Table of Contents

For Joe

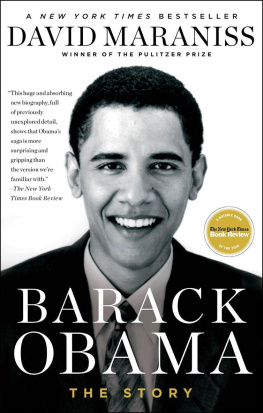

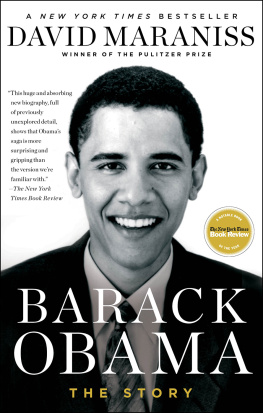

I think sometimes that had I known she would not survive her illness, I might have written a different bookless a meditation on the absent parent, more a celebration of the one who was the single constant in my life.

BARACK OBAMA, Dreams from My Father,

preface to the 2004 edition

Prologue

I am the son of a black man from Kenya and a white woman from Kansas.

BARACK OBAMA, MARCH 18, 2008

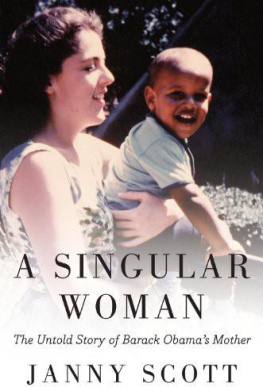

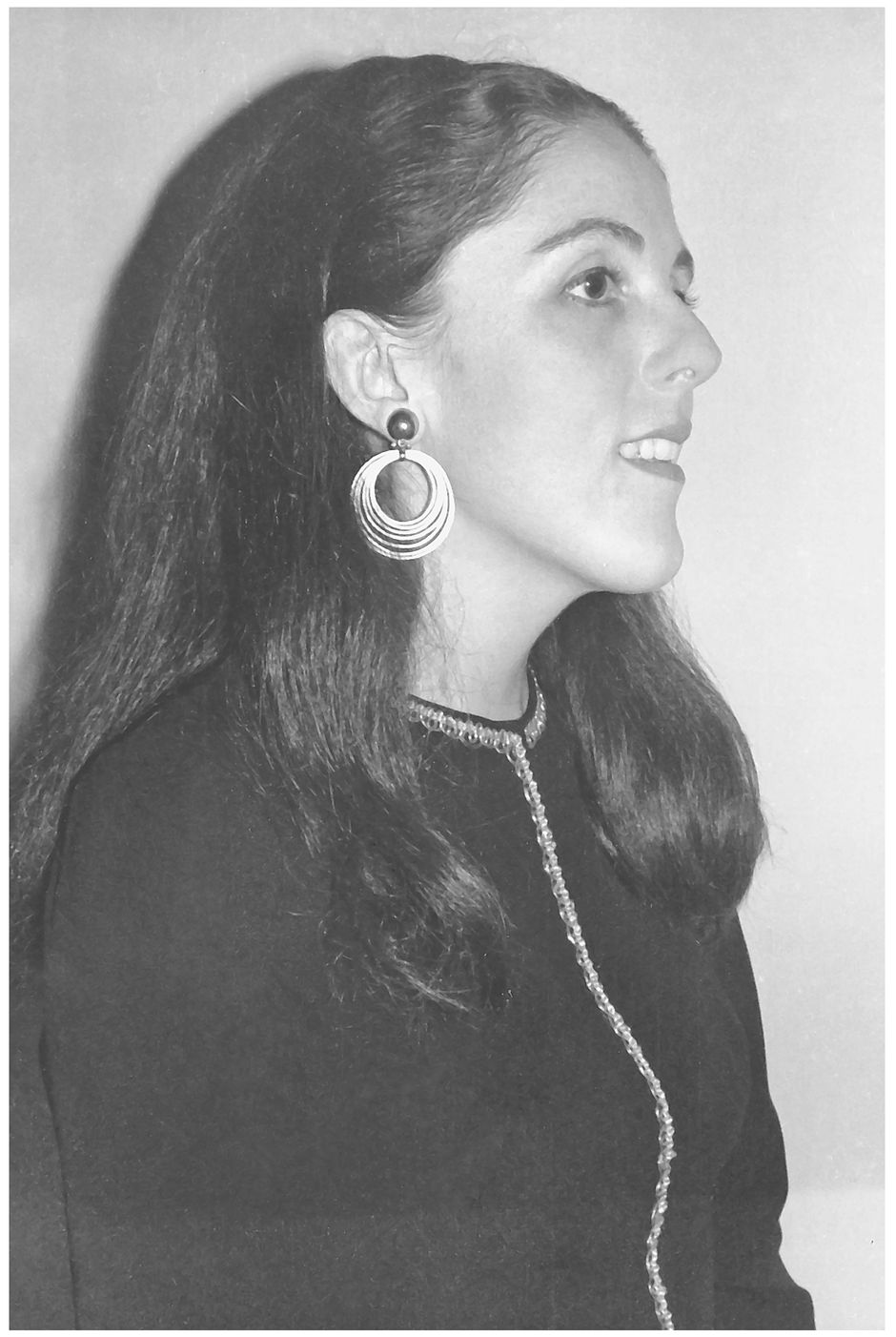

The photograph showed the son, but my eye gravitated toward the mother. That first glimpse was surprisingthe stout, pale-skinned woman in sturdy sandals, standing squarely a half-step ahead of the lithe, darker-skinned figure to her left. His elastic-band body bespoke discipline, even asceticism. Her form was well padded, territory ceded long ago to the pleasures of appetite and the forces of anatomical destiny. He had the studied casualness of a catalog model, in khakis, at home in the viewfinder. She met the camera head-on, dressed in hand-loomed textile dyed the color of indigo, a silver earring half hidden in the cascading curtain of her dark hair. She carried her chin a few degrees higher than most. His right hand rested on her shoulder, lightly. The photograph, taken on a Manhattan rooftop in August 1987 and e-mailed to me twenty years later, was a revelation and a puzzle. The man was Barack Obama at age twenty-six, the community organizer from Chicago on a visit to New York. The woman was Stanley Ann Dunham, his mother. It was impossible not to be struck forcefully by the similarities, and the dissimilarities, between them. It was impossible not to question, in that moment, the stereotype to which she had been expediently reduced: the white woman from Kansas.

