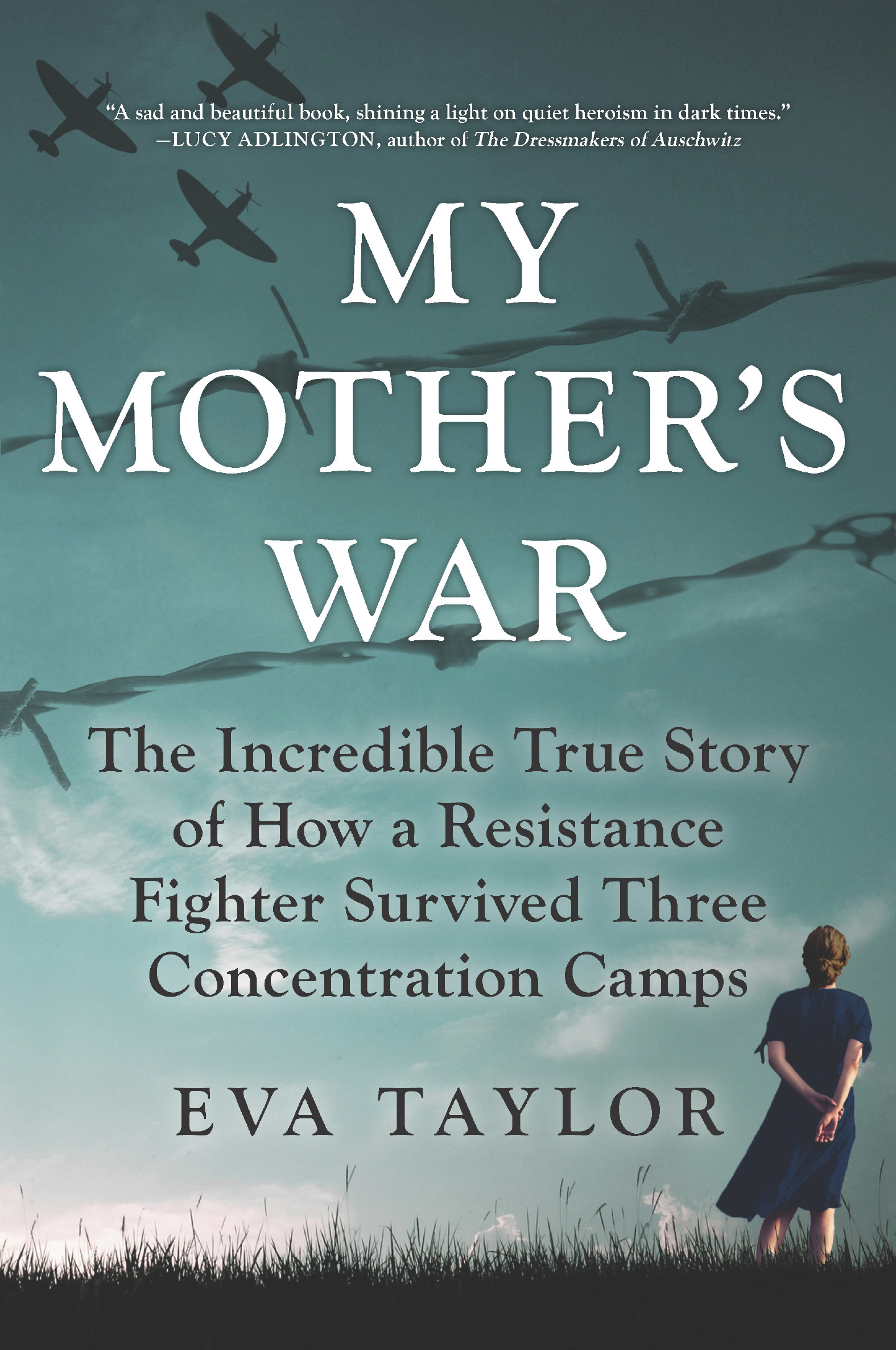

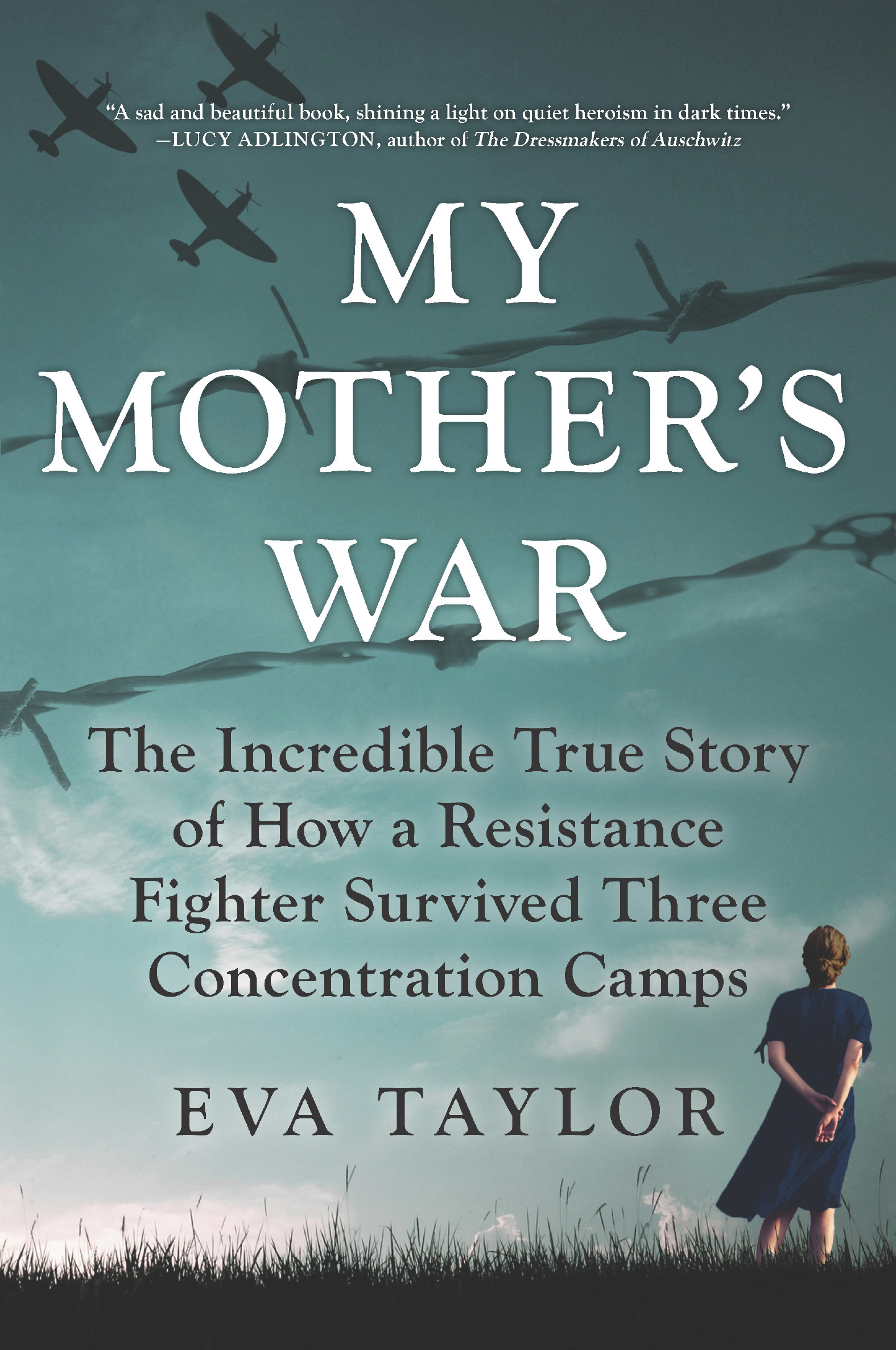

Praise for My Mothers War

There may be many hundreds of tales of resistance and resilience in World War Two, but there is something special about this haunting story, crafted from a poignant family archive. My Mothers War unfolds in a calm yet relentless manner, drawing the reader into the reality of Nazi occupation and imprisonment, as well as offering reflections on how life could have beenshould have beenfor all innocents caught up in war. A sad and beautiful book, shining a light on quiet heroism in dark times.

Lucy Adlington, New York Times bestselling author of The Dressmakers of Auschwitz

Here is a daughters compassionate examination of the pain her mother kept so carefully hidden. Taylor is acutely perceptive... This story of one womans courage reveals the complexity of relationships it took to survive three concentration camps. My Mothers War is an important contribution to the work of bearing witness.

