Contents

Joseph Ratzinger as a schoolboy in 1933 at Aschau am Inn, his fathers last family home. ( picture-alliance/dpa/dpaweb) |

The Ratzinger family in the mid-1930s. ( KNA Copyright 1938, KNA) |

The former police station and family home in Marktl am Inn, in which Benedict was born. ( picture-alliance/dpa/Sven Hoppe) |

The family in 1932 with grandparents in the Bavarian Forest, at the parental home. ( Archiv Nussbaum) |

The young Ratzingers in 1930. ( Archiv Walter) |

The three Ratzinger children in 1937 in Traunstein. ( Archiv Walter) |

The farm building in the village of Hufschlag near Traunstein, acquired by Ratzingers father after Hitler seized power. ( picture-alliance/dpa/Peter Kneffel) |

The future Pope in uniform, Munich, 1943. ( Getty Images/AFP) |

Joseph Ratzinger in 1958 as Assistant Professor of Philosophical Theology at the High School in Freisung. ( KNA-Bild/KNA) |

Ratzinger is ordained priest on June 29th 1951 in Freisung Cathedral by Cardinal Michael von Faulhaber. ( picture-alliance/dpa/lby/Erzbistum Mnchen-Freising) |

Ratzinger as a newly ordained priest with his brother Georg and friend Rupert Berger ( Stadtarchiv Traunstein/Oswald Kettenberger) |

Family photo in July 1951 at Traunstein. ( ddp/SIPA USA) |

Ratzinger as chaplain in 1951 outside the Munich presbytery of the Church of the Holy Blood. ( Archiv Pfarrei Heilig Blut, Mnchen) |

Mass in the mountains of the Chiemgauer Alps, Autumn 1952. ( KNA-Bild/KNA) |

Solemn Mass at St Peters in Rome during the Second Vatican Council. ( epd-bild/ Agenzia Romano Siciliani) |

Joseph Ratzinger as Professor at the University of Bonn. ( picture-alliance/Privat dpa/lby) |

Ratzinger with Cardinal Josef Frings of Cologne, at the opening of the Second Vatican Council. ( picture-alliance/dpa/dpaweb) |

Ratzinger with his sister Maria at the garden gate of Bergstrasse 6, Pentling. ( Horst Hanske) |

It was a cold, wet day in November 1992 when I had my first date with Joseph Ratzinger. It was about a profile of him for the Sddeutsche Zeitung magazine. I was surprised by how openly the Grand Inquisitor talked to me.

During the following years I have put at least two thousand questions to the cardinal, the pope, the pope emeritus, perhaps even more. He only hesitated to answer the very last ones. He said an answer would inevitably interfere with the present popes matters. I ought and want to avoid anything in that direction.

No, Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI has never become a parallel pope or even an antipope. On the contrary, he is scrupulously careful not to get in his successors way. But he has never taken a vow of silence. His last words in Castel Gandolfo as a reigning pope stressed that: From 8 p.m. I will no longer be pope, no longer the supreme pastor of the Catholic Church But with all my heart, my love, my prayers, my thoughts and all my intellectual powers I should like to go on working for the general good, the good of the church and humanity.