The presidents mother has served as any of a number of useful oversimplifications. In the capsule version of Obamas life story, she is the white mother from Kansas coupled alliteratively with the black father from Kenya. She is corn-fed, white-bread, whatever Kenya is not. In Dreams from My Father, the memoir that helped power Obamas political ascent, she is the shy, small-town girl who falls head over heels for the brilliant, charismatic African who steals the show. In the next chapter, she is the naive idealist, the innocent abroad. In Obamas presidential campaign, she was the struggling single mother, the food stamp recipient, the victim of a health-care system gone awry, pleading with her insurance company for coverage as her life slipped away. And in the fevered imaginings of supermarket tabloids and the Internet, she is the atheist, the Marxist, the flower child, the mother who abandoned her son or duped the state of Hawaii into issuing a birth certificate for her Kenyan-born baby, on the off chance that he might want to be president someday.

The earthy figure in the photograph did not fit any of those.

A few months after receiving the photo, I wrote an article for The New York Times about Dunham. It was one in a series of biographical articles on then Senator Obama that the Times published during the presidential campaign. It was long for a newspaper but short for a life, yet people who read it were seized by her story and, some said, moved to tears. As a result of the article, I was offered a chance to write a book on Dunham, and I spent two and a half years following her trail. I drove across the Flint Hills of Kansas to the former oil boomtowns where her parents grew up during the Depression. I spent many weeks in Hawaii, where she became pregnant at seventeen, married at eighteen, divorced and remarried at twenty-two. I traveled twice to Indonesia, where she brought her son, at six, and from whence she sent him back, alone, at age ten, to her parents in Hawaii. I visited dusty villages in Java where, as a young anthropologist, she did fieldwork for her Ph.D. dissertation on peasant blacksmithing. I met with bankers in glass towers in Jakarta where, nearly two decades before Muhammad Yunus and Grameen Bank shared the Nobel Peace Prize for their work with microcredit, Dunham worked on the largest self-sustaining commercial microfinance program in the world. I combed through tattered field notebooks, boxes of personal and professional papers, letters to friends, photo albums, the archives of the Ford Foundation in Midtown Manhattan, and the thousand-page thesis that took Dunham fifteen years to complete. I interviewed nearly two hundred colleagues, friends, professors, employers, acquaintances, and relatives, including her two children. Without their generosity, I could not have written this book.

To describe Dunham as a white woman from Kansas is about as illuminating as describing her son as a politician who likes golf. Intentionally or not, the label obscures an extraordinary storyof a girl with a boys name who grew up in the years before the civil rights movement, the womens movement, the Vietnam War, and the Pill; who married an African at a time when nearly two dozen states still had laws against interracial marriage; who, at age twenty-four, moved to Jakarta with her son in the waning days of an anti-communist bloodbath in which hundreds of thousands of Indonesians are believed to have been slaughtered; who lived more than half of her adult life in a place barely known to most Americans, in an ancient and complex culture, in a country with the largest Muslim population in the world; who spent years working in villages where an unmarried, Western woman was a rarity; who immersed herself in the study of a sacred craft long practiced exclusively by men; who, as a working and mostly single mother, brought up two biracial children; who adored her children and believed her son in particular had the potential to be great; who raised him to be, as he has put it jokingly, a combination of Albert Einstein, Mahatma Gandhi, and Harry Belafonte, then died at fifty-two, never knowing who or what he would become.

Had she lived, Dunham would have been sixty-six years old on January 20, 2009, when Barack Obama was sworn in as the forty-fourth president of the United States.

Dunham was a private person with depths not easily fathomed. In a conversation in the Oval Office in July 2010, President Obama described her to me as both naively idealistic and sophisticated and smart. She was deadly serious about her work, he said, yet had a sweetness and generosity of spirit that resulted occasionally in her being taken to the cleaners. She had an unusual openness, it seems, that was both intellectual and emotional. At the foundation of her strength was her ability to be moved, her daughter, Maya Soetoro-Ng, once told me. Yet she was tough and funny. Moved to tears by the suffering of strangers, she could be steely in motivating her children. She wept in movie theaters but could detonate a wisecrack so finely targeted that no one in earshot ever forgot. She devoted years of her life to helping poor people, many of them women, get access to credit, but she mismanaged her own money, borrowed repeatedly from her banker mother, and fell deeply in debt. In big and small ways, she lived bravely. Yet she feared doctors, possibly to her detriment. She was afraid of riding the New York City subway system, and she never learned to drive. At the height of her career, colleagues remember Dunham as an almost regal presencedecked out in batik and silver, descending upon Javanese villages with an entourage of younger Indonesian bankers; formidably knowledgeable about Indonesian textiles, archaeology, the mystical symbolism of the wavy-bladed Javanese kris; bearing a black bag stuffed with field notebooks and a Thermos of black coffee; a connoisseur of delicacies such as tempeh and