ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Geoff Wills is a former professional musician and clinical psychologist. His large-scale study of occupational stress in popular musicians, Pressure Sensitive, was published in 1988 and he has contributed to International Musician magazine, jazz.com, Psychology of Music and The British Journal of Psychiatry. In 2013 he contributed a chapter to the book Frank Zappa and the And.

Copyright 2015 Geoff Wills

The moral right of the author has been asserted.

Apart from any fair dealing for the purposes of research or private study, or criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, this publication may only be reproduced, stored or transmitted, in any form or by any means, with the prior permission in writing of the publishers, or in the case of reprographic reproduction in accordance with the terms of licences issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside those terms should be sent to the publishers.

Matador

9 Priory Business Park,

Wistow Road, Kibworth Beauchamp,

Leicestershire. LE8 0RX

Tel: 0116 279 2299

Email:

Web: www.troubador.co.uk/matador

Twitter: @matadorbooks

ISBN 978 1785897 993

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Matador is an imprint of Troubador Publishing Ltd

For Judith

CONTENTS

AUTHORS NOTE

The world of popular music writing tends to be partisan. In general, rock writers dont write about jazz, and jazz writers dont write about rock. Of course, there are exceptions: Richard Williams writes eloquently about musicians as different as Miles Davis, Bruce Springsteen, Lou Reed and Duke Ellington, all in one volume, Long Distance Call (2000), and Barney Hoskyns includes excellent sections on West Coast jazz in his book about the Los Angeles rock and pop music scene Waiting for the Sun (1996). Bill Milkowski writes about personalities as diverse as Keith Richards, Wynton Marsalis and John Zorn in Rockers, Jazzbos and Visionaries (1999). But in general there tends to be little cross-fertilization of information, and this is unfortunate, especially when attempting to gain a complete picture of an artist like Frank Zappa. In this book I have attempted to present an example which helps to correct this imbalance.

CHAPTER 1

DID IT REALLY SMELL FUNNY?

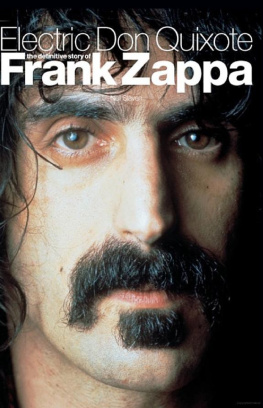

With every year that has passed since his death in 1993 at the age of fifty two, there has been an increasing acceptance that Frank Zappa is an iconic musical figure. His music continues to be played by a variety of ensembles in America and Europe, and at the time of writing, twenty eight Zappa biographies or Zappa-related books are currently available. Although he used the arena of popular music to make his entrance into public consciousness, to class him simply as a popular musician would be to do him a severe disservice.

Zappas music has a unique and easily recognizable quality, and is a brilliant and original synthesis of a wide range of cultural influences, including those of twentieth century classical music, film music, cartoon soundtracks, American stand-up comedy, rhythm and blues and jazz. This book focuses on just one of the influences on Zappas music, namely jazz, and an attempt is made to clarify the often-confusing nature of his relationship with it. From the commencement of his career, and regularly thereafter, his liking for jazz (at least, certain types of jazz), and its influence on his work, was obvious. And yet Zappa liked to give the impression that he disliked jazz. On his album Roxy and Elsewhere (1973) he famously stated that jazz is not dead it just smells funny, and in his autobiography The Real Frank Zappa Book (1989) he included a section entitled Jazz: The Music of Unemployment. In a 1978 interview with Dave Fass in Acid Rock magazine, he simply said I dont like jazz. Possibly his most vehement statement on the topic occurred in a 1984 interview with Richard Cook in New Musical Express:

I was never involved with jazz. Theres no passion in it. Its a bunch of people trying to be cool, looking for certification of an intellectual community. Most of todays jazz is worth less than the most blatantly commercial music because it pretends to be something its not. Id rather stay away from that.

(Cook 1984, 15)

In 2003 the music writer Charles Shaar Murray wrote and presented a programme for BBC Radio 3 about Zappa and jazz entitled Jazz from Hell. In it he took Zappa at his word and stated that Frank Zappa was not a jazz musician and he obviously didnt see himself as one he wasnt even a jazz fan. In the present thesis, I shall attempt to show that this statement is manifestly untrue.

So why did Zappa say that he disliked jazz? In truth what he disliked was not jazz, but the jazz Establishment, just as he disliked every other Establishment, be it that of education, religion, politics, classical music or any other orthodoxy of American society. In this sense, he was a classic outsider. Quite simply, jazz was just one of a long list of subjects that had the capacity to incur his displeasure. One has only to refer to The Real Frank Zappa Book to encounter a continuous flow of irritants, including people (stupidity, not hydrogen, is the basic building block of the universe I dont have friends), the education system (I dont like teachers. I dont like schools), politicians (a bunch of really bad people), musicians (they tend to be lazy, and they get sick and skip rehearsals), the tendency of symphony orchestra members to make mistakes ( made so many mistakes, and played so badly that it required forty edits to try to cover them) and religion (The Cloud-Guy who has The Big Book).

How did Zappa acquire these bleak views? From an early age his experiences gave him good reason to be cautious in his dealings with the world. As Barry Miles (2004) observes, at the end of the Second World War, people did not forget that Italy had been at war with America, and the young Zappa, as an Italian-American, was subject to bullying. Between the ages of five and ten he was a sickly child, and as a youth his appearance was the antithesis of the all-American boy: he told Kurt Loder (1990) that when he was eleven, he weighed about 180 pounds, had big pimples and a moustache. To add to his feelings of insecurity, his father, ostensibly because of his work, had caused his family to move home eleven times by the time Zappa was aged eighteen.

In The Real Frank Zappa Book he says Because of my dads work, I switched from school to school fairly often. I didnt enjoy it I kept getting thrown out of high school I had gotten to hate education so much, I was so fed up with going to school His relationship with his father became strained: I didnt get along all that well with him Mostly I tried to stay out of his way and I think he tried to stay out of mine as much as he could Barry Miles (2004) discusses Zappas father, and suggests that there was an agitated quality in his inability to settle in one job for too long, leading to constant, unnecessary relocation. This had a detrimental effect on his family, who found it increasingly difficult to make an emotional commitment to anything more than superficial friendships in each new setting. The young Frank became withdrawn, inward-looking and wary of letting his real feelings show, and this was a mindset that cast a shadow for the rest of his life. By the time he was fifteen he had attended six separate high schools, predictably affecting his education negatively and precluding entry to a university, even though he was highly intelligent.

Next page