslim majority.

The resulting ill feeling had trickled down to the general populace as well. In hindsight, as we understand today, the ground was being prepared for the eventual Partition. But Munshi couldnt have possibly known or had any inkling of what lay ahead in the future. He wished for peace and communal amity, and he longed for a leader whom he thought could unite the Hindus and the Muslims. It was not Mohandas K. Gandhi, Muhammad Ali Jinnah or Jawaharlal Nehru. It was not Subhas Chandra Bose or Vallabhbhai Patel either. It was someone from the glorious past of India. It was Emperor Jalaluddin Muhammad Akbar.

When Munshi wrote that letter, he had the 400th birth anniversary of the emperor in mind, which he thought was on 14 October. However, the newspaper printed it a day later on 15 October, the actual birthday of Akbar. Munshi used phrases for the Mughal emperor that were quite illuminating about his perception among the Indians of that timelike great Indian soldier, statesman and the greatest Indian nationalist of all time.

To bolster his point, Munshi invoked the words of a great historian about AkbarWhen we reflect what he did, the age in which he did it, the method he introduced to accomplish it, we are bound to recognise in Akbar one of those illustrious men whom Providence sends, in the hour of a nations trouble, to reconduct it into those paths of peace and toleration which alone can assure the happiness of millions. That great historian was Colonel G. B. Malleson, who concluded his book Akbar and the Rise of the Mughal Empire (1896) with these profound words.

Munshi ended his short epistle with hope, which read almost like a prayer. In these days of domestic discord, communal dissensions and particularly the HinduMuslim split, India feels, more than ever, the need of an Akbarthe Apostle of united India.

Did Munshi have a premonition of the things to come? We dont know. But we know that the image of Akbar as a successful ruler who united multiple warring factions around his throne made him an ideal person to be emulated back then. What made Akbar unique was the fact that he had both physical and moral courage. Anyone who has either kind of courage always wins adulation. But those who are blessed with both not only win admiration but also hearts. Such people make leaders. Great leaders. Even heroes. Akbar was one such man.

In 2017, I was at a talk on the trial of Bhagat Singh by legal eagle A. G. Noorani at the Delhi Legislative Assembly. Noorani, while extolling the virtues of the young revolutionary, had briefly described the relationship between Singh and the then Punjab Congress stalwart, Lala Lajpat Rai. Noorani had said, and I had reported it for The Times of India :

He (Singh) parted ways with Lala Lajpat Rai when he became communal. But when Rai died after being hit by a police baton charge, Singh decided to avenge him, for he was still a man of principles. And he did.

Noorani was referring to the 1928 protest against the Simon Commission during which Rai had sustained fatal blows. Singh and his associates at the Hindustan Socialist Republican Association had responded to it by killing police deputy superintendent C. F. Saunders in Lahore, the city that had once been the capital of the Mughal Empire of Akbar.

The Indian Left often alludes to Rais communal image, and it is done not without reason. Rai was part of the Lal-Bal-Pal triumvirate (the other two being Bal Gangadhar Tilak and Bipin Chandra Pal) that not only led the Extremist faction of the Indian National Congress but also believed in Hindu nationalism.

In Indian Nationalism: The Essential Writings (2017), Syed Irfan Habib wrote about how Rai used his nationalism brush to segregate the medieval Hindus from the Muslims. Habib wrote that while both Daulat Khan Lodhi and Rana Sanga had invited Babur to invade India, to Rai, Lodhis act was one of opportunism while Sangas was of patriotism borne out of the wish to liberate his motherland. But for Akbar, Rai had made a rare exception, and he was willing to lock horns with those Englishmen who portrayed a less than flattering picture of Akbar.

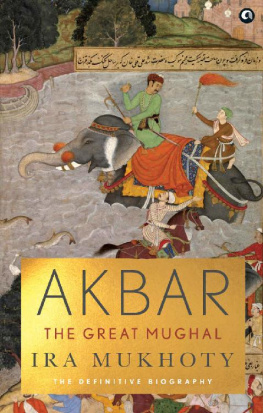

In 1918, Rai was in America as the First World War was ending. There, he had reviewed Sir Vincent Smiths biography of Akbar called Akbar the Great Mogul , 154265 , in the Political Science Quarterly . Rais first line in the review wasAkbar the Great Mogul was by common consent one of the greatest monarchs known to history.

Rai said, Mr. Smith has told the story of Akbars life and administration with great lucidity, thoroughness and general impartiality, but at places is unduly hard on him, forgetting the times in which he lived and worked. This was a very important criticism by Rai, something that holds true even today for everyone but especially for those new detractors of Akbar who bash him up on television studios and in the Twitter world without bothering to check if they are talking about a medieval Indian emperor or some 20th-century tinpot dictator.