Gwen Strauss, award-winning author of The Nine: The True Story of a Band of Women Who Survived the Worst of Nazi Germany

My Mothers War is a very personal but truly captivating story... The cache of letters discovered by Eva Taylor describes in heart-breaking detail the persecution, oppression and deprivation Sabine endured, and brings an authenticity to the story that more dispassionate accounts of the war can never achieve. Its a compelling read that will appeal to anyone who has an interest in true WWII stories.

Doug Gold, internationally bestselling author of The Note Through the Wire

I absolutely loved this amazing story of courage and survival. This book is heartbreaking and heartwarming at the same time and I found it difficult to put it down. Highly recommend to anyone who enjoys beautifully written war time memoirs.

Lana Kortchik, bestselling author of Daughters of the Resistance

My Mothers War

The Incredible True Story of How a Resistance Fighter Survived Three Concentration Camps

Eva Taylor

To Karen, Michael, James, Tjarda, Derk and Theta.

In memory of your Oma.

Eva Taylor is the daughter of Sabine Zuur and Peter Tazelaar, a major Dutch resistance fighter and spy. She was born in Utrecht but has lived in Cheshire, England, ever since she was eighteen.

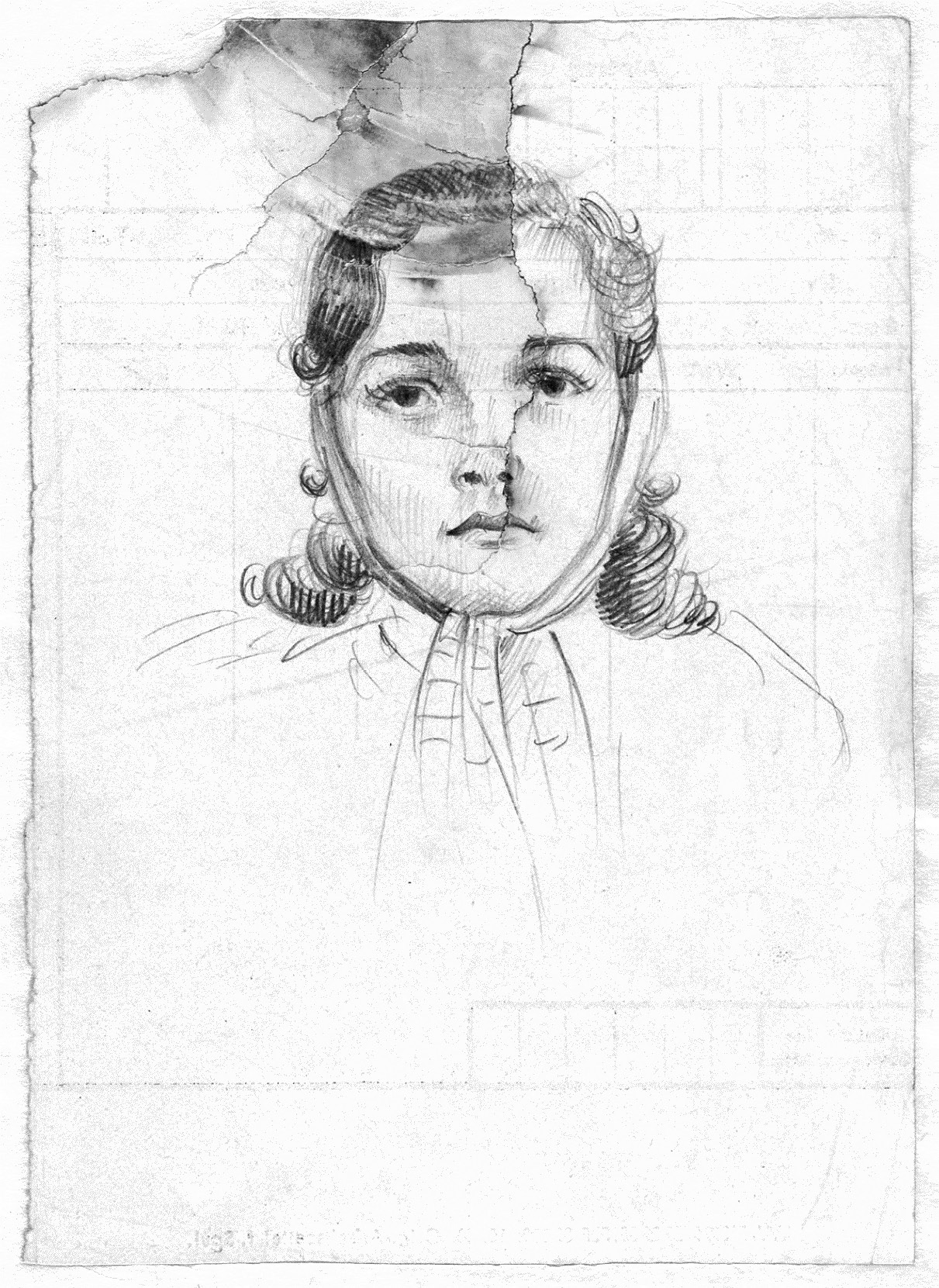

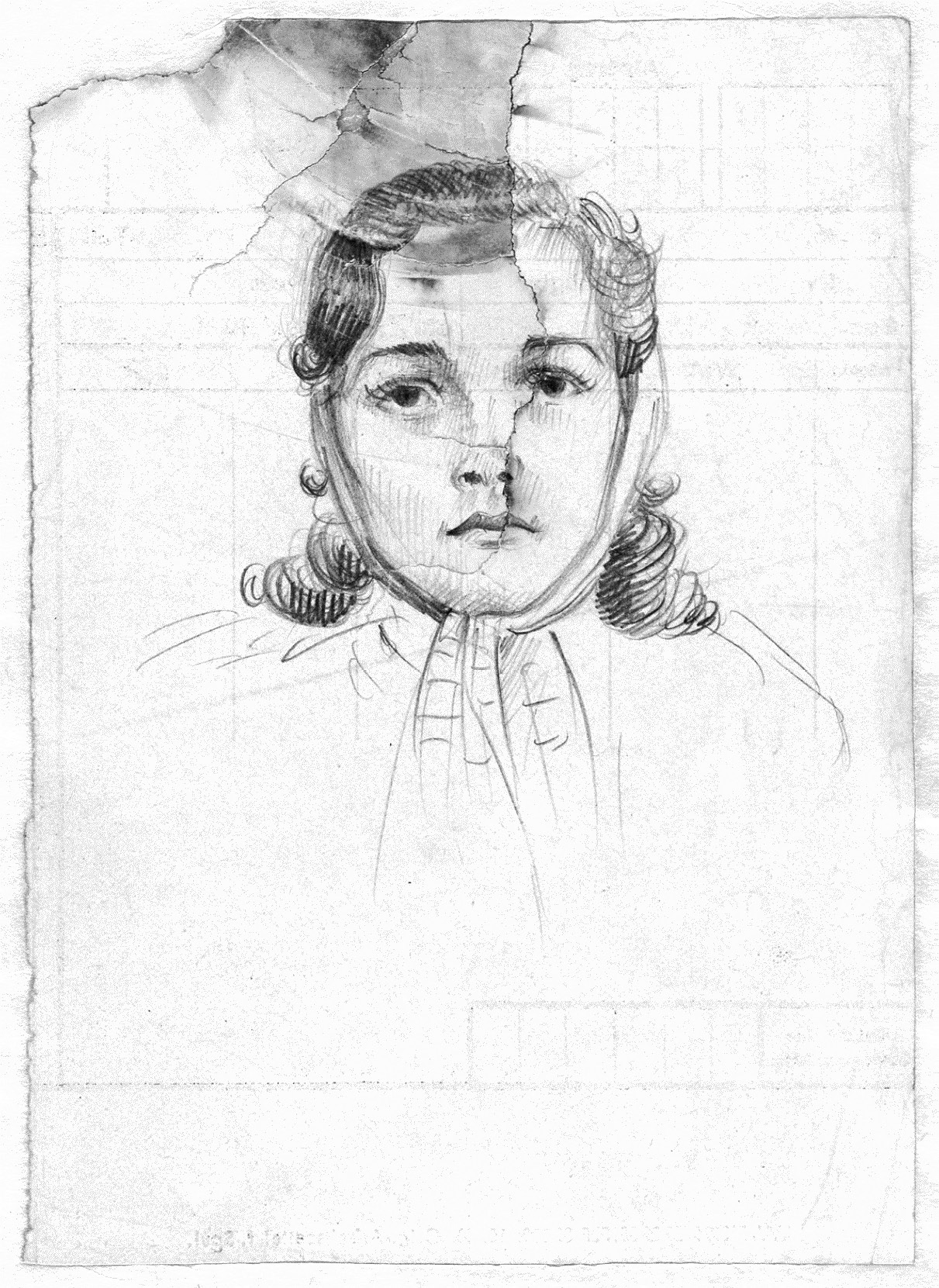

Courtesy of the Rijksmuseum collection

A drawing of Sabine Zuur by fellow prisoner Aat Breur in Ravensbrck concentration camp, Winter 1944.

