Copyright 2021 L. Jon Wertheim

All rights reserved

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to or to Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 3 Park Avenue, 19th Floor, New York, New York 10016.

hmhbooks.com

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Wertheim, L. Jon, author.

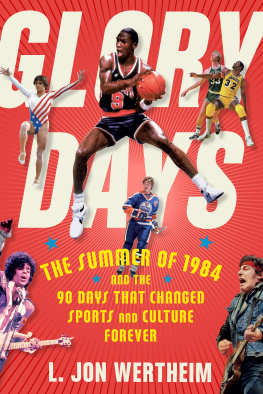

Title: Glory days : the summer of 1984 and the 90 days that changed sports and culture forever / L. Jon Wertheim.

Description: Boston : Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2021. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2020033845 (print) | LCCN 2020033846 (ebook) | ISBN 9781328637246 (hardcover) | ISBN 9780358449058 | ISBN 9780358449393 | ISBN 9781328637901 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: SportsHistory20th Century. | Nineteen eighty-four, A.D.

Classification: LCC GV576 .W45 2021 (print) | LCC GV576 (ebook) | DDC 796.09048dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020033845

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020033846

Cover design by Brian Moore

Cover photographs: Bob Thomas Sports Photography / Getty Images(Retton); Andrew D. Bernstein / NBAE / Getty Images (Johnson / Bird); Heinz Kluetmeier / Sports Illustrated / Getty Images (Jordan); BruceBennett Studios / Getty Images (Gretzky); Richard E. Aaron / Redferns /Getty Images (Prince); Richard McCaffrey / Michael Ochs Archive / GettyImages (Springsteen)

Author photograph John Filo

v1.0521

Part of the introduction was first published, in different form, as the 2014 article Rare Air Time: Michael Jordan, the 84 U.S. Olympic Trials and Me, by Jon Wertheim for Sports Illustrated online.

To my family family

To the Sports Illustrated family

Glory Days, well, theyll pass you by.

BRUCE SPRINGSTEEN,

from Born in the U.S.A., released June 4, 1984

REPORTER: Is it true you can fly?

MICHAEL JORDAN: No. Well, maybe for a little.

Introduction

Though dripping with modest Midwest charm, my hometown, Bloomington, Indiana, wasand still isa somewhat sleepy college town. Especially so between semesters at Indiana University. When the students arent around, the population plunges by half.

But in the late spring of 1984, when I was 13 years old, the usual quiet was ruptured. Bloomington was enlivened and invigorated that April because the circus had come to town. The attractions, though, werent tightrope walkers and jugglers and trapeze acts; the menagerie instead featured a collection of extraordinarily tall and extraordinarily athletic young men, ages 18 through 22.

Bob KnightIndiana Universitys famously unyielding coach and the most powerful figure at the time not just in the Hoosier State but in all of college basketballwas tasked with putting together the roster of the U.S. mens basketball team that he was going to guide that summer at the Los Angeles Olympics. These were still the days when the Games demanded amateurism, before NBA players were eligible to compete. And these were still the days when coaches were absolutists, wielding their authority like unchecked dictators.

The players werent asked to be on the team; they auditioned for a spot. And there was no national training center. The hopeful applicants came to Knights domain and worked on Knights timetable. They went through a series of tryouts for Knight and his staff. Like Roman emperors assessing gladiators, the assessing coaches either gave performers a thumbs-up or sent them home.

In keeping with Knights entire mode of being, the players were not exactly coddled. Joe Kleine, a Missouri kid who played at the University of Arkansas, recalls flying into the Indianapolis airport. We all picked up our own bags and then piled into these buses. It was like going to Camp Wong-a-Monga or whatever. Except youd look around the bus and it was Michael Jordan across the aisle and Charles Barkley in the row behind you and Patrick Ewing in the row ahead of you.

When the players arrived in Bloomington, they were assigned spartan rooms at the Indiana University student union. They mostly ate cafeteria food. They were transported around town in maroon vans, three players per row. The tryouts were held at the IU Fieldhouse, a no-frills gym, redolent mostly of Ben-Gay wintergreen and an indifference to showering.

When practice was over, the players were on their own, ambling around town, sometimes accepting rides to the movies from strangers. Soon everyone in town had a tale. They watched an already rotund Charles Barkley devour an entire pizza, somehow smiling and laughing and talking the whole time. They drove Patrick Ewing home from a screening of The Karate Kid at the College Mall Cinema when his scheduled van ride didnt show up. They played pool against Chris Mullin or Pac-Man against Wayman Tisdale.

Up and down the roster, the players were exceptionally cool. They were uncorrupted by fame and wealth, but, then again, they had little of either back then. What they had instead: a giddiness about the Olympics and, more generally, their luminous futures. Many would be drafted by NBA teams that summer. But they came across as college kids, with college tastes.

Even so, one player projected a different level of magnetism and charisma.

Wearing Bermuda shorts, collared shirts, leather Top-Siders, and a generous smile, Michael Jordan walked around with an easy confidence. Like everyone else, Jordan didnt know what successes awaited himthat he would eventually drive every other athlete on the planet into the shadows. But his disposition alone suggested that, at least at some level, he sensed that his future brimmed with possibility.

Jordan always looked up and out, happyor at least not annoyedto be recognized. He joked easily, in a deep voice, and often offered a rich laugh that originated in the depths of his belly. Though he was a proud son of North Carolina, his voice was flecked with only the slightest southern accent. He was quick to dispense nicknames. And not just to his teammates. One day he spotted me, age 13, carrying a tennis racket. Hey, John McEnroe! he said, miming tennis strokes. When are we gonna play?

Most of Bloomington looked at Michael Jordan somewhat indifferently in the summer of 1984, as he ordered a smoothie at the Chocolate Moose ice cream joint, or lost 18 holes of Putt-Putt, only to shoot the winner a scalding stare and demand an immediate rematch. This time for real, no more playing around.

Of course, Jordan possessed sports ultimate trump card: talent.

Hed just finished his third season at the University of North Carolinaironically, losing to a Knight-coached Indiana team in his final college gameand most experts pegged him as a high lottery pick, provided, that is, that he would skip his senior season and go to the NBA.

During the Olympic Trials, Jordans aura grew as he distanced himself from the others. Shod in powder-blue Converse high-tops, leftovers from his North Carolina basketball wardrobe, Jordan executed moves other players wouldnt think to attempt, much less pull off.

Knight, not one prone to insincere praise, much less to gushing, could not conceal the admiration he had for his shooting guard. Knight warned that any NBA team foolish enough to pass up drafting Jordan would regret the decision. Jordans game is made for the NBA, he declared. When he raved about Jordan, it was as much about his competitive resolve and comportment as it was his quickness or the moves that defied the laws of physics and geometry.

Here was Knight on Jordan that summer, long before MJ played his first NBA game: The kid is just an absolutely great kid. If I were going to pick the three or four best athletes Ive ever seen play basketball, hed be one of em. I think hes the best athlete Ive ever seen play basketball.