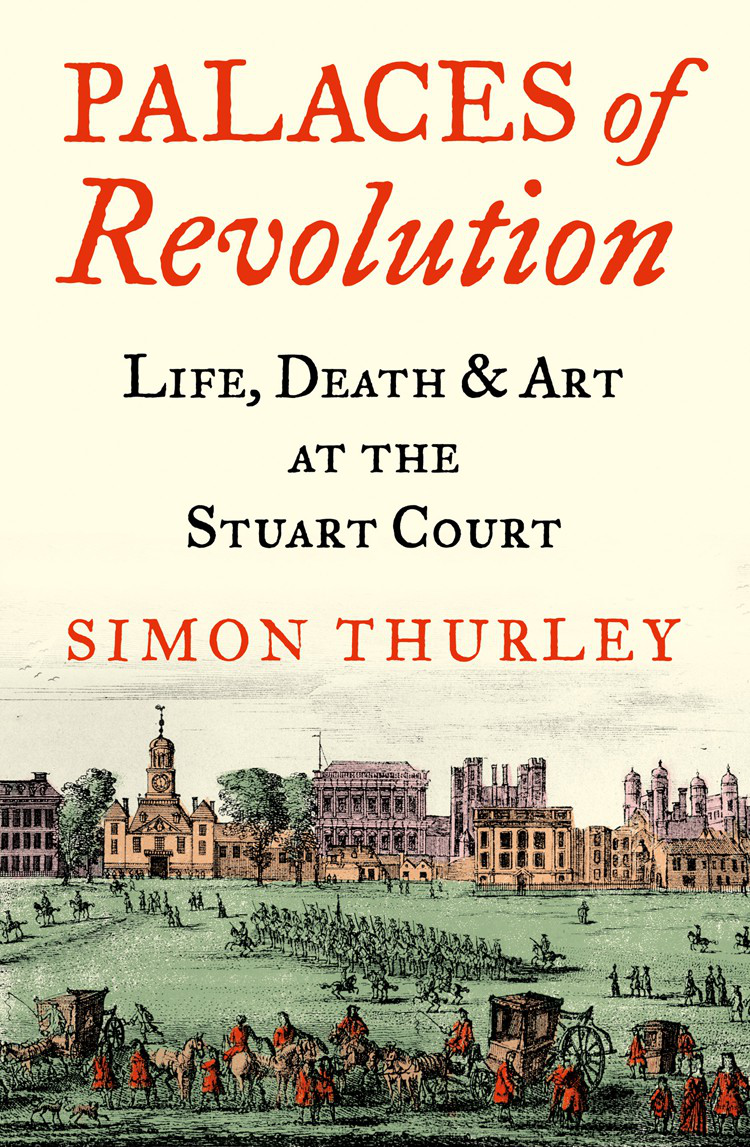

PALACES OF REVOLUTION

Life, Death and Art at the Stuart Court

Simon Thurley

William Collins

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

WilliamCollinsBooks.com

This eBook first published in Great Britain by William Collins in 2021

Copyright Simon Thurley 2021

Images individual copyright holders

Cover image Print Collector/Getty

Simon Thurley asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008389963

Ebook Edition August 2020 ISBN: 9780008389970

Version: 2021-08-13

For Maud

Contents

W hen I laid down my pen after completing a history of Henry VIIIs palaces in 1992 I decided that my next book would be about the houses of the Stuart kings. It was a slightly more ambitious task than I first imagined. Ten books and some thirty-five articles later I have finally completed it. The intervening twenty-eight years were spent writing the history of individual houses that formed the principal components of Stuart royal life. Books on Hampton Court, Whitehall, Somerset House, Windsor Castle, Oatlands, St Jamess and articles on Greenwich, Royston, Newmarket and Winchester were necessary steps in understanding the architecture of the Stuart court and its place in national, and international history.

Working first at Historic Royal Palaces, then the Museum of London and latterly at English Heritage for near three decades gave me privileged access to buildings, excavations, research, archives and the work of other scholars. Meanwhile colleagues in the Royal Collection, the British Museum, the V&A, the RIBA drawings collection and elsewhere have been generous enough to share and discuss their own research with me.

