CHAPTER 1

Photographing George Washington

In February 1839 the Boston Daily Advertiserpublished news from France of a curious invention lately made by M. Daguerre; for making drawings. The writer noted that while the manner in which the camera obscura produces images of objects, by means of a lens, is well known, Louis-Jacques-Mand Daguerres contribution was a method of fixing the image permanently that did so by the agency of the light alone. The article went on to explain that Daguerres machine could make accurate drawings of any object indeed, or any natural appearance may be copied by it. One man who had observed Daguerres efforts compared the new technology to a kind of physical retina as sensible as the retina of the eye.

As the Daily Advertisers choice to publicize Daguerres efforts illustrates, Americans were keenly interested in the idea of photography. Some enthusiasts in the late 1830s were experimenting with photogenic drawing, the process of exposing objects to light-sensitive paper pioneered by William Henry Fox Talbot in England.

After the French government formally presented the daguerreotype to the public in August 1839, copies of European newspapers describing how to perform the new process made their way across the Atlantic to the United States. The daguerreotype quickly took off in the United States, eclipsing other nascent modes of photography.

A daguerreotype is a one-of-a-kind, fixed photographic image made by the action of light upon a plate sensitized by chemical solutions. According to photo process historian Mark Osterman, a copper plate is coated with light-sensitive silver, the plate is exposed in the camera, and then the hidden image is revealed by allowing the fumes of heated mercury to play upon the silver. The daguerreotype is then washed in a fixing solution to make the image permanent and, finally, toned with a solution containing gold chloride.

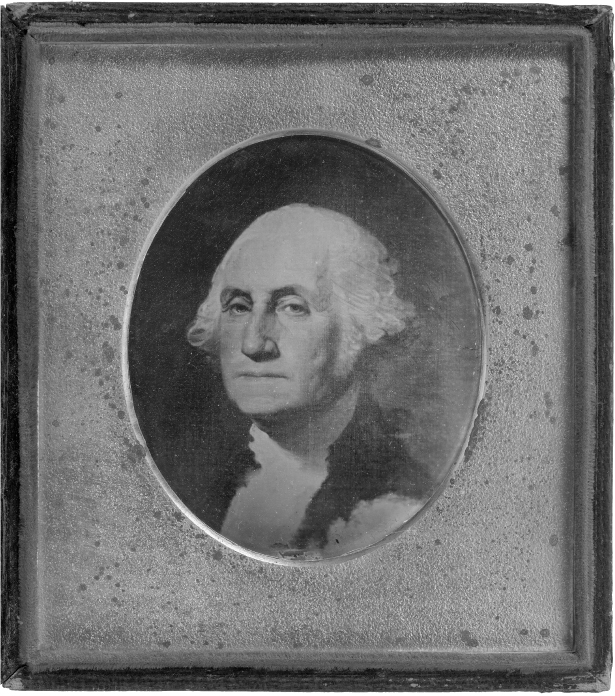

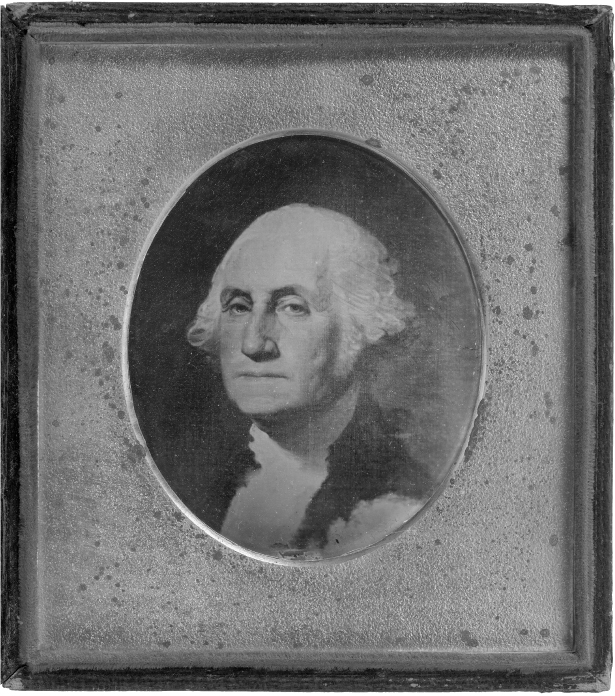

Almost as soon as Americans started making daguerreotypes, they made daguerreotypes of George Washington. The fact that he was unavailable to be photographed from life was no obstacle. Though he died in 1799a full forty years before photographys inventionthe nations first president nevertheless appeared as a subject in daguerreotypes of busts, painted portraits, and prints, ironically making daguerreotypes of Washingtons image some of the earliest presidential photographs. Take, for example, a daguerreotype of Gilbert Stuarts famous, yet unfinished, 1796 Athenaeum portrait of George Washington. Roughly three inches tall by two and a half inches wide and easily held in one hand, the lightly tarnished, quarter-plate daguerreotype of Washington is preserved behind glass and a gilded mat, cushioned by red velvet, and protected by a worn wooden and leather hinged case. But its mirrored surface still clearly offers up Washingtons painted gaze, one that is familiar to us today in large part because we carry it in our wallets on the U.S. dollar bill.

Figure 1.1:John Adams Whipple, daguerreotype of portrait of George Washington by Gilbert Stuart, 1847. (National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution; gift of Helen Hill Miller.)

When the case is opened, a message appears opposite the Washington image. In embossed letters on a red velvet background, a tiny brass plate reads:

DAGUERREOTYPED BY

JOHN A. WHIPPLE

NOV. 15TH 1847.

The daguerreotype and its tiny brass plate invite several questions. What, precisely, has been daguerreotyped here? At first glance, the answer would seem simple: Whipple has made a daguerreotype of a famous painting of George Washington. But why? To share Stuarts famous portrait with others There are no definitive answers to these questions. Nevertheless, the practice of photographing George Washington offers a helpful point of entry into this books exploration of how presidents have helped to shape photography across its history. Because it turns out that once Americans got photography, they needed a photographic George Washington.

Whipples Washington

John Adams Whipple worked as a photographer in Boston starting in the 1840s, and by the 1850s he was a well-known and well-regarded practitioner. Whipple grew up with an interest in chemistry and came to photography while working as a supplier of photographic chemicals in Boston. For an art of sun-painting that relied on the exposure of its subject to a light-sensitive medium, a clear sky was essential.

Today Whipple is remembered for his contributions to the science of photography and the photography of science. For example, in 1850 Whipple and Black patented a process for making paper prints from glass negativeswhat they called crystalotypeswhich opened the door to the printing of photographs on paper in later decades.

Closer to the subject of his Washington daguerreotype, Whipple also showed interest in the photography of art and in images related to the nations founders. The frontispiece constituted perhaps one of the earliest examples of a photograph being printed in or with a book.