Contents

Guide

An Imprint of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

1230 Avenue of the Americas

New York, NY 10020

www.SimonandSchuster.com

Copyright 2021 by Simon Welfare

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof in any form whatsoever. For information, address Atria Books Subsidiary Rights Department, 1230 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10020.

First Atria Books hardcover edition February 2021

and colophon are trademarks of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

and colophon are trademarks of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

For information about special discounts for bulk purchases, please contact Simon & Schuster Special Sales at 1-866-506-1949 or .

The Simon & Schuster Speakers Bureau can bring authors to your live event. For more information or to book an event, contact the Simon & Schuster Speakers Bureau at 1-866-248-3049 or visit our website at www.simonspeakers.com.

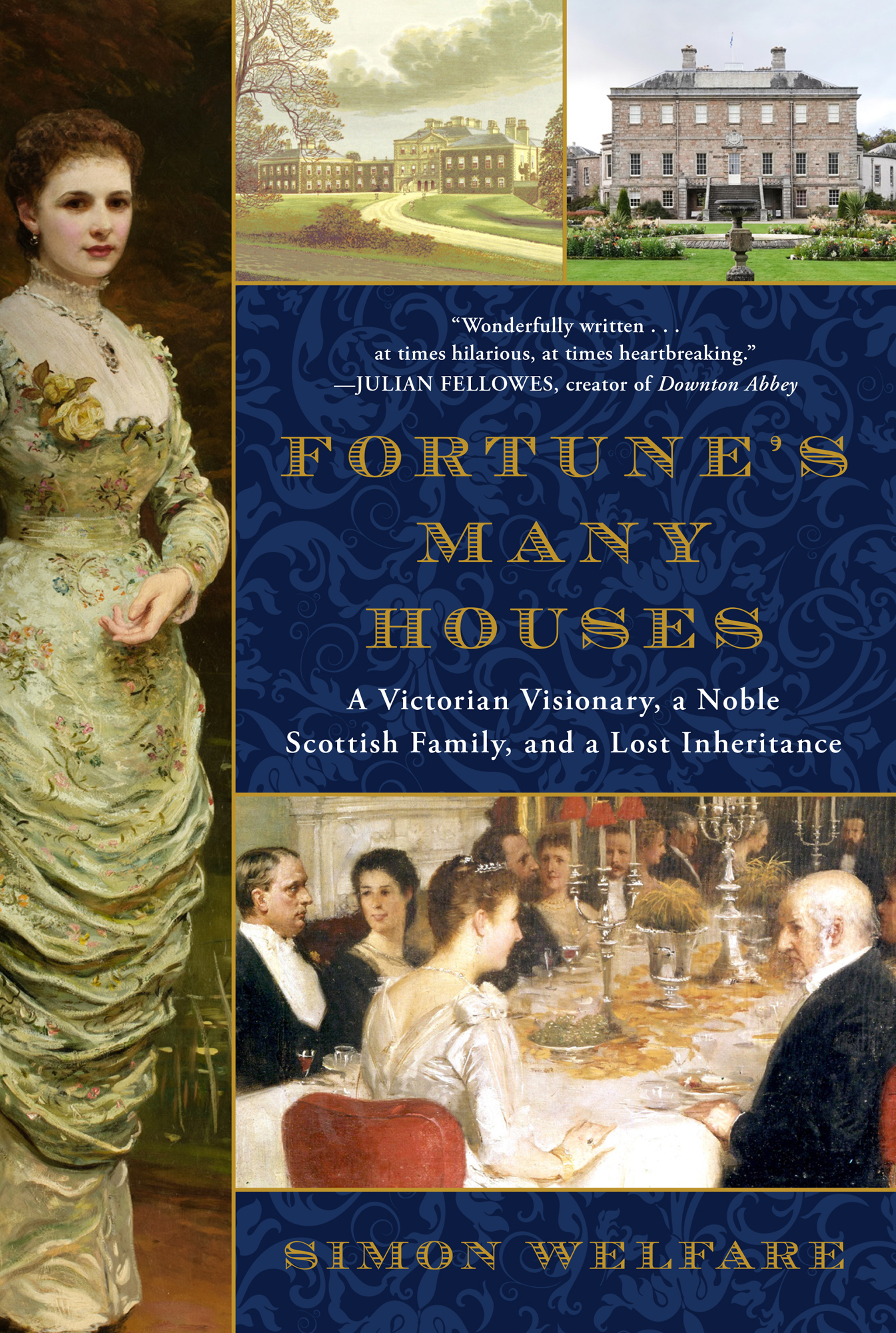

Interior design by Kyoko Watanabe

Jacket Paintings of Haddo House by Private Collection Mark Fiennes Archive/Bridgeman Images; Antiqua Print Gallery/Alamy Stock Photo; Smith Archive/Alamy Stock Photo; Ishbel Painting by Countess of Aberdeen Courtesy of National Trust For Scotland, Haddo House; Photographs of Haddo House Marlene Lee and Alan Oliver/Alamy Stock Photo

Author photograph by Anke Addy

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Welfare, Simon, author.

