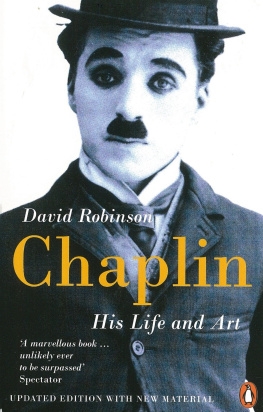

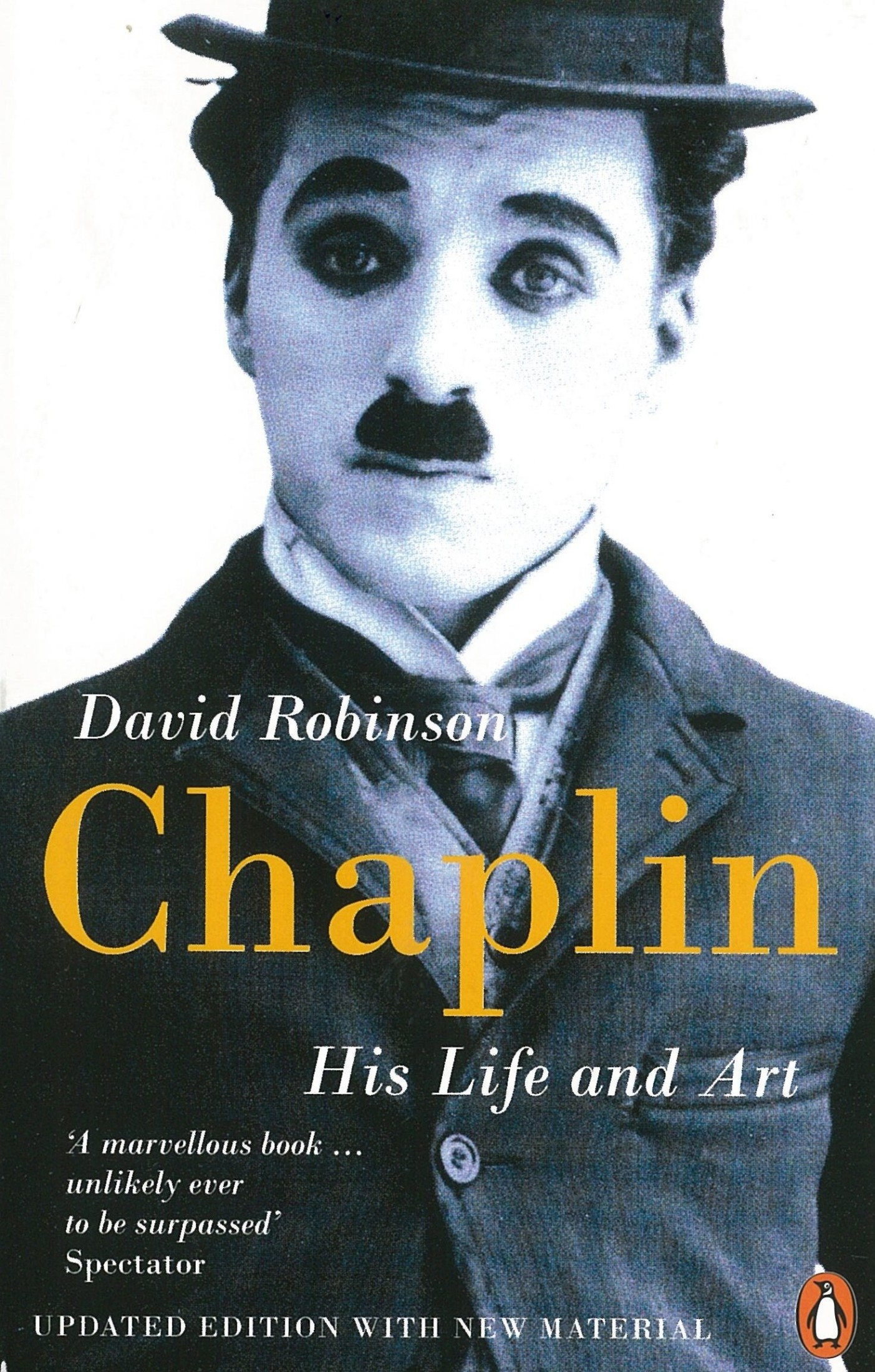

David Robinson - Chaplin: His Life and Art

Here you can read online David Robinson - Chaplin: His Life and Art full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2014, publisher: Penguin UK, genre: Non-fiction. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Chaplin: His Life and Art

- Author:

- Publisher:Penguin UK

- Genre:

- Year:2014

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Chaplin: His Life and Art: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Chaplin: His Life and Art" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Chaplin: His Life and Art — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Chaplin: His Life and Art" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

PENGUIN BOOKS

David Robinson is a film critic and historian, specializing in the archaeology of the cinema and the silent film era. He is currently Director of Le Giornate del Cinema Muto (the Pordenone Silent Film Festival) and was previously Director of the Edinburgh International Film Festival. Mr Robinson was for many years film critic for, successively, the Financial Times and The Times. His private collection of pre-cinema apparatus has been featured in exhibitions throughout Europe. Other books include Buster Keaton, The Great Funnies, Hollywood in the Twenties, World Cinema and Peepshow to Palace.

All photographs unless otherwise specifically acknowledged are the copyright of the Roy Export Company Establishment.

