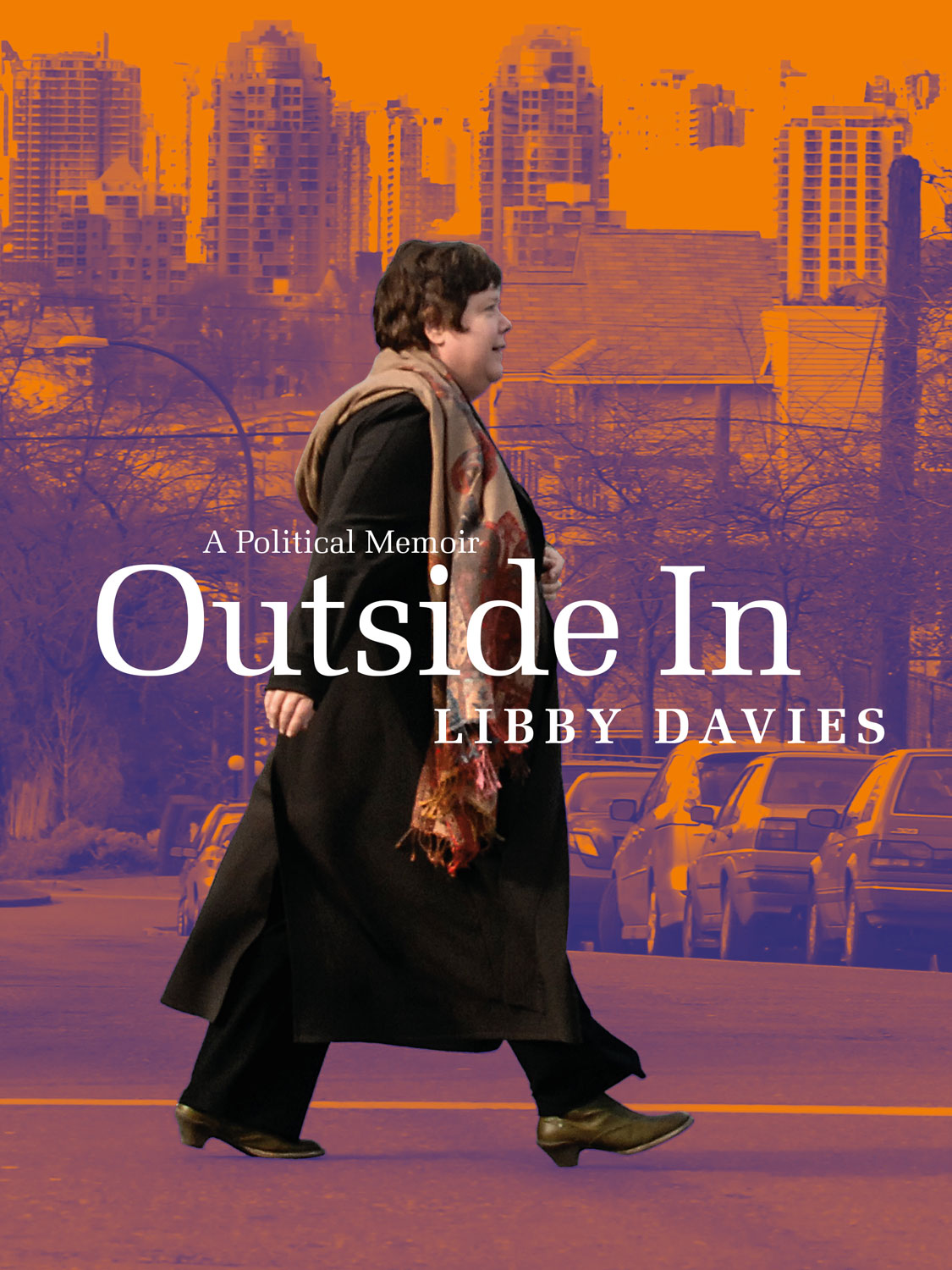

Outside In

A Political Memoir

Libby Davies

Between the Lines

Toronto

2019 Libby Davies

First published in 2019 by

Between the Lines

401 Richmond Street West

Studio 281

Toronto, Ontario M5V 3A8

Canada

1-800-718-7201

www.btlbooks.com

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be photocopied, reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, recording, or otherwise, without the written permission of Between the Lines, or (for photocopying in Canada only) Access Copyright, 69 Yonge Street, Suite 1100, Toronto, Ontario, M5E 1K3 .

Every reasonable effort has been made to identify copyright holders. Between the Lines would be pleased to have any errors or omissions brought to its attention.

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Davies, Libby, author

Outside in : a political memoir / Libby Davies.

Includes index.

Issued in print and electronic formats.

ISBN 978-1-77113-445-3 (softcover). ISBN 978-1-77113-446-0 ( EPUB ). ISBN 978-1-77113-447-7 ( PDF )

1. Davies, Libby. 2. Politicians--Canada--Biography. 3. Canada--Politics and government--1993-2006. 4. Canada--Politics and government--2006-2015. 5. City council members-

British Columbia--Vancouver--Biography. 6. Autobiographies. I. Title.

FC636.D39A3 2019 971.064 ' 8092 C2018-906062-X

C2018-906063-8

Design by Ingrid Paulson

We acknowledge for their financial support of our publishing activities: the Government of Canada; the Canada Council for the Arts, which last year invested $153 million to bring the arts to Canadians throughout the country; and the Government of Ontario through the Ontario Arts Council, the Ontario Book Publishers Tax Credit program, and Ontario Creates.

