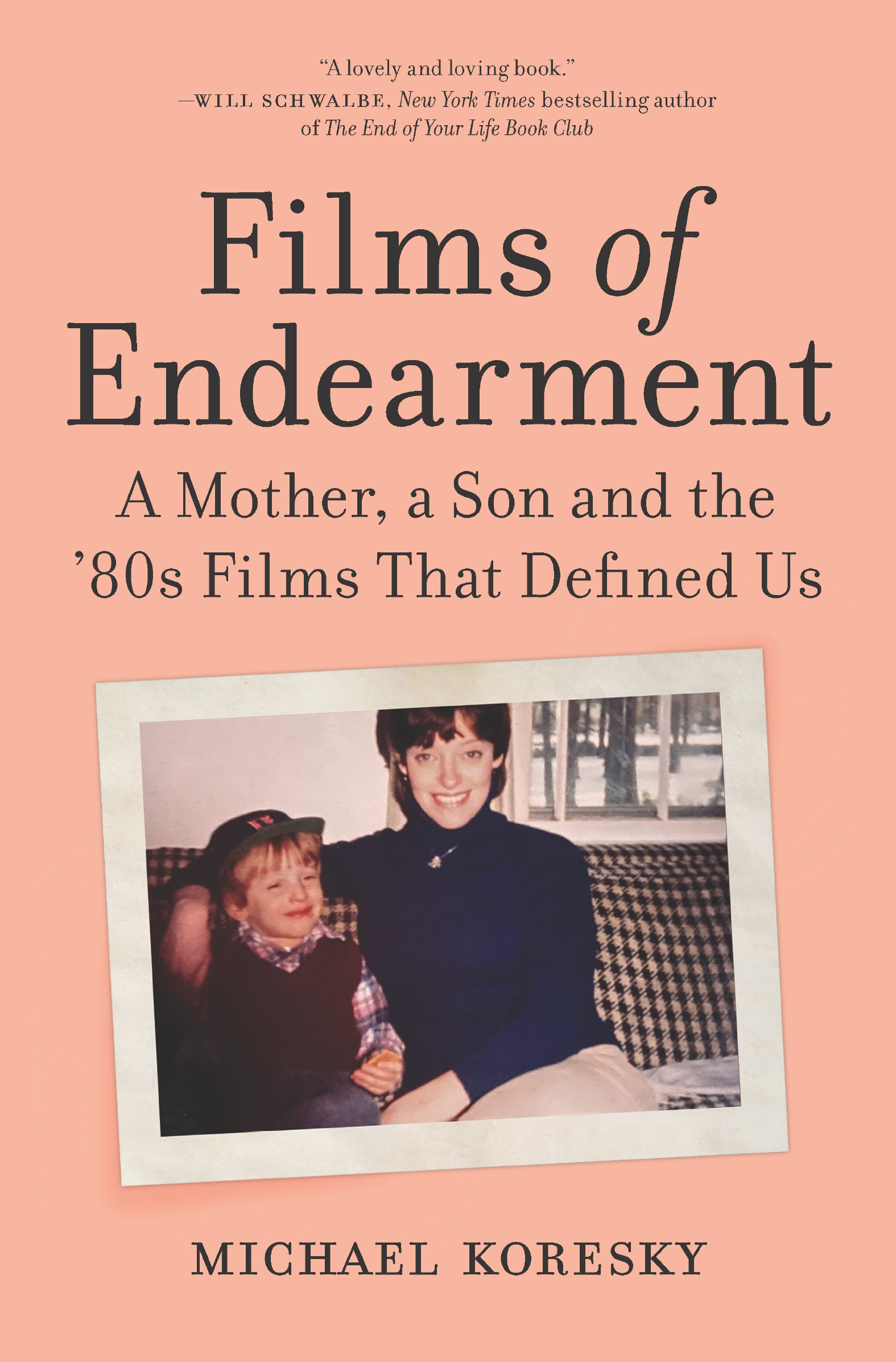

Michael Koresky is a film critic and filmmaker, and editorial director at New Yorks Museum of the Moving Image. He has held staff editorial positions for Film at Lincoln Center and The Criterion Collection, where he continues to work as a freelance programmer. He has been named one of the 100 Most Influential People in Brooklyn Culture by Brooklyn Magazine.

Praise for Films of Endearment

Im not sure I have ever read a book about movies that is as tender and open-hearted as Films of Endearment . Michael Koresky gives us a new way to look at the kind of movies we dont talk about enough even though they live inside so many of us.

Mark Harris, New York Times bestselling author of Mike Nichols: A Life

Spellbinding... Leslie, the New England working woman and mother who instilled a passion for movies in her child, is no less remarkable in her way than the heroines of 9 to 5 , Aliens , or The Fabulous Baker Boys . A testimonial to the way films nourish and connect us.

