Contents

Guide

Pagebreaks of the print version

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

To the Infinite Mystery of Mysteries, the Great Unseen Force behind all life, the Illuminating Light of the cosmic order, the Wise Mentor, and Wondrous Inspiration of the world-changer

Instructed in the methods of traditional Islamic scholarship yet writing for a popular audience, I had to balance a range of factors to make this biography both grounded in established Islamic sciences and accessible to readers of all backgrounds. My aim has been to harness the wisdom of the ulama (traditional body of Islamic scholars and sages) to provide a humanized understanding of Muhammad and his world.

For ease of readability, I have not included the honorific peace be upon him customarily added after the mention of Muhammads name. Similarly, rather than footnote each fact presented in the text, I have included source documentation at the end of the book.

Arabic transliterations of select consonants (sirat, not zirat) and vowels (Musa, not Mus; and alaihim, not alaihum) are based on the Kufic vernacular and tajwid (elocution) guidelines of Imam Hafs via Asim, which is the popular pronunciation of classical Arabic standardized by the Abbasids in the East (that is, the lands east of Egypt, including the former domains of the Ottomans, Safavids, and Mughals). For certain proper names, I use the standard English rendition: Mecca, not Makkah; Medina, not Madinah; Al-Zahiriya, not Ath-Thahiriyyah; Yemen, not Yaman. Also for ease of readability, I will not accentuate the long vowels or distinct Arabic sounds.

Translation from any ancient language into contemporary English has its challenges. My translations (including Qur`anic passages) draw on the Semitic root meanings of Arabic words, knowledge of what Arabic terms meant in Muhammads era (many have evolved since then), and narrative context to identify the intended meaning among many potential homonyms. I have tried my best to convey the nuances of the original language without the doctrinal interpretations developed in subsequent centuries (which characterize many standard English translations of Qur`anic verses that try to compete with the King James Bible). Translations are based on combining the connotation of passages across Qur`anic variations, known as the Qira`at (expressions, vernaculars). As I explain later, I often use the terms the Divine or Loving Divine for the Arabic word Allahand Divine Mentor or Cosmic Mentor for the Arabic Rabb.

I calculated the specific timing of key events outlined in the book by cross-referencing details from Islamic scholarship with other historical sources, as well as mapping the Islamic calendar onto the modern Gregorian calendar (with CE standing for Common Era). Certain Arabic words that convey nuances related to timing provided additional evidence. For example, diverse verbs pinpoint the moment of action, including: asbaha (at early dawn); yaghdu (at late dawn); ashraqa (at sunrise); adh-ha (in the morning); zala (at noon); thalla (in the afternoon); amsa (in the evening); bata (at night); taraqa (at midnight); and raha (late at night). Clues extracted from language can thus bring remarkable accuracy to events that happened centuries ago.

Finally, as I note in the introduction, Muhammad explicitly instructed that followers focus on his ideas rather than on his life and person. That request, however, was disregarded soon after his death, and the study of his lifesirahemerged as a formal discipline of Islamic scholarship. While this book constitutes one small contribution to that field, I wrote it with mixed feelings, cognizant of the fact that I was invading Muhammads privacy. Muhammad, the historical and spiritual icon, deserves to be better understood, and I hope he will pardon the intrusion.

Mecca: 10:00 a.m., Friday, March 20, 610 CE

The aroma of fresh spices and frankincense saturated the crisp morning air as a striking figure in red and white navigated Meccas marketplace filled with shoppers preparing to celebrate the spring equinox.

The man in red and white stood out amid the crowd, his bold garments defying standard tribal classification in a society where clothing functioned as an identity card. Residents of Arabia declared their clan affiliations via the distinct styles, colors, and shapes of their apparel and the arrangement of their headdresses. Yet the mans color combination matched no established tribal look and suggested instead a fusion of identities, including styles from beyond Arabia.

Friday was supposed to be a time of heightened Arab pride. The Meccans called it yawm-ul-urubah (day of Arab-ness). Its weekly observance reflected Arabias obsession with tribal identity. The market crowd had no idea the man in red and white would one day convert Fridays to yawm-ul-jumuah (day of inclusion).

