Contents

Guide

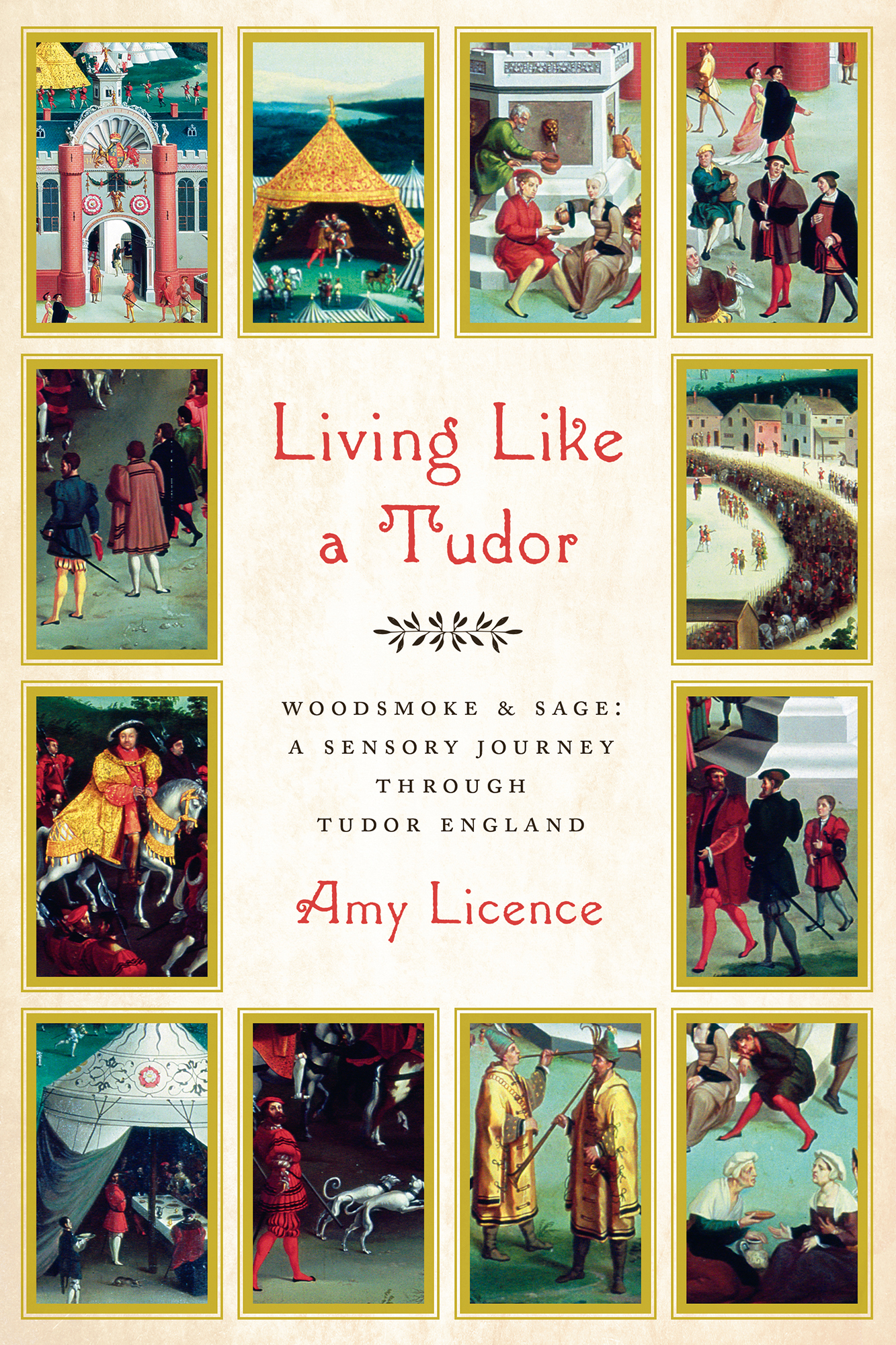

Living Like a Tudor

Woodsmoke & Sage : A Sensory Journey Through Tudor England

Amy Licence

LIVING LIKE A TUDOR

Pegasus Books, Ltd.

148 West 37th Street, 13th Floor

New York, NY 10018

Copyright 2021 by Amy Licence

First Pegasus Books cloth edition November 2021

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in whole or in part without written permission from the publisher, except by reviewers who may quote brief excerpts in connection with a review in a newspaper, magazine, or electronic publication; nor may any part of this book be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or other, without written permission from the publisher.

ISBN: 978-1-64313-815-2

Ebook ISBN: 978-1-64313-816-9

Cover design by Faceout Studio, Molly Von Borstel

Cover image from Bridgeman images and Shutterstock

Distributed by Simon & Schuster

www.pegasusbooks.com

INTRODUCTION

Woodsmoke and sage, peacocks and cinnamon, falcons and linen.

