ALSO BY ROY MORRIS, JR.

The Long Pursuit: Abraham Lincolns Thirty-Year Struggle with Stephen Douglas for the Heart and Soul of America

Fraud of the Century: Rutherford B. Hayes, Samuel Tilden, and the Stolen Election of 1876

The Better Angel: Walt Whitman in the Civil War

Ambrose Bierce: Alone in Bad Company

Sheridan: The Life and Wars of General Phil Sheridan

LIGHTING OUT FOR THE TERRITORY

H OW SAMUEL CLEMENS Headed West

and Became MARK TWAIN

ROY MORRIS, JR.

Simon & Schuster

1230 Avenue of the Americas

New York, NY 10020

www.SimonandSchuster.com

Copyright 2010 by Roy Morris, Jr.

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or

portions thereof in any form whatsoever. For information address

Simon & Schuster Subsidiary Rights Department,

1230 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10020.

First Simon & Schuster hardcover edition March 2010

SIMON & SCHUSTER and colophon are registered trademarks

of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

For information about special discounts for bulk purchases,

please contact Simon & Schuster Special Sales at

1-866-506-1949 or business@simonandschuster.com.

The Simon & Schuster Speakers Bureau can bring authors

to your live event. For more information or to book an event,

contact the Simon & Schuster Speakers Bureau at

1-866-248-3049 or visit our website at www.simonspeakers.com .

Designed by Kyoko Watanabe

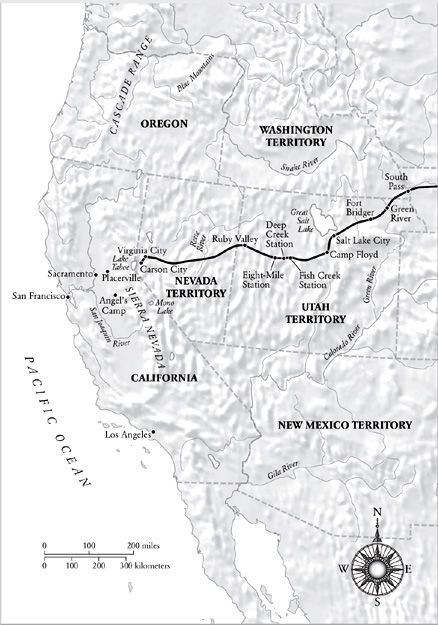

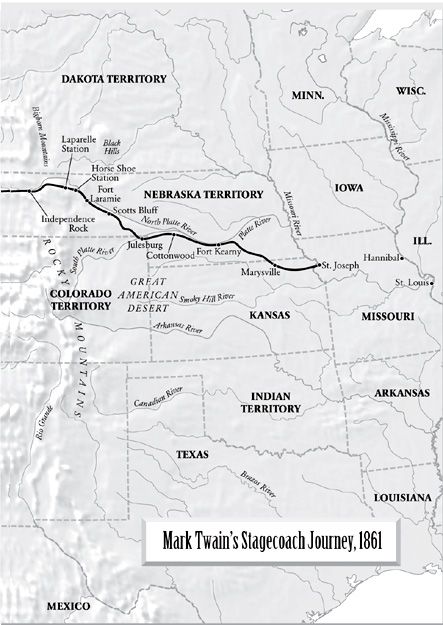

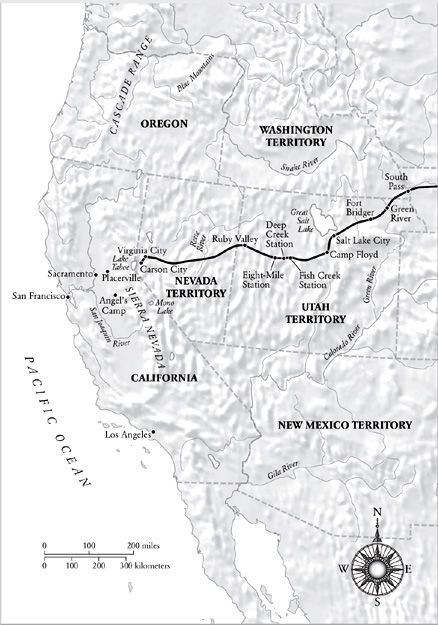

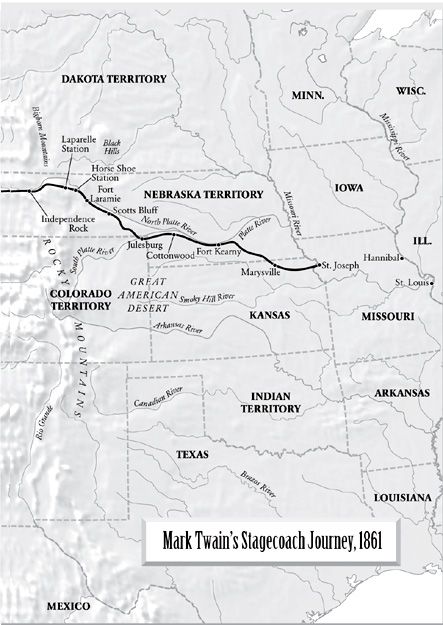

Map by Paul J. Pugliese

Manufactured in the United States of America

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Morris, Roy.