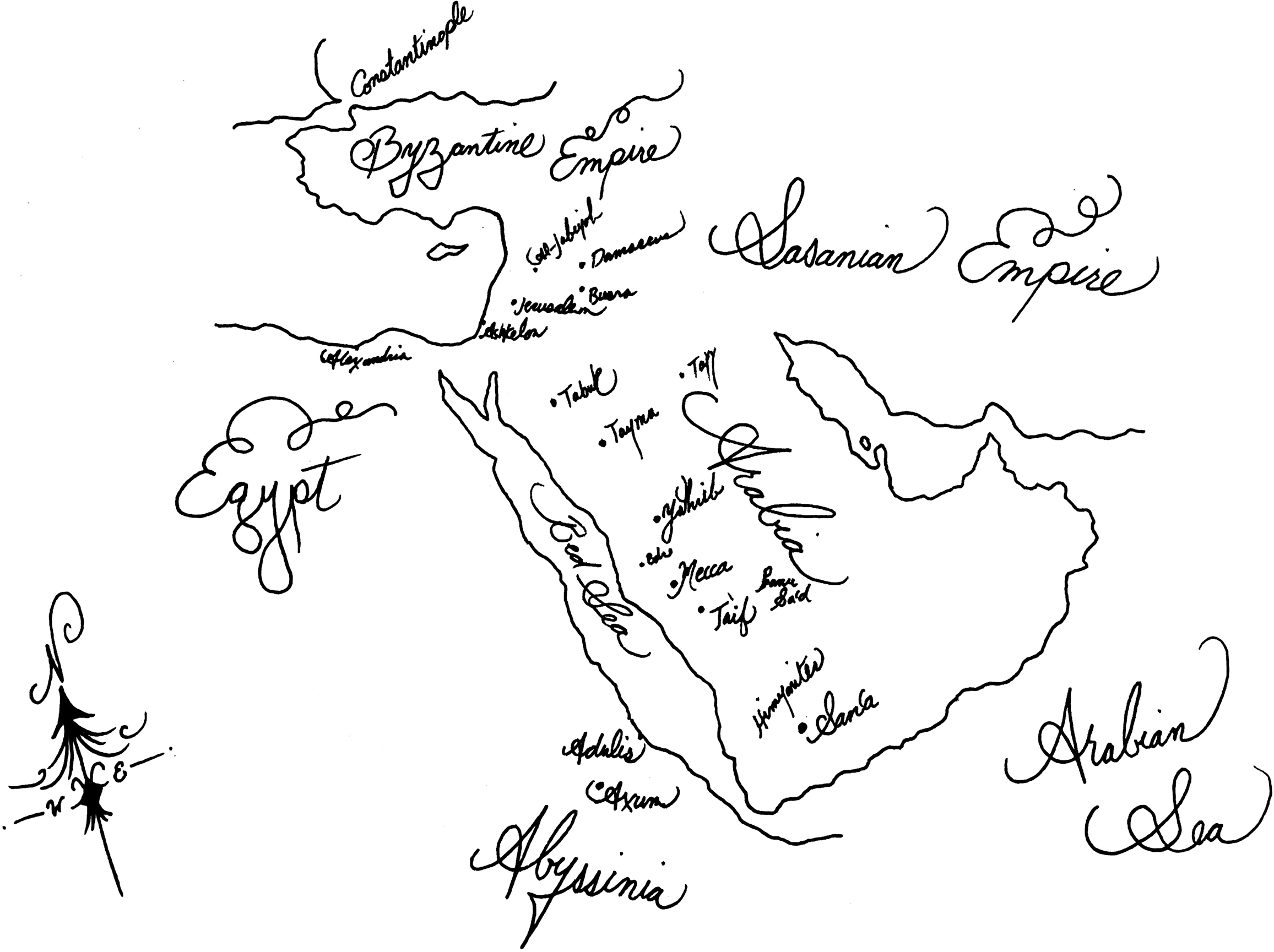

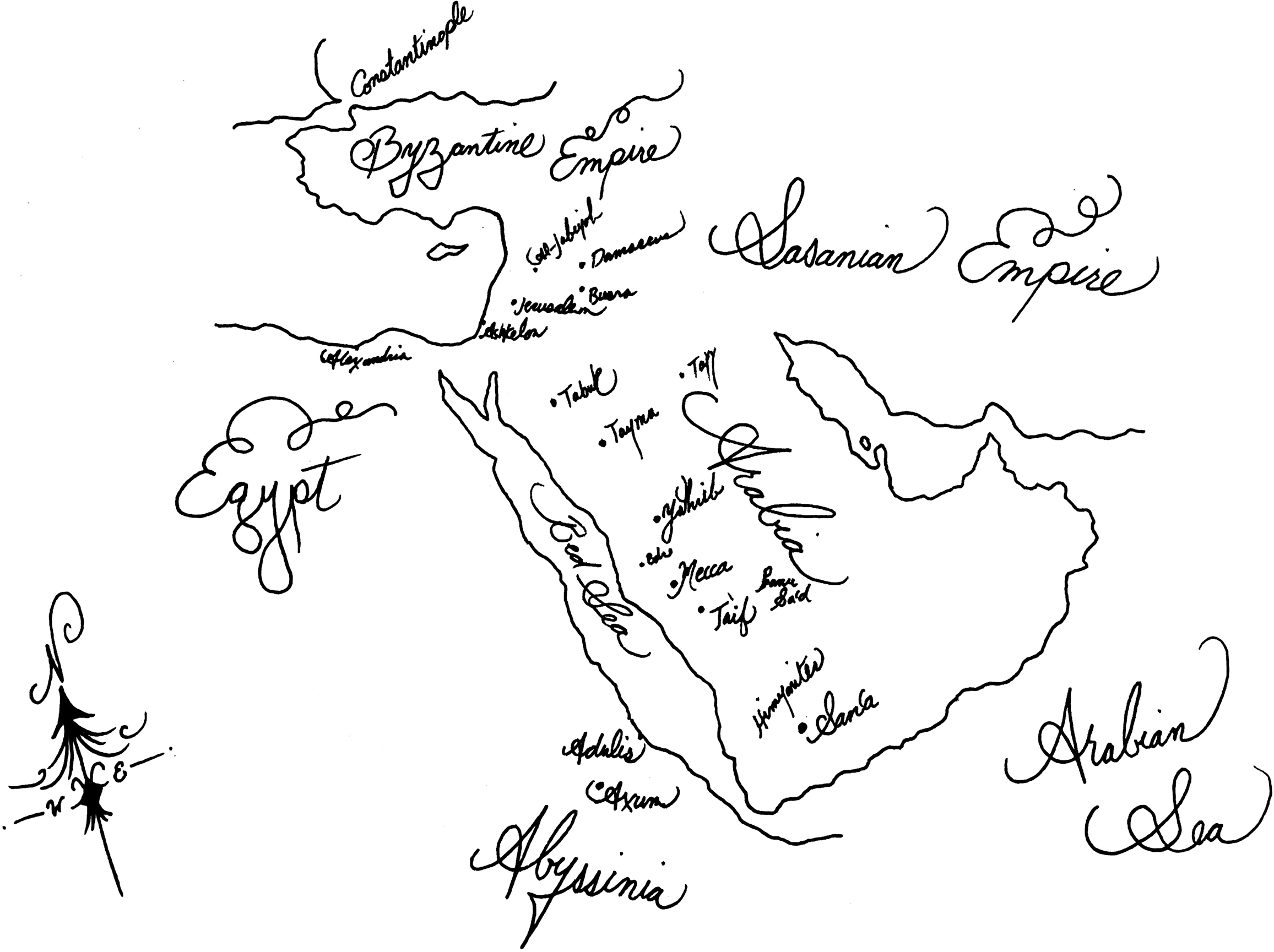

Though Arabs of that time lagged behind neighboring empires in literacy and developmentByzantium, Persia, and Abyssinia far outshone Arabiapride remained central to Arabs sense of self. Their legendary code of honor yielded high standards of generosity and trust. In Mecca, no visitor went hungry, as clans fiercely competed to welcome guests, many of them merchants drawn to trade their wares in Mecca because of the locals reputation for honesty in commercial affairs.