These were the textures of the Tudor world, woven through gowns, served up at feasts, lingering in the air. Life is always a tactile experience and no matter what higher ideologies of politics, religion or science were occupying the minds of our ancestors, daily life was sustained by the physical fabric of environment, both immediate and distant. The Tudors reached towards abstract concepts standing on the solid foundations of empiricism, and the world they created both reflected and informed their understanding of self.

As a 12-year-old girl devouring an illustrated history of the past, I had something of an epiphany. Here was a book that gave serious attention to cooking in the Tudor kitchen, the games children played, what herbs were used to make perfume, what underwear they wore: all the things I assumed were unworthy of being a proper subject of study. It was a revelation. History was suddenly a tactile experience, relatable to mine. I could see my own morning breakfast, dressing, my walk to school, friends in the playground, queuing at the KitKat machine in a new light. These were points on a graph that might have shifted slightly, but they were consistent with the journey of human experience, just as a 12-year-old girl in 1485, or 1585, would have woken, eaten, dressed, interacted, sought a treat.

Only in recent years has the history of material culture been taken seriously. What people ate, or wore, or how they decorated their houses, was too often dismissed as a frippery, mere window dressing or, even worse, vulgar, while the proper academic study continued elsewhere. Domestic, daily and trivial aspects of life were frequently the sphere of marginalised figures such as women, children, servants and minorities. It was almost inconceivable that kings might eat and use the toilet, too. Then, a number of factors created a shift in the popular imagination: interest in archaeology and regular local digs; the rise of re-enactment and reconstruction, with the resulting hands-on experience which has created a new body of knowledge; the publication of books dealing with everyday life and the proliferation of accessible TV programmes bringing dead peoples secrets into our homes.

Thankfully, a considerable reassessment of what constitutes history has resulted in a shift in perspective to encompass all aspects of life in the past. No details are off the table, from sexuality and intimate health, to dirty linen and toilet habits. The human experience cannot be understood in its entirety while the daily and mundane are excluded: the shoe that pinches on our walk, the rumbling tummy that prevents us from concentrating, the accidental downpour that soaks us on the way home. This is life. If we understand this, we understand that, like us, the Tudors were also continually experiencing their own physicality, as the basal rate from which every other aspect of life stemmed.

If nothing else, the study of the material world was a study of the human condition, but, more than this, it was literally and metaphorically the building bricks the Tudors used to decode the meaning of existence. It was by cutting up fruit, or human organs, or peering at flasks of urine that doctors formulated theories about the workings of the body. Through the style of a gown or the ornamentation upon a cap a mans social standing was identified, and he might be rejected, or advanced, accordingly. As many Tudor thinkers admitted, there was much in their world that lay beyond the scope of their understanding and the five senses were essential to deconstructing meaning and self-fashioning.

This book is not just a study in material culture, it is a celebration of the experience of being alive in Tudor times. Although significantly more evidence survives for the lives of the upper classes, I have sought out material relating to the lower and middle classes as much as possible, and the lives of ordinary Tudors to contrast with the elite. The Tudors were a very visually oriented culture, so this books section on Sight is, of necessity, the largest, although it is nowhere near as large as it could have been, while the delicate traces of lost smells and sounds have been more elusive to track down. Above all, this book hopes to capture a different aspect of the enduring appeal of the Tudors and explore the physicality of life in the past. It is a time-travel experience on the page, a celebration of what material culture can offer and a box of delights for lovers of the Tudor years.

Amy Licence

Canterbury

PART I SIGHT

PEN AND BRUSH

THE AMBASSADORS

In 1533, the German artist Hans Holbein completed a new work, painted in oil and tempera, upon oak boards cut from English woods. In rich tones of green and red, black and gold, he portrayed two young men, both foreigners in London like himself. They were the 29-year-old Jean de Dinteville, ambassador of Francis I of France, and the 25-year-old Georges de Selve, soon to be Bishop of Lavaur, whose ages are inscribed upon the ambassadors dagger and on the page end of the bishops book respectively. They gaze directly back at the viewer with a mixture of pride and patience, meeting our eyes at a time when the sitters of most court portraits, even members of the royal family, including the king and queen, are portrayed in demure semi-profile. These men are bold. They are cultured and fashionable. They have money. They want you to know it.

Dinteville, who commissioned the work, stands on the left, dressed in the most elegant outfit for an ambassador: a black velvet doublet and pink silk shirt, slashed with white at the chest and wrists. Over it, he wears a heavy coat with puffed sleeves, lined with lynx fur, and the fashionable round-toed shoes of the Tudor court. De Selves colouring is more modest, his long brown gown with fur lining covering a plain black garment and white collar beneath, more suitable to his religious calling. He wields his gloves in his right hand and wears the trademark soft, black Canterbury cap of Catholicism, with its square corners.

THE AMBASSADORS

THE AMBASSADORS