Prologue

My first official day on Parliament Hill in Ottawa, as the newly elected member of Parliament ( MP ) for Vancouver East, was on September 22, 1997. Green grass stretched out in front of the castle-like buildings and the Peace Tower with its Big Ben look-alike clock. It was a beautiful, sunny day, but even so the heavy humidity was so unlike the fresh coastal breezes I was used to. Julius Fisher from BC s working TV followed me onto the Hill to record my first moments. An anti-choice rally on abortion was taking place, and I felt angry about it. Why did they of all people have to be here, I thought. The clock chimed eleven and it dawned on me that I was late. As I picked up my pace, Julius stopped me and said, Libby, waithow do you feel about being here on this first day? What would Bruce think about you being here?

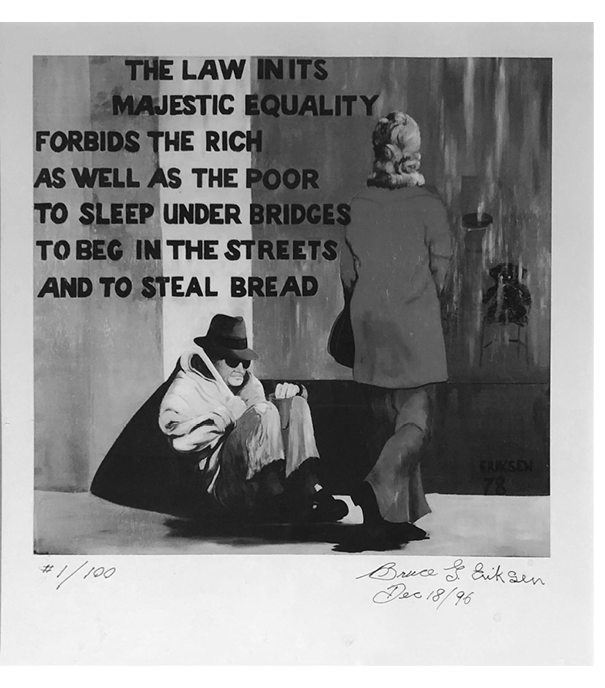

What would Bruce think? Immediately tears came. I wanted to turn and run back to my son, Lief, and the life I had known, even with the staggering absence of my long-time partner Bruce Eriksen, who had died just two months earlier. I got a flash of our lives together, as activists, as community organizers, as city councillors, as co-conspirators, as parents. A sweet team of two that was no more. And now I was far from home and far from the activist life I knew. What the hell was I doing here?

I have no idea what I said to Julius and his camera. I could only focus on cutting through the anti-choice rallythe shortest routeto make it into the House of Commons in time for the election of the Speaker, the first task of any new Parliament after an election. I dreaded meeting the New Democratic Party ( NDP ) caucus, most of whom were strangers to me. I felt lost and not up to the job ahead of me. It was a familiar feeling: one of being thrust into something that I felt unprepared and unqualified for. Yet I knew that people were counting on me to do important things in Ottawa.

My biggest challenge, since my earliest experiences of running for public office, had always been overcoming my own sense of inadequacy. It was almost as though Id gotten where I was not by choice but by accident. But there was another part of me too, the fearless part that was able to push past the uncertainty, driven by a mission, by everything I believed in about making a better society for people. That day on Parliament Hill, my passion for social justice prevailed again. I forced back the tears and strode forward.

Organize, Organize, Organize

In the 1970s Vancouvers Skid Road was a no mans land. Overshadowed by the downtown Central Business District, it didnt appear on civic planning maps. No one at city hall cared about the area. Its seven thousand plus residents were left to the mercy of numerous churches, charities, and missions as they administered to the poor. To an outsider it seemed a bleak and unforgiving place, derelict in both its physical and human form. The blocks of battered, broken-down brick and wood hotels and rooming houses, built mostly at the turn of the century, with decades of soot and grime on dirty grey windows, overlooked heavy traffic arterials leading into the downtown core. It was an area of forgotten old men who were seen as down-and-outs that the city would rather ignore.

Just a block away lay Gastown, the historical centre of the modern-day city. It, too, was part of Skid Road, with heaving brick streets, old rooming houses and hotels with beer parlours containing single-room occupancies ( SRO s), and the Gassy Jack statue standing guard. But by the 1970s it had mostly been bought up by developers with dreams of cruise ships and happy tourist spaces. It was an uneasy co-existence for the remaining low-income residents, feeling unwelcome in their own community, next to wary tourists looking for a good souvenir.

Today, some fifty years later, although some of those rooming houses still exist and people still call them home, thousands of rooms have been lost to gentrification and thousands of people have been dispersed like parcels to lost addresses. The need for permanent social housing is as urgent now as it was in the 1970s. It seems unbelievable, but those critical housing issues persist due to decades of chronic austerity programs and unrelenting income inequality in Canada. Still somehow the neighbourhoodfor it is a neighbourhood in every senseand its community of survivors and brave souls continue to survive in a city of glass towers and flowing wealth that takes care only of itself and no one else.

My introduction to Skid Road came through a federal Opportunities for Youth summer student employment program. I applied to help establish a low-cost food store in the recently established community health clinic. I was a student at the time, and that summer of 1972 was a life-changing experience that immersed me in what was to become the community of the Downtown Eastside and a lifetime of work.

The idea of setting up a low-cost food store in Vancouvers inner city was a simple one: buy food in cheaper large quantities from local wholesalers, and resell at cost in small units so that residents of the community had better purchasing power for their below-the-poverty-line incomes. You want only six tea bags? We could do it. One cup of soup mix, or one can of sardines, one tomatoit was there. The food store was just a makeshift counter upstairs in the health clinic, with some roughly fashioned shelves displaying the basic food wares for sale. Thus began my work at age nineteen, as a community organizer in what was still called Skid Road.