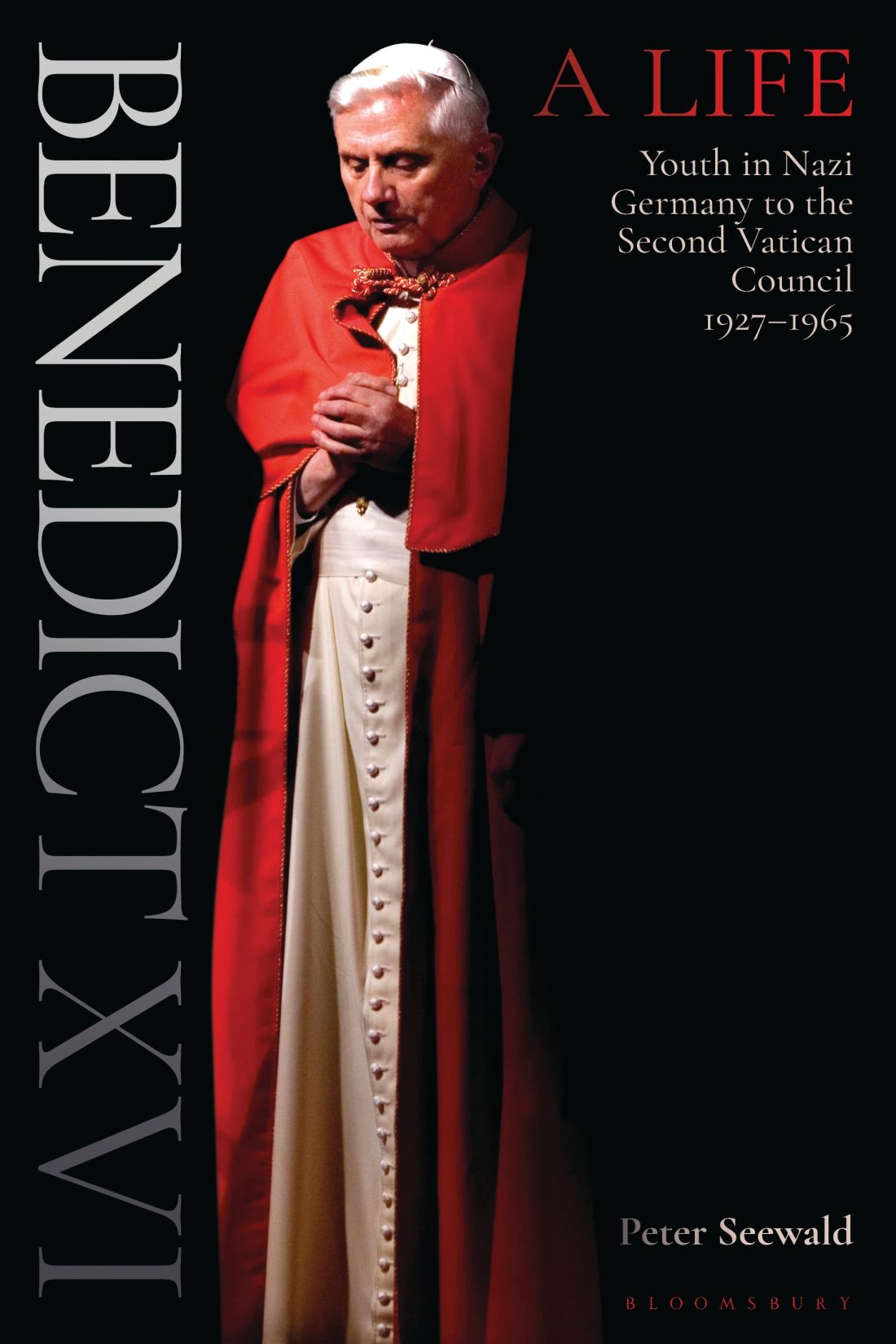

What a journey! A boy from a Bavarian village on the edge of the Alps becomes the supreme head of the oldest, greatest and most mysterious institution in the world, the Catholic Church, with its 1.3 billion members. He was the first German for 500 years to sit on the chair of St Peter. He was a theologian whose ecclesiastical and academic work was already important. Joseph Ratzinger has written history. As the Vatican Council greenhorn, as a renewer of theology, as a prefect who, side by side with Karol Wojtya, kept the ship of the church on course through the storm of that time. He is also the first reigning pope to resign from the office on grounds of age. There has never been a pope emeritus. Never before has a single person changed the papacy from one day to the next so much as he has.

The world is deeply divided about how to understand Benedict XVI. He is regarded as one of the cleverest thinkers of our time. At the same time he has remained a controversial figure. An uncomfortable one who exasperates his opponents. The French philosopher Bernard-Henri Lvy remarked that, as soon as Ratzingers name came up, prejudices, falseness and even plain disinformation ruled any discussion. The Austrian media expert Dr Friederike Glavanovics reported in an academic research paper that, with Joseph Ratzinger, many journalists tended compulsively to embed negative news into an even more negative context. An image has been constructed that is shaped not by reality but only by viability. It was a fictional picture meant to serve a particular purpose.

Who really is this man? What is his message? Was there actually a 1968 trauma that changed him from a progressive theologian into a reactionary? Was he the Panzer Cardinal he was made out to be? Did he keep silent and hush up the abuse scandal? Was his papacy an unparalleled failure, as his opponents never tire of maintaining? Benedict XVI: A Life searches for clues about the provenance, personality and the dramatic ups and downs in the life of the German pope. By putting the pieces back together for example, in the Williamson and the Vatileaks affairs it comes to some surprising conclusions. It was important to maintain a critical distance but also to look without prejudice. Otherwise, genuine understanding is not possible.

No book can be written without help, especially not a biography covering nearly a century, from the end of the Weimar Republic to the digital age. My thanks go to the approximately one hundred contemporary witnesses who were available for interview. I also want to thank all the colleagues and friends who have accompanied me in this work with advice and assistance and with their prayers, especially the popes brother, Georg Ratzinger, for details about the family history and Dr Manuel Schlgl, who talked to people who knew Ratzinger and was willing to read through the manuscript. Tanja Pilger brilliantly made excerpts from mountains of books and other materials. Id like to thank Martina Wendl and my son Jakob for transcribing the recordings. I thank my wife and my family for their comforting support, especially shown at those times when the author despaired over the volume of material and his own insufficiency.

I owe thanks to Archbishop Georg Gnswein for supporting the project from the beginning and for his impressive frankness. My special thanks, though, go to Pope Benedict. Over the years he himself has answered the most abstruse questions with angelic patience. He is surely the only reigning pope who left messages on an answering machine, as he did for my sons. I especially remember the summer of 2012. I was visiting the pope in Castel Gandolfo. He was in a terrible state. He seemed not only exhausted but also strangely depressed. I only realised afterwards that during those weeks he was struggling with the decision that would change the papacy for ever.

As pope of a new epoch, Benedict XVI was both the end of the old and also the beginning of something new, a bridge between two worlds. He showed that religion and reason were not contraries. That reason was in fact the guarantee needed to protect religion from sliding into wild fantasies and fanaticism. He charmed people with his generous nature, his great spirit, the honesty of his analysis and the depth and beauty of his words. With him everyone knew that what he proclaimed, however uncomfortable it might be, was dependably in accord with the teaching of the gospel, continuity with the church fathers and the reforms of the Second Vatican Council. It went with the advice not just to fiddle about with externals but to take a deep look at the nature of things, at what life and faith actually are. We may not agree with all his positions. But there is no doubt that Joseph Ratzinger can be called not only an important academic but perhaps the greatest theologian ever to sit on the chair of St Peter. He was also a spiritual master who convinced through his uprightness and genuineness. His direction was not outdated: quite the contrary. As his successor put it: A great pope, great for the power and penetration of his intelligence; great for his important contribution to theology; great for his love of the church and human beings. And finally, great for his virtues and faith.