Molly Haskell, author of Frankly, My Dear: Gone with the Wind Revisited

One of our most generous and engaged critics, Koresky has written a beautiful book that is at once a deeply touching and open-hearted tribute to his relationship with his mother and an ardent love letter to studio filmmaking.

Ari Aster, director of Hereditary and Midsommar

A masterful blend of memoir and movie appreciation.

Meredith May, author of The Honey Bus: A Memoir of Loss, Courage and a Girl Saved by Bees

Nostalgic, incisive, and deeply moving. Koreskys mother gets top billing above Jane Fonda, Sigourney Weaver, and Shirley MacLaine, and deservedly so: A force in her own right, she is the unsung hero from whom he inherited a life-altering love of movies.

Erin Carlson, author of Queen Meryl: The Iconic Roles, Heroic Deeds, and Legendary Life of Meryl Streep

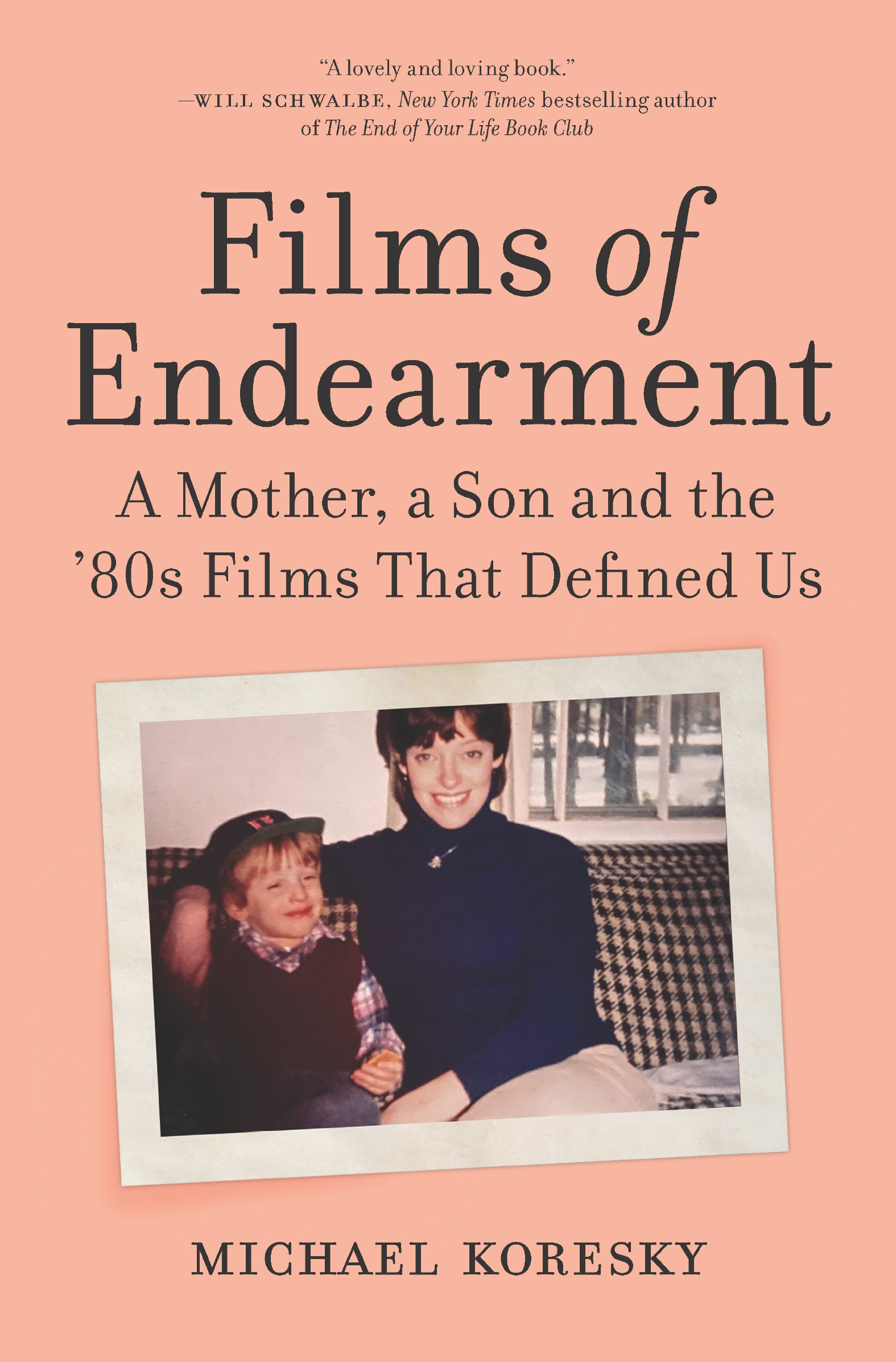

Films of Endearment

A Mother, a Son and the

80s Films That Defined Us

Michael Koresky

For my dad

Contents

Introduction: Home Movies

You must be tired. Its the first thing she says when I get off the bus. Every time. Its usually quickly followed by another statement: You must be hungry.

