Few New Zealand politicians have had a greater impact on their country than Michael Cullen. From a ringside seat in the brutal Rogernomics era to being the steward of some of our best financial results and the architect of some of our most enduring social security programmes, he has been there for almost forty years of significant change.

HON GRANT ROBERTSON, DEPUTY PRIME MINISTER

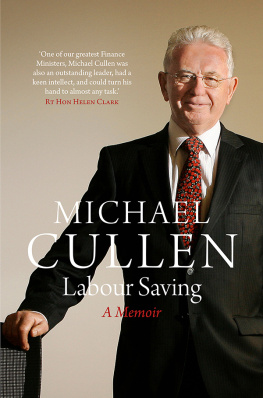

One of our greatest Finance Ministers, Michael Cullen was also an outstanding leader, had a keen intellect, and could turn his hand to almost any task. While the New Zealand Superannuation Fund, KiwiSaver, Working for Families, major Treaty settlements, and many other initiatives will be among his lasting legacies, this book highlights his role as a thinker, doer and builder in a long-standing Labour and social democratic tradition.

RT HON HELEN CLARK

Sir Michael Cullens combination of intellect, intelligence, political acumen and mordant wit were second to none of the MPs and ministers I knew in my half-century watching politics from the parliamentary press gallery, whose members he disdained. Self-styled in this account as an open-economy social democrat and fiscally dry Keynesian, Sir Michael was a rising young MP and then a socially reforming minister in the revolutionary 198490 Labour government, a central figure in Labours rebuild and reframing in the 1990s, and a powerful Finance Minister in the 19992008 Labour-led government, joined at the hip with Prime Minister Helen Clark. Sir Michaels capacious memoir at times revealing of his personal fragilities adds a valuable particular perspective to our understanding of a turbulent three decades.

COLIN JAMES, POLITICAL JOURNALIST AND COMMENTATOR

Authors note: All monetary amounts in this book are expressed in New Zealand dollars unless otherwise specified.

First published in 2021

Copyright Michael Cullen, 2021

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher.

The extract from Burnt Norton by T S Eliot quoted on page is reproduced with kind permission of Faber and Faber Ltd.

The images featured in the picture section are from the authors private collection; the cartoons by Tom Scott and caricatures by Murray Webb are reproduced with kind permission of the artists.

Allen & Unwin

Level 2, 10 College Hill, Freemans Bay

Auckland 1011, New Zealand

Phone: (64 9) 377 3800

Email:

Web: www.allenandunwin.co.nz

83 Alexander Street

Crows Nest NSW 2065, Australia

Phone: (61 2) 8425 0100

A catalogue record for this book is available from the National Library of New Zealand.

ISBN 978 1 98854 785 5

eISBN 978 1 76106 205 6

Design by Kate Barraclough

Cover photograph by Stuff Limited

When Adam delved [dug] and Eve span [spun], who was then the gentleman?

JOHN BALL DURING THE PEASANTS REVOLT (1381)

I think that the poorest he [person] that is in England hath a life to live, as the greatest he [person].

COLONEL RAINSBOROUGH LEADING THE LEVELLERS IN THE PUTNEY ARMY DEBATES (1647)

Words move, music moves

Only in time; but that which is only living

Can only die. Words, after speech, reach

Into the silence.

T S ELIOT, BURNT NORTON (1935)

This book started out as brief notes on my personal life to be added to my voluminous parliamentary papers, which are in the Hocken Collections in Dunedin. These notes very quickly began to grow into a substantial book. It became primarily a book about politics, in particular the policy part of that word. Special attention has been paid to a small number of issues which remain controversial or where the received wisdom seems to me to be wrong. Some will think I have probably at times been a little harsh about my opponents, both inside and outside the Labour Party. My opinions in this book are genuinely held, and are based on my own recollections, the facts as I know them to be, my experiences and a range of published and unpublished sources. I have tried hard not to project backwards but, as a historian by training and original profession, I know how difficult that is.

I began writing this book soon after giving up the majority of my jobs in early March 2020 for health reasons. It turned into a form of therapy for my feelings of loss at no longer contributing to public life in the way I had been used to, in various ways, for forty years. Circumstances, including the restrictions imposed as a result of the Covid-19 outbreaks, meant I could make only one brief visit of a little over two days to consult my papers in the Hocken Collections. I have largely, therefore, relied on online sources such as Hansard and ministerial statements and speeches to jog my memory. Stephen Mills of UMR was kind enough to send me its monthly polling results, dating back to the 1980s. Former colleagues, notably Helen Clark and Stan Rodger, sent me helpful material. My friends Lindy Winterbourne and Dave Keet arranged with their son, Jackson, for me to have free access to The Knowledge Basket, an online source which is very usefully complementary to Historical Hansard (the government online source). I have been conscious throughout of not knowing how much time I would have to write this book, which is the only excuse I have for what I am sure are a number of factual errors. I want to thank Kay Boreham, and my former colleagues Trevor Mallard and Pete Hodgson, for reading earlier drafts and making many helpful suggestions. All interpretations are my own, unless otherwise indicated.

A special thank you to Jenny Hellen, Matt Turner and all those at Allen & Unwin who took on the task of editing, publishing and promoting this book. Finally, to two special women in my life. First, Helen Clark, without whom, rather obviously, this book would never have been written, who supported me all through our political partnership, and who was instrumental in persuading Allen & Unwin to take the book on. Last, and most of all, my wife and former parliamentary colleague, Anne Collins, my very special companion, lover and supporter for over thirty years.

Michael Cullen

Port hope

February 2021

I was born at home in Enfield, London, on 5 February 1945, in the last stages of the Second World War. My mother, Ivy May Cullen, was suspected of having tuberculosis, which was why I was not born in hospital. My father, John Joseph Thomas Cullen, was at the time an aircraftman in the RAF, repairing aircraft instruments. In civilian life he was a spectacle-frame maker, a skilled trade. There was, therefore, a degree of insecurity about my birth. But this was as nothing compared with my mothers. She was born on 15 August 1914, days after the start of the First World War. Her father, James Henry Taylor (b. 1884), was a reservist in the Yorkshire Light Infantry and had been called up immediately, sent to the front, and captured within days. My grandmother, Rose Taylor (ne Chisholm, b. 1881), did not know for about six months whether he was alive or dead. With three daughters, one just born, and no personal or family wealth, the future must have looked bleak.

Both my maternal grandparents grew up in serious poverty. I did my MA thesis in 1967 at Canterbury University on Poverty in London, 18851895. Using the remarkable social surveys of the time led by Charles Booth, I was able to pinpoint the areas they grew up in. My grandmothers street was classified Very poor bordering on the semi-criminal. My paternal grandmother, Alice Cullen (ne Faithfull, b. 1882), was one of three children; by the time of the 1881 census, her father, John, had died, leaving her mother, Elizabeth, dependent on earnings as a charwoman plus the rent from a male lodger. My paternal grandfather, Edwin (Ted) Thomas Cullen, was the exception to this story of ancestral poverty. He was, at the time of my fathers birth in 1909, described as a tram conductor. By the time of my parents wedding in 1936 he was described as a hot-water fitter. His father was a lithographer, and probably well paid by the working-class standards of the time, but Teds parents offset that by having at least ten children. This may help explain why Teds son, my father, was an only child. Ted died in 1939, well before I was born. Further back still, the Cullen males in the late seventeenth, eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries were agricultural labourers in Somerset, in the area to the south of the city of Wells. Teds grandfather moved to London some time in the 1840s.

Next page