Table of Contents

Guide

Page List

Contents

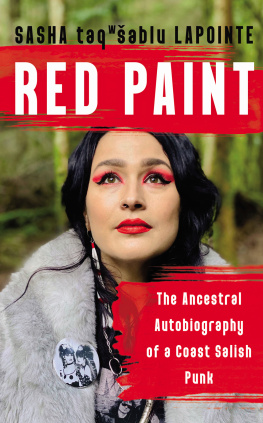

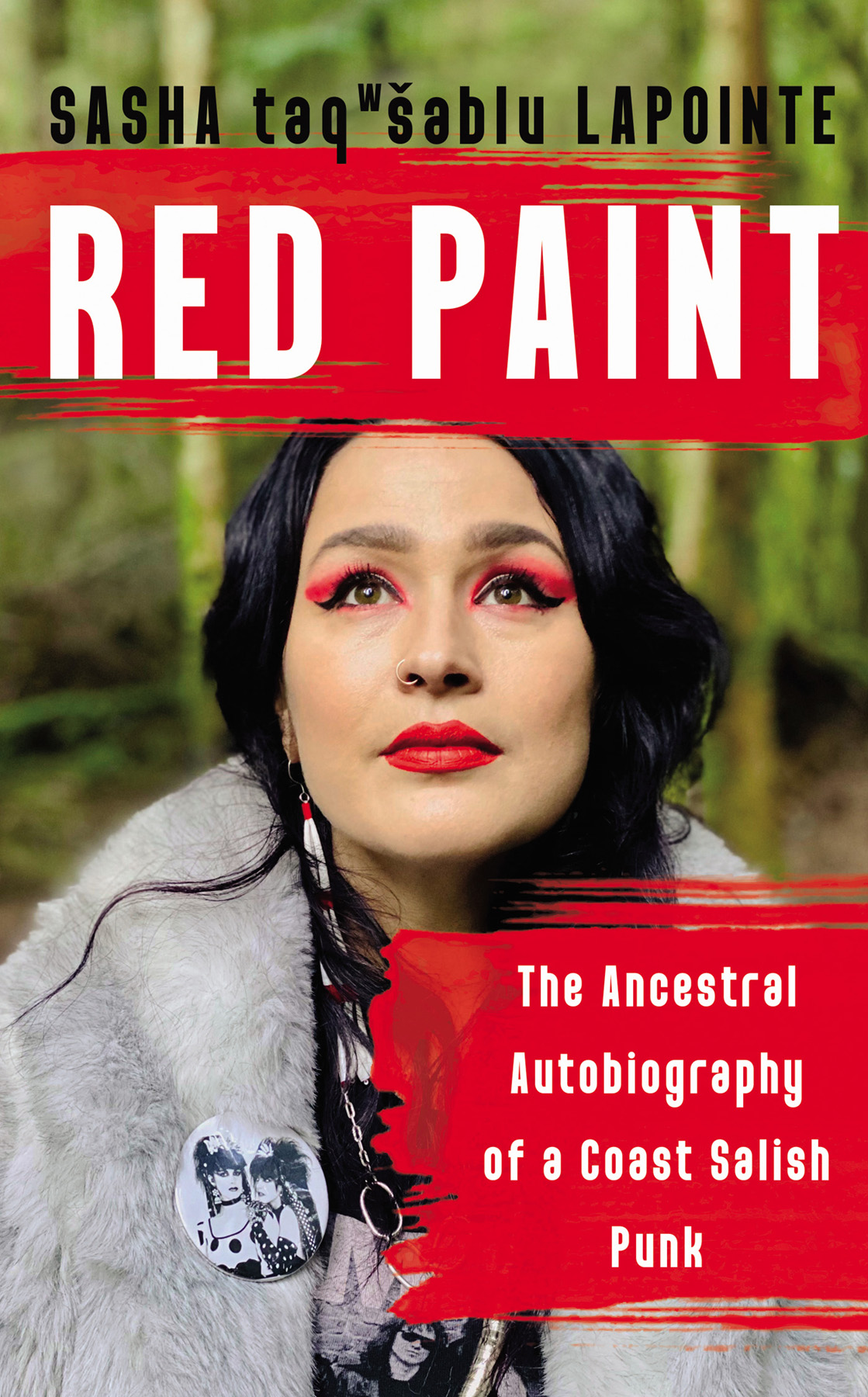

Red Paint

Copyright 2022 by Sasha taqsblu LaPointe

First hardcover edition: 2022

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission from the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: LaPointe, Sasha taqweblu, author.

Title: Red paint : the ancestral autobiography of a Coast Salish punk / Sasha taqweblu LaPointe.

Description: First hardcover edition. | Berkeley, California : Counterpoint Press, 2022. | Authors name is spelled: Sasha taqw[schwa]blu, the e in her Coast Salish name in all instances the e should be a schwa, an upside down e and the w is written in superscript. Publishers email.