Parents have a lot of musts to give, a lot to project onto their childrens moods, wants, and needs. My mother is not wrong: Im usually both tired and hungry after the four-and-a-half-hour bus ride from New York to Newton, the Boston suburb where she picks me up. She then drives me to Chelmsford, the much smaller Massachusetts town where I grew up and where she still lives. My dad, who loved driving and adored cars with the fervency of a heartsick romantic, used to be the one to pick me up; this is never out of my mind as she and I ride back home.

We pull off the highway into Chelmsford, and a sense of calm washes over me. The anxiety and intensity of New York are gone for the moment; they belong to someone else, that adult who lives back in that big, ugly-beautiful city, who scoffed at endless subway delays, who rushed across sidewalks before the walk signs timer runs out, who gritted his teeth in agony as the person next to him on public transportation played his music too loud.

Its been an extended period since I was last home, so my mom talks the whole ride, making up for lost time. The latest news about family and friends and neighbors, information about any upcoming singing gigs she has scheduled, what new TV shows shes watching, what shes recently rented from Netflixyes, she still rents the discs. As do I.

As we drive on from the towns center, the neighborhoods grow denser, the houses get smaller, the trees more plentiful. We turn onto winding Walnut Road, with its forty-two houses, all built on suburban tracts in the fifties; our modest house sits in the middle, where the street crooks off at a ninety-degree angleapproaching first-time drivers wrongly assume its a dead end. I still call it our house; its the house I grew up in, the only house Ive ever lived in. Its been painted sky blue for many years, but this surprises me every time. I always think of it as russet brown. The driveway is wide enough to welcome two cars, but theres only one car now.

Weve made it inside. Safe. The house seems to live and breathe, a being unto itself. I notice little biological changes to its lifeblood with each visit: a recently added I HEART My Grand-Dogs magnet on the fridge, or a Life Is Short... Eat Cookies plaque on the wall, or a differently colored teakettle on the stove. This time, theres a plush new carpet running up the staircase that leads to the second floor, the site of my bedroom growing up, where I now dump my travel bags. Though its technically been remade as a guest room, many of my childhood treasures line the shelves that are built into the walls: my 70 Years of the Oscar and The Films of the Eighties coffee table tomes and Pauline Kael and Japanese cinema volumes; my Chris Van Allsburg picture books (my favorite was the rigorously ambiguous The Mysteries of Harris Burdick , each of its stories boiled down to one sentence and an unsettling illustration); my improbable Bram Stokers Dracula souvenir mug. Upon a recent trip I discover in my room a creaky wooden jewelry box full of movie-theater stubs from the nineties. I didnt realize my mother kept them for me; with dates, titles, and cinema names they provide a road map to my entire Massachusetts movie-going experience as a kid.

A light lunch has been prepared, probably a tuna salad or tabbouleh with pita bread. If its fall or winter, we eat in the more formal dining room, as we do now; if spring or summer, hopefully on the screened-in porch, so we can feel the breeze and see the branches of the oak trees sway. It used to not have screens; it started out as a deck, which my dad built with his own two hands when I was almost five. The foundation has remained strong and has supported the family for decades.

Its usually a Saturday when I first get in to Chelmsford, so without too much work to do, I have time, even hours, to talk, to catch up with her. Lunch chatter is full of digressions: how my husband, Chris, is doing and how hard hes working running an arts nonprofit back in New York ( hard ); updates about our dog, Lucy, and my moms cat, Daisy (both sweet, no surprises); if theres anything I need to know about my moms health (broken wrist or a locked-up knee or her heart arrhythmia). We move on to more important topics, like what books were reading or TV shows were watching. Then the most important topic of all: What movie are we going to watch tonight?

Obsession is entirely the wrong word to describe the way Leslie and I talk about movies. Rather, theyre a way of life, a totalizing force that informs our experiences and interactions. When you love movies so desperately, you see the world differently through them and because of them. And you return to them, because movies change as we change, grow as we grow, friends that reveal new facets with every viewing. And like friends, sometimes they can betray you, reveal themselves to be not as caring, not as sensitive, not as sophisticated, as you once thoughtthough this can never completely change the affection, the love, you once felt for them.

My mother instilled this love. My father, Bobby, enjoyed movies, too, as does my older brother, Jonathan, but not to the same level that my mother and I do, not as emotional, moral, and aesthetic inspiration. I was destined to take that love to yet another height. After I spent a childhood watching moviesand watching them, and watching them, and then watching them againthey would become my profession: writing about movies, talking about them, researching them, editing other peoples writing about them, making them. Through my work at such institutions as Museum of the Moving Image, The Criterion Collection, Film at Lincoln Center, and the legendary-to-cinephiles Film Comment magazine, I have been privileged to get close to the world of movie love, to spread its gospel, and to learn more about film than I ever knew there was to learn.

Next page