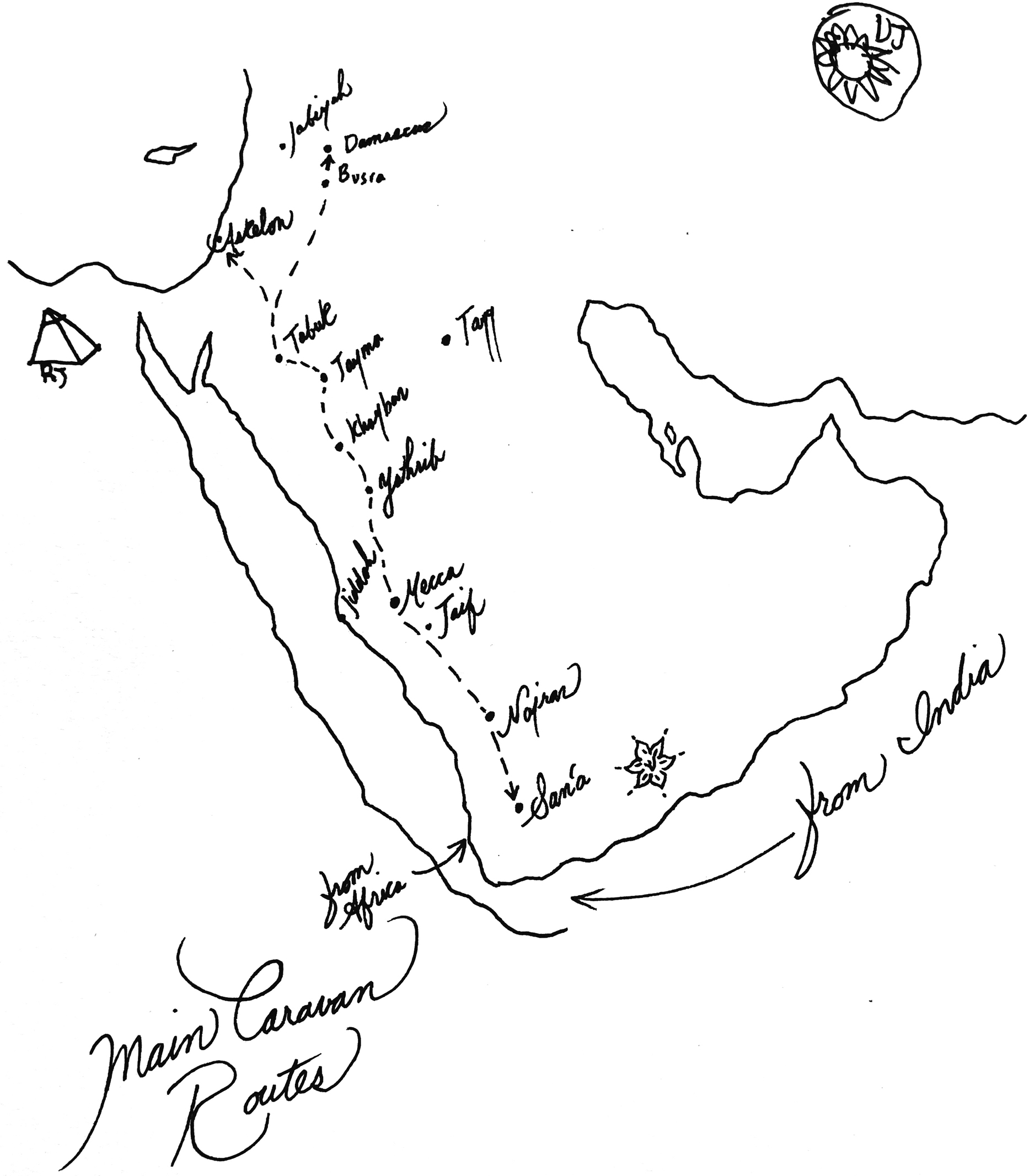

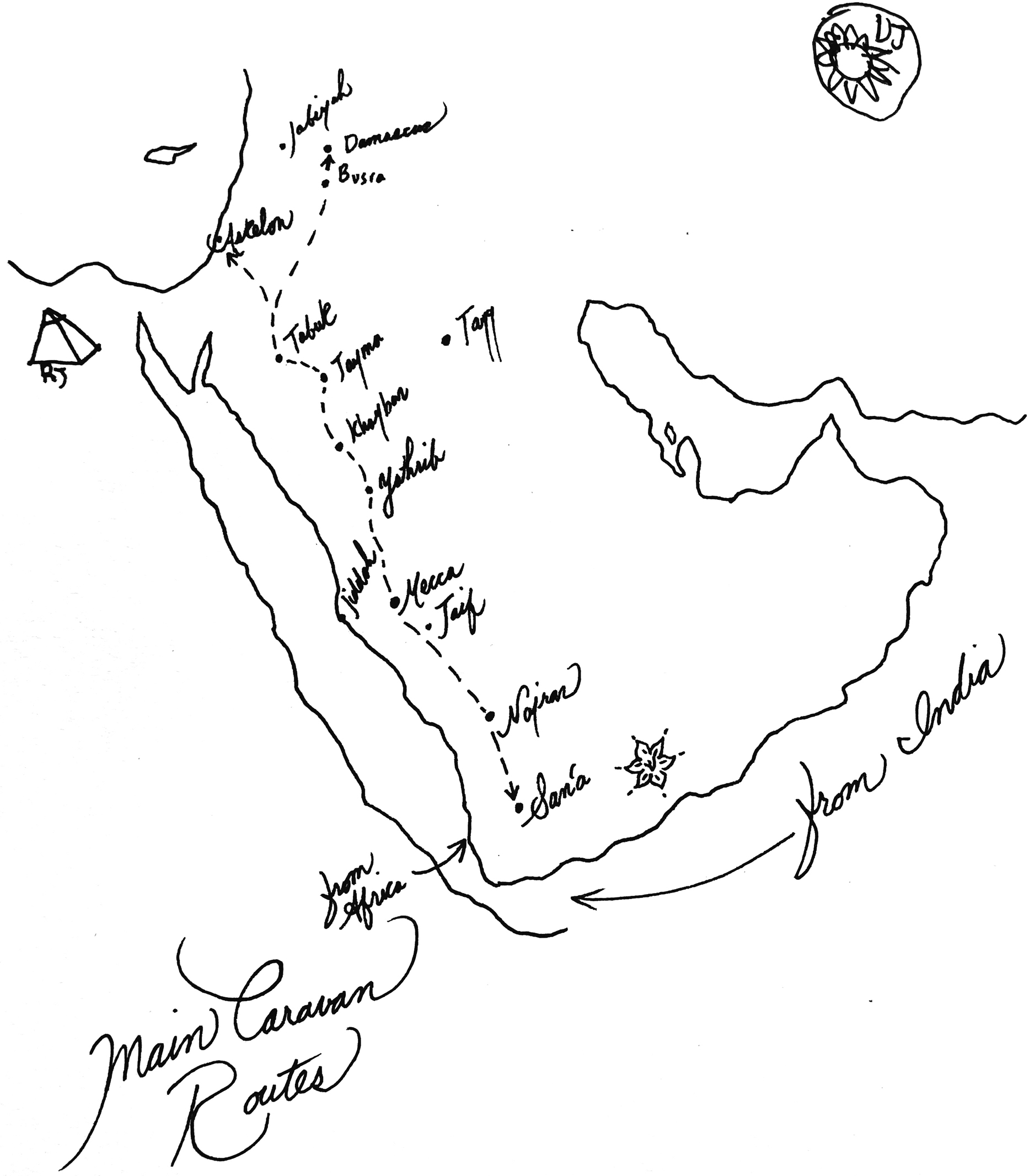

Rainfall had returned at winters end, and the desert flora had begun to blossom. Februarys flash floods had subsided, clearing wilderness pathways for local merchants, who would soon depart on the seasonal caravan north to Syria.

Caravans carrying merchandise and pilgrims now converged on the capital city, heading down largely treeless streets past mud-brick buildings toward an asymmetrical cube construction at its center. Known as the Kabah (nexus), it housed Arabias most prized objects: 360 devotional idols. The shrine, Meccas sole stone building, was managed by priests who permitted only well-dressed wealthy elites inside. Poor pilgrims who could not afford the required fine clothing milled about the Kabah naked. Thanks to the man in red and white, the shrine would one day be transformed into an egalitarian gathering point without gatekeepers or idolsand without special clothing required.