Edith Sitwell - Taken Care Of: An Autobiography

Here you can read online Edith Sitwell - Taken Care Of: An Autobiography full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2011, publisher: A&C Black, genre: Non-fiction. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Taken Care Of: An Autobiography

- Author:

- Publisher:A&C Black

- Genre:

- Year:2011

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Taken Care Of: An Autobiography: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Taken Care Of: An Autobiography" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Taken Care Of: An Autobiography — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Taken Care Of: An Autobiography" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Edith Sitwell

An Autobiography

This book was written under considerable difficulty. I had not recovered from a very severe and lengthy illness, which began with pneumonia. The infection from this permeated my body, and the bad poisoning of one finger lasted for fifteen months. This was agonizingly painful, and I could only use either hand with great difficulty, as the poison spread gradually. The reminiscences in this book are of the past. I do not refer to any of my dearly-loved living friends. I trust that I have hurt nobody. It is true that, provoked beyond endurance by their insults, I have given Mr. Percy Wyndham Lewis and Mr. D. H. Lawrence some sharp slaps. I have pointed out, also, the depths to which the criticism of poetry has fallen, and the non-nutritive quality of the bun-tough whinings of certain little poetastersbut I have been careful, for instance, not to refer to the late Mr. Edwin Muir (Dr. Leaviss spiritual twin-sister). I have attacked nobody, unless they first attacked me. During the writing of certain chapters of this book, I realized that the public will believe anythingso long as it is not founded on truth.

| Dame Edith Sitwell died on December 9th, 1964, shortly after writing this preface. |

An Exceedingly Violent Child

Kierkegaard, in his Journals, wrote I am a Janus bifrons: I laugh with one face, I weep with the other.

*

In the following, but in no other way, do I resemble Savonarola, whose speech, though it related only to his home-town and not the universe, was, unknown to me, the forerunner of mine.

A lady asked me why, on most occasions, I wore black.

Are you in mourning?

Yes.

For whom are you in mourning?

For the world.

*

You were an exceedingly violent child, said my mother, without any animus.

The summer of the year 1887 had been particularly hot. One afternoon in the first week of September, my grandparents, Lord and Lady Londesborough, or rather, my grandmother (for my grandfather was a gentle creature whose motto seemed to be laissez-faire) seized upon my mothers bedroom in Wood End, our house in Scarborough, as the field of one of the worst battles that even my grandmother had ever engendered. These two shadowsone tall and extremely dark (I knew a German governess who thought, when she saw him riding in Hyde Park, that he must be the Spanish Ambassador), one, my grandmother, like an effigy of the Plantagenet race, her ancestorsan effigy into which Rage, her Pygmalion, had breathed lifestood with their backs turned towards the window of the huge conservatory, a background of large tropical leaves and plants, from which, at moments, great flowers like birds flew into my mothers room.

This floriation had a strong period atmosphere: silken cords, grey gauzes, green velvets, and crystal discs which blacken in the sun like gauze.

My grandmother stormed, bringing about my early arrival into the world by this singularly appalling row. My beautiful eighteen-year-old mother, bored by the storm (there can have been, apart from the wars in which nations were involved, nothing to equal it before, or after, the San Francisco earthquake) lay in bed awaiting my birth. I, on my part, occupied my unborn state with violent kickings and slappings against the walls of my prison, on the chance of my being let out. I did not know in what a world I was to find myselfin what a sicle inhumain.

I have wondered sometimes, my mother said, recalling this occasion, whether this violence was because you were trying to be born, or whether you were wanting to get at your grandmother.

A short way from the house, the sea crawled like a lion awaiting its prey, so softly you could not guess of what tremendous roars that seemingly gentle creature was capable across the lion-yellow sands.

My grandmothers rage seemed to fill the universe.

For some time she had been surprised by the immense showers of emeralds, rivalling the splendour of the Niagara Falls, which descended upon her from jewellers at the request of my grandfather.

It was only on the day to which I refer that she discovered that he was in the habit of visiting ladies whom one might describe as the naiads sheltering behind those showersnymphs who were occupied otherwise in prancing and squealing on the stage of musical comedies. After each of these visits, my grandfather was seized by remorsehence the emeralds.

My grandmother said everything that came into her head. But she kept the emeralds.

On the 7th September, two days after this battle, my grandfather, who was President of the Scarborough Cricket Festival, gave a huge luncheon party on the cricket ground, in a tent decorated by flowering plants in tubs, and by the black beards, the eyebrows like branches of winter fir-trees, of Dr. W. G. Grace and other cricketers.

All went well until it became obvious to the assembled company that I was about to make my entry into the world.

Narrowly escaping producing me on the cricket ground, my mother was rushed to Wood End, where, within the space of an hour or two, I was born.

I thought, once, that I remembered my birth. Perhaps what I remembered was my first experience of the light. In William Jamess Principles of Psychology he wrote The first time we see light, we are it rather than see it. But all our later knowledge is about what this experience gives: the first sensation an infant gets, is for him the universe.

That first sensation remains with every dedicated artist in all the arts. It has remained with me. The infant, William James continued, encounters an object in which all the categories of the understanding are contained. It has objectivity, causality, in the full sense in which any later object or system of objects have these things.

My parents understood nothing of what, from my childhood, was living in my head.

In an essay on an exhibition of Monsieur Massons paintings (translated by Madame Bussy and published in Transition Forty-Nine, Number 5) Monsieur Andr de Bouchet said while the painters art was becoming acuter, suns gave birth to innumerable other suns a fierce sun vibrating over cock-fights, a butterfly sun vibrating over the painters head, a bread sun behind the baker kneading her dough. All this I saw, transmuted from the painters vision into the poets. In a way, I had a wild beasts senses, a painters eyesight. Artists in all the arts should have the eyes, the nose, of the Lion, the Lions acuity of sense, and, with these, what Monsieur Andr Breton called

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

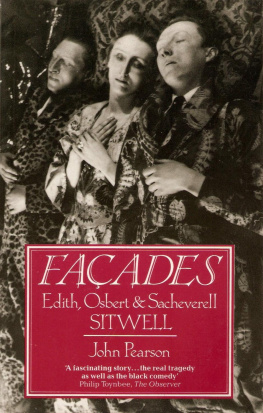

Similar books «Taken Care Of: An Autobiography»

Look at similar books to Taken Care Of: An Autobiography. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Taken Care Of: An Autobiography and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.