Identifiers: LCCN 2021029010 | ISBN 9781640094147 (hardcover) | ISBN 9781640094154 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: LaPointe, Sasha taqweblu. | Coast Salish IndiansWashington (State)Biography. | Salishan womenWashington State)Biography. | Coast Salish IndiansHistory. | Coast Salish IndiansSocial life and customs. | Punk cultureWashington (State) | Psychic traumaWashington (State) | Resilience (Personality trait)Washington (State)

Classification: LCC E99.S21 L36 2022 | DDC 979.7004/97940092 [B]dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021029010

Jacket design by Nicole Caputo

Book design by Jordan Koluch

COUNTERPOINT

2560 Ninth Street, Suite 318

Berkeley, CA 94710

www.counterpointpress.com

For the women who came before me, and for Violet

Red Paint

If you look at the cedar

bil cx gsuuc ti xpay

youll see how it bends

c()xa sudx scal ki suqcil

and doesnt break

gl xi gsux

and you have to learn how to be like the cedar,

gl yaw cx lhadx scal k(i) adsshuy

sist ti xpay

how to be flexible and pliable

scal ki ssqcil gl (s)spil

and you yourself will not break.

gl xi ki g()adsux.

Violet taqsblu Hilbert

(Translation requested by Sasha taqsblu LaPointe

Translated by Zalmai swli Zahir, March 11, 2020)

Transcribed and translated by Violet taqsblu Hilbert, from gqulc/ Aunt Susie Sampson Peter; the Wisdom of a Skagit Elder

I was sick, I was sick for a long

time. Spiritually, supernaturally

ill.

For the entire salmon season, during all of the

runs. We caught humpback salmon first.

We killed them. Indeed we killed them.

As a consequence, it seems the salmon took

me. They ran off with me (my soul).

There I was sick.

I was medicated (treated) yet I became progressively

worse. It took place there on the Skagit River.

There I lay (for an indefinite time) until the salmon run

finished. I became very thin.

My stomach was

compressed. No food was

inside.

I was skinny.

When I would feel it, my face was only bone.

Then I dreamed! I dreamed! I overheard talking,

Oh you folks had better return that human

woman. You should return her to her human

world.

You, the one called skaysliw, will return her.

The leader with a great big canoe was thus

identified. Many other people were on board.

With their red paint

and cedar bark headdresses on.

I was traveling on the back of a

salmon. That is how I was canoed.

I was very afraid that I would fall off and drown.

Then I overheard in song:

Unload her now, skaysliw,.

You have arrived back in your

land. You will disembark.

You will say to your own grandmother, Open the door for

me. I came back.

I walked upland, I knocked on the door.

Open the door, Grandmother. I have arrived.

But they said of me I was crazy (confused, they said).

Grandmother said,

Get a grip on yourself, for you did not just

arrive, my dear little one,

you have instead always been

here, asleep continuously and

dreaming.

We were a hunter-gatherer society. We were nomadic. We lived along the coasts and on the rivers. We moved with the water. We moved with the resources and followed the supply of fish. We picked berries and bracken root. We wove garments out of cedar, and mats for sleeping out of cattail grass. Shellfish and salmon were important to us. We lived in cedar plank houses. We lived communally.

And we held winter ceremonies. In the longhouse, people gathered. They built a great fire, they banished spirits in an opening ritual, and then they danced. They danced to the pounding of drums. On dirt floors, with bare feet, with smoke thick in the air, my ancestors danced until dawn broke.

When the missionaries arrived, they banned the Coast Salish peoples spiritual practices.

So ceremonies went underground and for the first time were held in secret. Treaties were passed and eventually the Salish ancestral religion was given back to the people, but now it was something protected, something private.

It is not my job to tell the story of what happens in the longhouse. It would be considered disrespectful. My mother has taught me to behave a certain way, to honor and uphold our traditions and the wishes of my elders. We come from a long line of Salish medicine workers. We respect this. What happens in the longhouse is not what this story is about, but this is a story about healing. This is a story about what Ive learned from my ancestors. My ancestors participated in the winter dances.

They wore red paint.

There is a word that hangs next to the front door of my parents home. Written on an index card in black ink it reads hdiw. It is the Lushootseed word for come in. It welcomes me. Every time I see the sign, I sound out the word and wonder if I am saying it wrong. Hu-dee-ew. I have never learned to speak our tribes traditional language.

On a rainy afternoon in midsummer, I walked up the road to visit my parents. I had a question to ask. I came to the door, the word and I had our ritual, then I punched in the security code: 1-4-9-2. Really, this is the code. Sometimes its easier to remember the hard things. The year Columbus discovered America clicked the mechanism unlocking the front door and letting me into my familys home. Ive often wished I understood the technology well enough to program 1-4-9-1.

It is a small house. Small and old. And it has been in my family for generations. It sits on the large slope of a yard, on a hill that looks out toward Mount Tahoma, which like my parents lock combination has also been colonized, renamed after a white admiral. Now this mountain is known as Mount Rainier. On some of the old maps of Tacoma, you can still see the lines that border this area of the east side, labeled INDIAN ALLOTMENT LAND . This is the reservation. The river is polluted. There are no grocery stores in walking distance, but from the hill we can see downtown. We can look out at the Salish Sea. A white friend once told me he moved his family away from Tacoma because he wanted to have a garden. He wanted to teach his young son how to grow things and he told me, You cant do that here. The soil is bad.