Title: Fortunes many houses : a Victorian visionary, a noble Scottish family, and a lost inheritance / Simon Welfare.

Description: New York : Atria Books, [2021] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2020042155 (print) | LCCN 2020042156 (ebook) | ISBN 9781982128623 (hardcover) | ISBN 9781982128647 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Aberdeen and Temair, Ishbel Gordon, Marchioness of, 18571939. | Aberdeen and Temair, Ishbel Gordon, Marchioness of, 18571939Homes and haunts. | Aberdeen and Temair, John Campbell Hamilton-Gordon, Marquess of, 18471934. | Aberdeen and Temair, John Campbell Hamilton-Gordon, Marquess of, 18471934Homes and haunts. | Social reformersGreat BritainBiography. | PoliticiansGreat BritainBiography. | Governors generalCanadaBiography. | ViceroysIrelandBiography. | Politicians spousesGreat BritainBiography. | Governors generals spousesCanadaBiography. | Viceroys spousesIrelandBiography.

Classification: LCC DA565.A145 W45 2021 (print) | LCC DA565.A145 (ebook) | DDC 941.1081092 [B]dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020042155

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020042156

ISBN 978-1-9821-2862-3

ISBN 978-1-9821-2864-7 (ebook)

For Joanna

and in memory of

Alexander

I believe that a biography is more effectual than any other kind of literature in turning the mind into a new channel, and causing it to take an interest in the concerns of others rather than its own.

GEORGE HAMILTON-GORDON , 5TH EARL OF ABERDEEN

Despite her preoccupation with many charities and her way of turning night into day, there was, there is, something extraordinarily comfortable about Lady Aberdeen. She, too, is of the women who make home wherever they are.

KATHARINE TYNAN , IRISH WRITER

Not long ago, I had occasion to undertake various repairs and alterations in a house. Having once entered upon the work, I followed it up with some energy, and each renovation seemed to bring to light the need of some further remedial work. But I soon found that these operations were subject to unfavourable criticism. Some said, This is a work of destruction; others, He has shifted that roofing and hell not be able to get it up again; others, These workmen are a great nuisance, raising such a noise and dusttheres no peace; and some would perhaps say or hint that It did well enough for your predecessors; why not leave things alone? To all this I paid very little attention; and what was the end of it? Why, everybody eventually admitted that a great and much needed improvement had been effected.

JOHN CAMPBELL GORDON , 7TH EARL OF ABERDEEN SPEECH TO THE ABERDEEN JUNIOR LIBERAL ASSOCIATION JANUARY 11, 1883

T HE D OOR O PENS

A House on a Hill, a House in a Valley

N ow, so long after, we disagree about what brought us one winters day to a ruin on a hillside in North Eastern Scotland.

Mary is certain that we were simply hunting for a new home, but I am not so sure.

I think that we were tugged there by a long thread of family history. The odd thing is that we succumbed willingly, even with enthusiasm, although we knew that, less than a century before, building another house amidst these beguiling hills had brought financial disaster to the great Scottish family to which Mary, my wife, belongs.

What we found that first afternoon was a U-shaped barnthe Scots call it a steadingbuilt of reddish granite, roofed with slates. The western end appeared to be in good repair. The farm machinery parked there was dry, though thick with bird droppings. The shafts of old carts had been stored across the beams: a few straddled them still. We climbed a ladder propped against the edge of a hayloft. Upstairs, in a dark chamber, in front of a small window, we found a wooden barrel. Whatever it had contained had leaked onto the flaking floorboards, forming a thick, sticky, orange puddle.

Back on the ground, we walked through the central cattle shed in the gathering gloom. The floor was still covered with straw and muck; the doors of the stalls flapped open or lay on the ground where they must have fallen when their hinges finally came away from the rotting pine posts, and part of the roof had collapsed. Slates, beams, and rubble barred the way to a smaller steading at the far end of the U. Its roof had sagged into a bow so deep and perfect that it looked as though it had been designed to cradle the wintry sky.

The remains of a cattle court lay in front. An abandoned car and a long iron tank lying on its side completed the picture of neglect and desolation.

Behind the steading, we could make out the crumbling concrete walls of a silage pit. Beyond it, a single willow tree perched on a knoll, a miniature version of the long, looming hill behind.

Just nearby, on the western side of the U, stood a small farmhouse, once home to the cowman, but now, we realized, in the early stages of gentrification.

But it was the view that made us both catch our breath: a vista of snow-dusted hills at the edge of a wide valley. High on the upper slopes, we could just make out flocks of sheep stoically cropping the grass beneath the crags. Below us, in the village, although it was barely three oclock, lights were already shining at the onset of what the locals call early dark.

The barn was too large for us: we had decided that as soon as we set foot in it. We were middle-aged; our children had left home; we knew that the house we had built on the other side of the county twenty years before, with its five acres of garden and as many bedrooms, was already too much to cope with. And yet

We knew, too, that building here would be expensive, perhaps ruinously so. That was what an earlier generation had learned so painfully, after starting with high hopes, heady with the view and the prospect of life among these hills. And yet

and colophon are trademarks of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

and colophon are trademarks of Simon & Schuster, Inc.