This book, in many senses, is a sequel to my work on Tudor royal architecture and court life, but it is also a stand-alone study of the Stuart world, a world far more cosmopolitan than that of the Tudors a fact reflected in the geographical reach of what follows. The century or so I cover (16031714) was one of extraordinary political, economic and cultural change and the buildings that I describe were the stage upon which most of the important events of the period were enacted. Some of those buildings remain and can be visited today; many are gone, and my task has been to visualise these lost places both from documents and surviving plans and views. Archaeology has played its part, and some of the most important sites have been reconstructed from buried fragments of brick and stone. An important feature of this book is the many plans and maps that try and convey a lost world of remarkable places.

The decades since 1992 have also seen an explosion of interest in the Stuart monarchs, their courts, consorts, houses and cultural interests. Many of the scholars working in this sphere have become friends and I have hugely benefited from their research. An important source of debate has been the Society for Court Studies seminar series, a crucial forum for new thinking about courts.

Over the years many people have helped and advised me, most of whom are acknowledged in my previous publications; but some have been particularly generous with their help with this book and I would like to thank Warwick Rodwell, John Sutton, Andrew Barclay, Anna Keay, Anthony Geraghty, Judith Curthoys, Stephen Conlin, Olivia Fryman, Tom Campbell, Paul Pattison, Edward Impey, John Goodall and Mike Turner. Andrew Barclay and Anna Keay generously read the whole manuscript, diligently pointing out errors and making excellent suggestions. The editorial team at William Collins, Hazel Eriksson and Sally Partington, have also made many improvements for which I am grateful.

I would also like to thank my audiences at Gresham College who were the recipients of several chapters of this book in lecture form and asked penetrating questions and made useful comments. My lectures can be watched at https://www.gresham.ac.uk/series/theatres-of-revolution . Also accompanying this book is my website www.royalpalaces.com which contains much additional material.

Finally, I would like to thank my agent Andrew Gordon and my Commissioning Editor Myles Archibald for believing in this book, my assistant Kate Francis without whom nothing happens, least of all writing books, and my wife Anna Keay. Anna has worked on the Stuarts for as long as I have. Much of this book was written during the Covid 19 lockdown of 2020 and, as I worked on my text, Anna sat on the other side of our library in Norfolk writing her book Interregnum (also published by William Collins). Long evenings comparing notes and debating Stuart history with her has made this book immeasurably better. For that, and for everything else, I thank her.

Kings Lynn

May 2021

Authors note

In quotations from contemporary sources, I have modernised spelling and punctuation to make it easier to read. The endnotes direct the reader to the original source.

Dates are shown as Old Style, but the year is calculated from 1 January. On occasion, where clarity requires it, dates are written 1687/8.

This book was completed during the global pandemic of 202021 and as a result it proved impossible to undertake some of the normal checking of primary sources in the National Archives and elsewhere. As a result, it is possible that mistakes remain in transcriptions and citations.

The sources upon which my plans are based are listed in the endnotes.

Royal meltdown

G old melts at 1,064 degrees centigrade. The know-how to reach this temperature had existed since ancient times, and the great brick furnaces in the Tower of London Mint were fired by oak charcoal, like that used by goldsmiths for a millennium or more. Clay crucibles, about nine inches high and six inches in diameter were packed into the burning charcoal whose heat was intensified by air directed from vast bellows aimed at their base. When the gold inside had liquefied, iron tongs extracted the brimming vessel and allowed the molten metal to be poured into an oiled mould.

The melting house in the Tower was in the outer ward, squeezed between two high medieval curtain walls. It was not in use every day, but the melters fired up their furnaces when there was enough material to fill their crucibles. They did not use gold ore, which was unavailable in England, but recycled plate, coin and jewellery brought into the Mints plush Office of Receipt. The melters were actually subcontracted to the Master of the Mint and were managed, from the mid-1620s, by a goldsmith, Sir John Wollaston. His was a great contract to have as he charged sixpence a pound for melting gold and two pence for silver. He died an exceedingly rich man.