Table of Contents

Also by David Sears

The Last Epic Naval Battle:

Voices from Keyte Gulf

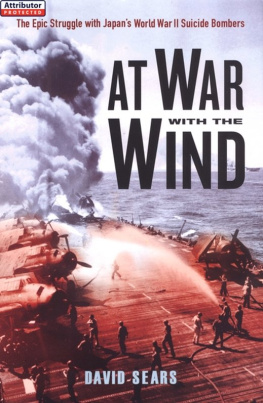

At War with the Wind: The Epic Struggle

with Japans World War II Suicide Bombers

For Virgil A. Stiger

USN and USMC veteran, best man,

and dearly missed friend

FOREWORD

Adm. James L. Holloway III, USN (Ret.)

Although Korea was a war America neither expected nor planned to fight, it had little choice. At dawn on June 25, 1950, when the North Korean Army without warning or provocation stormed across the South Korean border, their purpose was clearto annex the Republic of Korea, a free and sovereign nation, to the Communist North.

How would America and its free-world allies respond to this transparent Communist aggression? The choices seemed painfully dia - metric. Counter with diplomatic protests and ambiguous threats, thus risking its influence in the postwar world? Or unleash its arsenal of tactical atomic weapons, possibly triggering a full-scale nuclear war with the Soviet Union?

Instead, as the world watched apprehensively, America took the only option consistent with its national character: Draw a line in the sand, and, despite the extreme sacrifices that lay ahead, go to war with conventional arms.

America was totally unprepared for even a limited war. By early 1950 its massive armies, air forces, and seagoing fleets, so essential to allied victory in World War II, had been dismantled. For their part, Americans had little appetite for war, especially on a piece of the globe so remote and forbidding. As then Secretary of State Dean Acheson put it, If the best minds in the world had set out to find us the worst possible location to fight a war, the unanimous choice would have been Korea.

Rebounding from a disastrous start during which American and allied forces, acting under United Nations mandate, were nearly driven off the Korean peninsula, Americans mobilized and fought back with characteristic determination. After routing the North Korean Army, they ultimately drove Chinese armies out of South Korea, restored the original borders, and concluded an acceptable truce. The Korean War ended just as it began, along the 38th Parallel.

But the three-year conflict, which embroiled twenty-two belligerent nations and took the lives of over four million men, women, and children, left painful scars, both physical and emotional. For years it was a little considered footnote in historythe forgotten war. Today, however, fully six decades from its bloody beginning, the Korean War can be seen in a broader perspective: At a pivotal point in history, America and its free and like-minded allies stood firm and turned back totalitarian aggression. The contrasting circumstances of democratic South Korea and totalitarian North Korea speak volumes. Korea may well be the forgotten win.

While air power alone could not have won the Korean War, it nevertheless played a crucial role in shaping the final outcome. By the Chinese Armys own admission, UN air power was the equalizer to its vast numerical superiority in ground forces.

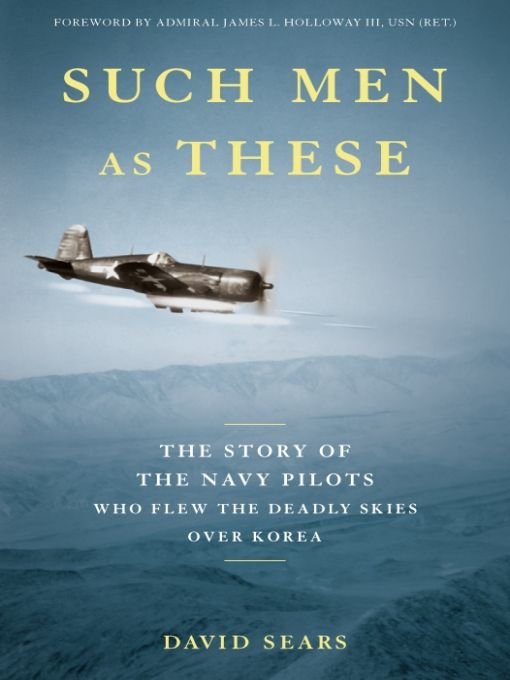

To fight its part in the air war over Korea, the U.S. Navy had to move quickly to reactivate its mothballed fleets of World War II warships and aircraft. The Navys active fleet carrier force grew to nineteen; propeller-powered F4U Corsairs, which had once dueled Japanese Zeroes over the Pacific, again flew from Navy carriers. A total of twenty-one carriers of all types ultimately served in the conflict, and carrier-based aircraft flew more than 30 percent of all UN combat sorties.

The Korean War ultimately restored the preeminence of the aircraft carrier task group in the U.S. fleet. But this resurgence would not have been possible had the Navy been unable to adapt these ships to handle jet aircraft. When jet squadrons were first deployed aboard the fleet carriers after World War II, the results were discouraging and often costly in losses of planes and pilots. But Naval Aviation pursued these programs aggressively and determinedly, finally overcoming seemingly insurmountable technical and operational obstacles. (It was during this time that, as a young naval aviator, I made my own professional transition from props to jets.) By the time Essex class carriers were deployed regularly to combat operations in Korea in the fall of 1950, all pilots and aircraft were mission-capable.

In 1953, during the closing days of the Korean conflict, Pulitzer Prize-winning author James Michener published The Bridges at Toko-Ri. Bridges is perhaps the best novelistic depiction of aerial combat and the skills, emotions, and personal trials of carrier-based combat pilots. During two Korean War deployments I personally experienced both the trepidation and exhilaration of twice-daily launches from carrier decks (often over tossing and frigid seas) and going feet dry to take out Communist targets ashore. Ironically, after the war, I was also privileged to fly as a stunt pilot in filming the movie version of The Bridges at Toko-Ri.

In the pages that follow, David Sears has looked behind the scenes to tell, compellingly and convincingly, the true stories of the U.S. Navy carrier pilots who braved the deadly wartime skies over Korea.

PROLOGUE: MARINERS

February 8, 1952, in the Sea of Japan East of North Korea

If a ships lineage best conveyed Americas dilemma in this war, this place, and this bitter season, it was USS Valley Forge (CV-45). Named for the bivouac site of Americas Continental army during the bleak Pennsylvania winter of 1777-1778, the 33,000-ton aircraft carrier had been built in Philadelphia during the closing days of World War II, her construction financed in part by the states citizens through a special war bond drive.

Valley Forge was launched in November 1945 but not finally commissioned until the following yeara proud, if somewhat belated, symbol of U.S. sea powers global supremacy. Soon, however, with the war over and the decade waning, Valley Forge, her dozens of Essex-class predecessors, and the handful of even larger Midway-class carriers that followed were widely criticized as huge, costly exemplars of the U.S. Navys obsolescence. The era of seagoing supremacy that large fleet carriers definedwhen flattops projected global power and airplanes, not ships, won blue-water battles and controlled vital sea-lanesseemed to be passing before it had much begun.

The atom bombthe device that had simultaneously closed the war with Japan and threatened unprecedented global apocalypsepointed to a new mind-set in military preparedness. If mastery of its secrets proliferated and deterrence failed, then war would be quick, decisiveand nuclear. Nuclear wars delivery system would not be flattop-based aircraft. Rather, it would be flights of land-based long-range, thermonuclear-armed strategic bombers, the specialty of the nations newest military branch, the United States Air Force (USAF).