Contents

Preface

When I visit my mother in the care home, she no longer has any idea who I am, but she is always delighted to see me. When I tell her I am her daughter, her face lights up, and she says, with wonder, I did not know I had a daughter, but you are so lovely. She is by now in her early nineties, almost deaf and blind. Once every six weeks or so, I travel from England to Holland to visit her, and this short conversation is repeated endlessly during my visits. She is happy I am there, whoever I am.

She is settled in the home where she now lives and particularly enjoys the musical afternoons once a week. She always loved dancing, and in her confused state, it seems to be the only thing that she has not forgotten. As soon as the music starts, she jumps up and dances elegantly through the room with a happy smile on her face.

It reminds me of when we danced together when I was a child. During our evening meal, the radio often played nice music, and when she heard a favorite song, she would pull us out of our chairs to dance around together.

I often try and remind her of things in the past, but its only when I go back a long way and talk about her brothers, who died decades ago, that she starts remembering. I sometimes ask her if she remembers the war and little bits come back to her. She tells them to me in a conspiratorial way, like a child who has been naughty.

Although she often talked about the war when I was young, it was always about food, about friends she lost, but never about life in the camps. This is probably because I never wanted to know about it, and perhaps she also could not bear to recall those memories. The horrors have no meaning when you are a child. But now, when it is too late, I am interested.

In her descent into Alzheimers, she has become a loving, caring, kind person. A mother I suddenly love very much. Not at all the mother I knew as a child, and it made me realize how lifes events really can shape you into a totally different person. Id like to think that as her mind leaves this world, her personality seems to revert back to the child and young woman I have read so much about.

When she died in 2012, I found boxes and boxes of letters, photos and documents, mainly about her time in the war. I think I knew her well enough to appreciate that she hoped I would be interested in all this information. In enclosed notes, there were pleas not to just throw it all away.

Her story of the camps is similar to thousands of others, yet different. Some stories are well-documented, but for the many who died without leaving a trace, there are no stories to pass on. And those who found it too painful to tell their stories themselves are now often having them revealed through their children and grandchildren.

Sabines story is but one very small piece in this horrendous period of history, but it is still important to pass it on to future generations, especially her own family.

It is only by reading through all her documentation that I begin to understand her peculiarities, and also discover the person she might have been if war had not intervened.

This is the story of Sabines war.

The Hague

After the War

I grew up in a small second-floor flat in The Hague. I was four when my parents and I moved there, and my earliest memories are of playing in the ruins that surrounded our block of flats, an area heavily bombed towards the end of the war and not yet rebuilt in the early 1950s.

Other memories from that age are also vivid. Not long after we moved, I spent a long time in the hospital, and when I came home again, I remember I was suddenly presented with a younger brother, who appeared from seemingly nowhere. No one told children much about such matters in those days.

Life after the war was difficult for everyone. There was still not much food around, and I remember sweets and fruit were real treats. Winters were so cold my mother put horse blankets in front of the windows to keep the frost out. We had two small stoves in our flat, which were only lit if we had coal. It is hard to believe now that the coal man came once a week with a horse and cart carrying his deliveries of coal, wood and paraffin.

They were lean years just after the war. How lean I only realized once I had grown up myself.

I was always aware, though, even when young, that my mother seemed different from other mothers. She had no money, and yet she was always beautifully dressed and so glamorous. She seemed to have an indefinable aura. My friends, young as they were, were in awe of her. People seemed to go out of their way to help her.

But I also knew another side of my mother. One she never showed to the outside world. She often cried and spent most days in bed with the blankets over her head, leaving us in the care of her cleaner, Tante Cor, who came several times a week to help out (mostly unpaid, I later learned). Nighttime was obviously very difficult for my mother. Perhaps nightmares haunted her, as she usually only got up when everyone else went to bed, and then she would roam around the flat until the early hours, much to the annoyance of the downstairs neighbors, who would bang on their ceiling with a broomstick. But despite this sad side of her, there were plenty of girlfriends around, and she never lacked male attention. On evenings when she went out, she would be at her most glamorous, and no one would guess she had a care in the world. I loved seeing her dressed up and smelling her perfume.

Next page