This started out, eighteen years ago, as a long book, and is now even longer. For an author who cherishes brevity, this is a matter of concern; but in Chaplins case discursiveness seems justified. An artist of universal stature has left uniquely and against all his intentions an extensive, detailed record of the life and the working processes that resulted in his creation. It would, then, seem irresponsible to curtail this record, or to shirk the opportunity to make it available to future researchers.

Since the book first appeared, new information has come to light, new recollections have been published, and old errors and misunderstandings have been exposed. This edition includes, for instance, fresh information on Hetty Kelly and on Chaplins 1925 fling with the legendary Louise Brooks; and the FBI records which only became available as the original edition went to press are now examined in more detail and incorporated into the body of the book. The smaller additions and amendments are too numerous to mention. The filmography has been improved in the light of recent research. New pictures have become available. The numerous friends who have contributed to extended knowledge of Chaplin are thanked in the Acknowledgements.

An unexpected source of insight into Chaplin and his times was the opportunity to work on Richard Attenboroughs biographical film, Chaplin, which was in part based on this book. The extraordinary dedication of Attenborough and his designer Stuart Craig to recreating the physical world in which Chaplins films were made offered many revelations. The accuracy of their effort was attested when William James who, as Little Billy Jacobs, had been the child star of Keystone in 1913, the year before Chaplin arrived there visited the set of Mack Sennetts studio which, in the absence of documentary evidence, Craig had reinvented. It is just as I remember it! Mr James exclaimed. It is given to a few people to have their memories realized.

I hope that in its own way the new edition of this book is the realization of Chaplins own memories of creation; and that readers will enjoy sharing them.

David Robinson

Bath, July 2001

The world is not composed of heroes and villains, but of men and women with all the passions that God has given them.

The ignorant condemn, but the wise pity.

Charles Chaplin, prefatory title to A Woman of Paris, 1923

Those big shoes are buttoned with 50,000,000 eyes.

Gene Morgan, Chicago newsman, 1915

Charles Chaplins autobiography appeared in 1964. He was then seventy-five years old. The book ran to more than five hundred pages and represented a prodigious feat of memory, for it was in large part done without reference to documentary sources. At the time, indeed, the feat seemed too prodigious to some reviewers, who were incredulous that anyone could remember in such detail events that had taken place a long lifetime before.

Since Chaplins death, I have had the privilege of examining the great mass of his working papers some of them unseen for more than half a century. In the public archives of London and in old theatrical records I have been able to uncover many long-forgotten traces of the young Chaplin and his family. In addition, a number of people in England and America have generously shared their memories and papers.

Sifting the mass of documentation has only served to heighten regard for the powers of Chaplins memory and the honesty of his record. An instance of the kind of detail which is constantly corroborated by the archives is the recollection, from his thirteenth year, that when his brother first went to sea he sent home thirty-five shillings from his pay packet: Sydney Chaplins seamans papers which were not available to Chaplin when he wrote exactly confirm the sum. Even small inaccuracies attest to his memory rather than discredit it. He remembers a childhood ogre, one of his schoolmasters, as Captain Hindrum, an old vaudeville friend of his mothers as Dashing Eva Lestocq and the friendly stage manager at the Duke of Yorks Theatre as Mr Postant. In fact their names turn out to have been Hindom, Dashing Eva Lester and William Postance. Chaplin probably never saw any of the names written down, and no doubt he recalled them simply as he heard them as a child. In themselves, the slips clearly show that Chaplins record is the result of a phenomenal memory rather than the product of post facto research and reconstruction. So regularly is his memory vindicated by other evidence that, where there are discrepancies without proof one way or the other, the benefit of the doubt often seems best given to Chaplin.

The present volume, originally written twenty years after Chaplins own account of his life, serves in part to complement My Autobiography. Subsequent research makes it possible to add further documentation and detail to the subjects sometimes random recollections. In their study Chaplin: Genesis of a Clown, Raoul Sobel and David Francis complained of the lack of hard facts and dates in the early chapters of My Autobiography. To try to keep a running time scale while reading My Autobiography is rather like having to navigate by the stars on an overcast night. By the time one reaches the next break in the clouds, the boat may be miles off course. This is true, perhaps: the special charm of those first chapters of My Autobiography is the free range of memory, unrestrained by the cold collaboration of any ghostly researcher. It is hardly to be wondered at if, at six or seven years old, the infant Chaplin was a trifle confused about the order of the workhouses and charity schools into which he was thrust. The importance of the autobiography is that it recorded his feelings in the face of these misadventures. The present volume can, at the risk of pedantry, tidy up the facts and chronology.

While My Autobiography is a strikingly truthful record of things witnessed, Chaplin might sometimes have been misled in the case of things reported to him. Like any mother, Mrs Chaplin must have tried to shield her children from unpleasant facts when she was able to do so. Some critics of the autobiography doubted whether Chaplins childhood could really have been as awful as he described. New discoveries suggest that Mrs Chaplin kept the worst from her children. The Chaplin boys seem never to have known, for example, of the sad fate of their maternal grandmother as she declined into alcoholism and vagrancy. Charles always believed that this grandmother was a gypsy, whereas the gypsy blood came with his paternal grandmother. Again, it was a natural misunderstanding for a child. Grandma Chaplin died years before his birth. Told that his grandmother was a gypsy, he could only assume it to mean the grandmother he had known.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Chaplin: His Life and Art»

Look at similar books to Chaplin: His Life and Art. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Chaplin: His Life and Art and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.