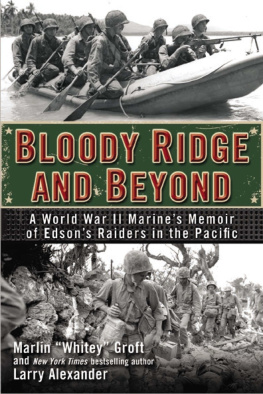

Bloody Beaches

History of the Marine Raiders in the Pacific War

Daniel Wrinn

Contents

Get your FREE copy of WW2: Spies, Snipers and the World at War

Never miss a new release by signing up for my free readers group. Learn of special offers and interesting details I find in my research. Youll also get WW2: Spies, Snipers and Tales of the World at War delivered to your inbox. (You can unsubscribe at any time.) Go to danielwrinn.com to sign up.

Creating the Raiders

In February 1942, the Commandant of the Marine Corps, General Holcomb, ordered the formation of a new unit that would be known as the 1st Marine Raider Battalion.

This elite fighting force and its three sister battalions went on to gain immense fame for their fighting prowess in World War II. But there was more to the story than simple tales of combat heroics. The growth, inception, and sudden end of the raiders revealed a great deal about the conduct and development of amphibious operations during the war.

The Marine Corps faced a considerable challenge of expanding its forces from 19,000 to 450,000 men at the beginning of World War II. The Marine Raiders attracted more than their share of strong leaders. This resulted in the combination of courage, organization, and personalities that made one of the most exciting chapters in the history of the Marine Corps.

There were two independent forces responsible for the creation of the raiders in early 1942. Historians have traced one of these to the friendship developed between FDR and Evans Carlson. Because of his experiences in China, Evans Carlson was convinced that guerrilla warfare was the wave of the future.

Captain James Roosevelt, the presidents son, also believed in the strategic value of guerrilla warfare. Presidential confidant William Donovan also pushed a similar theme. Donovan had been an Army hero in World War I and now worked as a senior advisor on intelligence matters. He wanted to create a guerrilla fighting force to infiltrate occupied enemy territory and assist resistance fighters. Donovan made a proposal to FDR in December 1941. In January, the younger Roosevelt wrote to the Commandant of the Marine Corps. He recommended creating a unit for purposes similar to the British commandos and the Chinese guerrillas.

In early 1942, the war was going badly for the Allies. The Germans had forced the British off the continent of Europe. The Japanese had swept the United States and Britain from the majority of the Pacific. The Allies were too weak to slug it out in conventional battles with the Axis powers. Guerrilla warfare and quick raids seemed to be viable alternatives. British commandos had already conducted numerous forays against the European coastline, and Winston Churchill wholeheartedly supported this concept to FDR.

While Marine Commandant General Holcomb believed that any properly trained Marine unit could perform amphibious raidshe ultimately yielded to the high-level pressure and organized the raider battalions.

Two other men were responsible for the formation of the raiders. General Holland M. Smith had created the first manual on amphibious operations in 1935. During the early days of World War II, General Smith faced the difficult task of trying to convert that paper doctrine into a fighting reality. As a Brigadier General, Smith took command of the 1st Marine Brigade in fleet landing exercises in early 1940 in the Caribbean.

He realized that a lack of adequate landing craft made it impossible to quickly build up combat power on a hostile shore. The initial assault elements would be vulnerable to counterattack and defeat, while most amphibious forces remained on board their transports.

To solve this problem, General Smith decided to employ the newly developed high-speed destroyer transports or APD (AP for transport and D for destroyer). He outlined a plan to land a company of the 5th Marines via rubber boats at H-3 hours before dawn at a point away from the primary assault beach. This force would then advance inland and seize key terrain on the beachhead. This would protect his main landing force from a counterattack.

One year later, General Smith had three APD high-speed destroyer transports. He designated three companies of the 7th Marines embarked on the ships as his Mobile Landing Group. During this exercise, these units made night landings protecting the main assault or executed diversionary attacks.

General Smith proposed future assaults with three distinct waves. The first wave would be composed of fast-moving forces seizing critical terrain before the main assault. The first element would be a parachute regiment, an air infantry regiment, and a light tank battalion with at least one high-speed destroyer transport. Once the beachhead was secured, the more bulky combat units of the assault force would follow ashore. The third wave would consist of the reserve force and service units.

In the summer of 1941, General Smith was able to put these ideas into action. He now commanded the AFAF (Amphibious Force Atlantic Fleet), consisting of the 1st Marine Division and the Armys 1st Infantry Division. During maneuvers at the Marine base in New River, North Carolina, General Smith embarked the 1/5 Marines in six APDs, making them an independent command reporting directly to his headquarters.

This operational plan attached the Marine divisions only company of tanks and its single company of parachutists to the APD battalion. With all his aviation assets working in direct support, the mobile force could swiftly move inland to surprise and destroy enemy reserves while also taking control of critical communication lines. General Smith called this: a spearhead thrust from around a hostile flank.

Smith did not randomly select the 1/5 Marines for this role. In June 1941, he chose Colonel Merritt Red Mike Edson to command this battalion. Smith referred to Edsons outfit as the light battalion or the APD battalion.

When the 5th Marines and other elements of the 1st Marine Division moved to New River that fall, the 1st Battalion stayed behind in Quantico with Force headquarters. The battalion was placed in a category separate from the rest of the division, which it was still technically a part of. Colonel Gerald Thomas, the division operations officer, referred to the battalion as the headquarters plaything.

Edsons unit was unique in many ways. In an August 1941 report, Edson evaluated the organization and missions of his unit. He believed his battalion would focus mainly on raids, reconnaissance, and other special operations. He envisioned his battalion as a waterborne version of the parachutists. His battalion would depend on mobility and speednot firepower.

Since APDs could neither embark nor offload vehicles, the battalion had to become entirely foot mobile once ashorejust like the parachutists. Edson recommended a new organizational table that made his force lighter than other infantry battalions to achieve this rapid mobility. He wanted to trade his 81mm mortars and heavy machine guns for more lightweight models. With fewer of these weapons, theyd have larger crews to carry ammunition. Given the limitations of the high-speed transports, each company would be smaller than their standard counterparts. There would now be four rifle companies, a headquarters company, a weapons company, and a large demolitions platoon. Their main assault craft would be 10-man rubber boats.