Lighting out for the territory : how Samuel Clemens headed west and

became Mark Twain / Roy Morris, Jr.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

1. Twain, Mark, 18351910TravelWest (U.S.) 2. Authors, AmericanHomes and

hauntsWest (U.S.) 3. West (U.S.)Intellectual life19th century. 4. West (U.S.)

Description and travel. 5. West (U.S.)In literature. I. Title.

PS1342.W48M67 2010

818.403dc22

[B]

2009049221

ISBN 978-1-4165-9866-4

ISBN 978-1-4391-0137-7 (ebook)

ILLUSTRATION CREDITS: Mark Twain Project, The Bancroft Library, University of

California Berkeley: 1, 2, 10, 11, 17; National Archives: 3; Library of Congress: 4, 6,

7, 8, 14, 15, 18; The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley: 5, 9, 12, 13;

The Mariners Museum, Newport News, Virginia: 16

In memory of Susan Woodall Pierce,

19542008.

Nothing so liberalizes a man and expands the kindly instincts that nature put in him as travel and contact with many kinds of people.

MARK TWAIN, 1867

CONTENTS

AUTHORS NOTE

A NYONE VENTURING TO WRITE ABOUT THE SINGULARLY gifted and protean individual who began life on November 30, 1835, in northeastern Missouri as Samuel Langhorne Clemens and became famous the world over as Mark Twain faces an immediate and unavoidable problem: what to call him. His family and his oldest friends called him Sam, or sometimes Sammy; newer friends called him Mark; business associates called him Clemens; his daughters called him Papa; his wife called him Youth. Early in his writing career he tried out various noms de plume, ranging from short and pithyRambler, Grumbler, Josh, Sergeant Fathomto long and clumsyW. Epaminondas Adrastus Perkins, W. Epaminondas Adrastus Blab, Thomas Jefferson Snodgrass, Peter Pencilcases Son, even A Dog-Be-Deviled Citizen. In February 1863, commencing his professional writing career on the Virginia City Territorial Enterprise, he began signing himself Mark Twain. Thats how most people think of him today. The name Mark Twain is as much a trademark, in its way, as Coke or McDonalds or Mickey Mouse. Hes that big.

The generally accepted way to identify Clemens/Twain is chronologically, calling him by whatever name he was using at the time. It makes for occasionally awkward reading, particularly when Mark Twain the writer is describing something he experienced years earlier as Sam Clemens the person, but there is no easier way to do it. Like most previous biographers, I will employ the admittedly arbitrary but convenient method of referring to the subject as Sam or Clemens during his youth and Twain or Mark Twain after he unveiled his famous pen name. As with everything else in this book, its Mr. Mark Twains fault, not mine, and all the blame attaches to him. Credit, where due, is optional.

LIGHTING

OUT FOR THE

TERRITORY

INTRODUCTION

A T THE END OF HIS GREAT ADVENTURE DOWN THE Mississippi River and the joyless labor of trying to make a book out of it, a rather glum Huckleberry Finn pauses to take stock of the situation. Jim is free (and forty dollars richer, compliments of Tom Sawyer), Tom is recovering nicely from his recent gunshot wound, and the odious Pap is long since dead, last seen floating downriver in a ruined house. Everyone, it seems, is happy except Huck. He has his reasons. Toms formidable Aunt Sally, on whose south Arkansas farm Jim finally found his long-delayed deliverance, is threatening to turn her stifling if well-meaning hand toward Huck; she aims, he says, to sivilize him. It is more than a boy can bearthis boy, anyway. He reckons it is time and assume the mantleand burdenof Mr. Mark Twain. Neither he nor American literature would ever be the same.

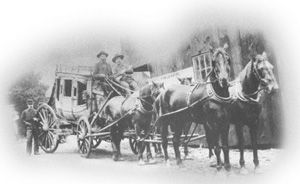

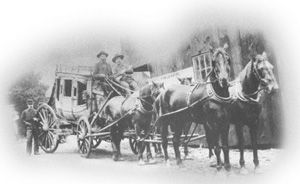

Lighting Out for the Territory: How Samuel Clemens Became Mark Twain is the story of how Samuel Clemens, itinerant printer, Mississippi riverboat pilot, and Confederate guerrilla, became Mark Twain, celebrated journalist, author, and stage performer. As with most of the events in his long and varied life, Twain told it best, recounting his western adventures in one of his most popular books, Roughing It, published in February 1872, a full decade after his trip out west. Like Huckleberry Finn, which appeared in 1885, Roughing It is mostly a true bookwith some stretchers thrown in. It is an appropriately rambling and episodic account of the five and a half years the author spent traveling to and from Nevada, California, and Hawaii between July 1861 and December 1866not coincidentally the same years that bracketed the American Civil War. There is virtually nothing about the war in the bookagain not a coincidence, since leaving the war behind was Twains primary motive for going west in the first place. Except for a brief paragraph about a Fourth of July celebration in Virginia City, Nevada, in 1863 and a slightly longer account of local fund-raising activities on behalf of the United States Sanitary Commission, Twain omits any reference to the greatest and most tragic event of his lifetime. Indeed, Roughing It could have taken place at any time after 1849, when the first gold rushers headed for California along pretty much the same route that Sam Clemens and his brother Orion (pronounced OR-ee-un) followed a dozen years later. It is a timeless book in more ways than one.

Next page