Manabi Devi - An Educated Woman In Prostitution

Here you can read online Manabi Devi - An Educated Woman In Prostitution full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2021, publisher: S&S India, genre: Non-fiction. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

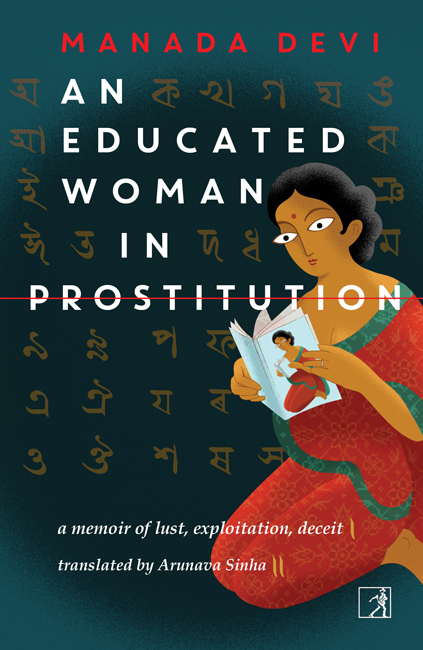

- Book:An Educated Woman In Prostitution

- Author:

- Publisher:S&S India

- Genre:

- Year:2021

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

An Educated Woman In Prostitution: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "An Educated Woman In Prostitution" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

An Educated Woman In Prostitution — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "An Educated Woman In Prostitution" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

An Educated Woman

in Prostitution

A Memoir of Lust, Exploitation, Deceit

(Calcutta, 1929)

MANADA DEVI

Translated from the Bengali by Arunava Sinha

Chapter the First

In Childhood

I WAS BORN ON THE 18th of Ashadh in the year 1307 (1900 on the Gregorian calendar). My father was a Brahmin man from a respectable family, and I was his first child. I am unable to disclose his name and family background, for many of his offspring, close relatives and other members of the extended family are alive. Their social standing is not insignificant, and this memoir might come into their possession. I have no desire to disconcert them.

My grandfather was a householder of considerable means, with four town houses in Calcutta and a house with a large garden in the suburbs. When of advancing years, he retired from the service of His Majestys Government. My father was a lawyer at the Calcutta High Court, where his practice became successful rapidly, even requiring him to travel from time to time.

He had married when studying for his law degree, when my grandfather was still alive. My mothers family resided in Calcutta too; they were not particularly wealthy, but my grandfather was eager to have my mother as his daughter-in-law because of her high birth and exquisite beauty. He died two years after my birthit is only in my memory now that the pleasure of being held in his arms remains.

I was not neglected because I was a girl. Some of my fathers friends would say, A daughter as the first child is a harbinger of fortune. Although they said it in jest, there appeared to be some truth in it; my father had established his legal practice a few months before my birth, and it flourished by the day. It wasnt long before he had purchased a small zamindari with an annual income of 10,000 rupees at an auction.

I was sickly during my childhood, making my mother perpetually anxious. My grandfather spent unstintingly on my health; I have been told he was gazing at me on his deathbed, even at the very moment when he died. Today I feel this saintly man passed on his last breath to me, enabling me to survive every time I have been on the brink of death myself.

When I was three years old, I was afflicted by a complicated fever that led all the well-known doctors of the city, allopathic and ayurvedic, to give up on me. All my sense organs had ceased functioning. But the great physician, the late Dwarakanath Sen, proved especially adept at treating me.

My mother prayed to the god Shiva daily. One day, overcome by distress, she fell unconscious on the floor of her prayer-room. When she regained consciousness, she said, Khukumoni will recover, there is nothing to worry about anymore. I do not know whether she received a reassurance from the god she cherished in her heart, but it was true that thereafter I began to heal without the intervention of medicines. I regained my health once again in the space of four months.

There was one specific reaction to her fervour, however; my body began to wax like the moon in a cloudless sky. Family and neighbours alike expressed their surprise as my form filled out, my face glowed, my hair grew thicker and longer, and my demeanour became more joyful. In the past I was quiet and restrained; but after my illness I turned energetic. I would ask my mother for money to buy biscuits and lozenges and run to the stationery shop at the corner, or I would run about on our wide terrace to catch drifting kitesI had no fear of falling. Sometimes I would accompany our household maids to their homes, my mischiefs would exasperate the servants. I was prone to entering my fathers drawing room and creating a commotion. With no other children at home, I was the only one whose shouts and laughter would echo across the entire house. But I was embarrassed when my father recounted these incidents from my childhood.

Taking a bath was one of my greatest pleasures. At my mothers request, my father had had a large tank constructed for me in the courtyard, with a beautiful fountain spouting water in the middle. I had learnt how to swim at the age of six or seven; before going in for a bath I would fetch all the children of my age in the neighbourhood. We would play for hours in the water, shouting and laughing with joy. My mothers indulgence kept my father from scolding me.

There was one more habit I had developedof going out for a ride in the motor car every afternoon. When my father could not accompany me, my mother did. A cousin of mine from my mothers sidehis name was Nandalal, I called him Nanda-dadaused to live at our house so that he could study in a nearby school. Sometimes I would take a walk with him. The sight of the beautifully decorated shops on either side of the road, the trams, the chains of electric lights, the crowds of passers-by, all gave me unsurpassed joy. Even as a young girl I was a frequent visitor to the Alipore Zoo, the museum at Chowringhee, the Howrah Bridge, the gardens of Pareshnath, and the temple at Kalighat.

I was more inclined towards having birds at home than playing with dolls. My father would get me all manner of beautiful birds; among them were pigeons, mynahs, parrots, cockatoos, nightingales and magpies. I was neither fond of dogs or cats, nor attracted to flowers. As I grew older, however, my fascination with birds lessened.

My mother died while giving birth to a stillborn second child. I was ten years old, and the year was 1910. I was aware of what death meant; no one could delude me with falsehoods or console me. I threw myself on the floor, crying uncontrollably. My father picked me up in his arms, but I thrashed about like a lamb being taken to the slaughter and climbed down. The neighbours bedecked by mothers dead body with flowers and took her away; I ran after them. I recall stumbling and falling face down on the pavement after a short distance. Looking up, I discovered the bearers of the body receding in the distance; all that remained in my vision were the soles of my mothers feet, the edges lined with red altaa, peeping out at the bottom of the cot on which she had been laid.

My tears know no bounds today as I write of my tragic life. All the tears that I have shed all these years have, it seems to me, gathered at my mothers feet to moisten the dried lines of red on them and make them fresh again.

My father had wept copiously at my mothers demise, refusing to eat for three days before giving in to his friends collective requests. A giant bromide enlargement of my mothers photograph in sepia tones used to hang on my fathers walls; he had given it to me as a gift on my seventh birthday. He had spent seven hundred and fifty rupees on having it made in England. He would put a garland of fresh flowers on it every day now, after my mothers death.

I had joined Bethune School while my mother was still alive: I was a student in the sixth class when she died. A private tutor used to teach Nanda-dada and me at home. But my father withdrew me from school after my mothers death, and appointed a reputed teacher to be in charge of my education. Perhaps he had made these arrangements so as to keep me near him in an effort to mitigate his own suffering. In any event, this change did no harm to my education.

Six months passed. The swadeshi movement in Bengal was followed immediately afterwards by a spate of bomb attacks by revolutionaries. Exile for the leaders, gaol for the young men, arrests for the revolutionaries, death sentences for those caught with bombsall of these created a furore. There were meetings and gatherings everywhere, gymnasiums were set up to train the youth in stick-to-stick combat. My father was involved with the revolutionaries; sometimes Nanda-dada used to take me to the meetings demanding independence, where I would hear fiery speeches being made.

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «An Educated Woman In Prostitution»

Look at similar books to An Educated Woman In Prostitution. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book An Educated Woman In Prostitution and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.