Introduction

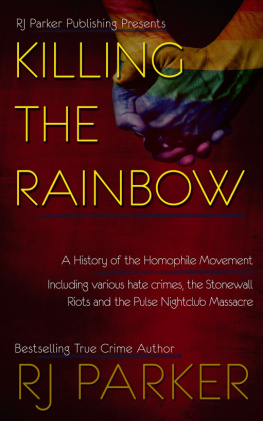

The rights that the LGBT community have gained and continue to gain, from marriage equality to employment nondiscrimination, are the result of decades of hard work from individuals who in the early days, most of the time, lived off the kindness of friends. In the 1960s, being a gay activist was not a profession; it was an unpaid job for those dedicated to LGBT equality. When the newly energized gay movement sprouted from the Stonewall riots of June 1969, there was no organizational support with deep pockets, bailing people out of jail. Those of us in the riot didnt have any best practices or contingency plans to fall back on. The only gay person I knew who was receiving a modest stipend was Reverend Troy Perry, who was building the gay-friendly Metropolitan Community Church.

Thanks to the early activists, today the LGBT community is represented in every segment of American society: from Fortune 500 CEOs, to leaders in education, labor, public safety, and politics, including at the White House. The Obama administration has appointed out LGBT individuals in almost every capacity at the highest levels of government.

We were able to get here because of the tireless work of pioneers such as Frank Kameny, Barbara Gittings, Harry Hay, Del Martin and Phyllis Lyon, Randy Wicker, Reverend Troy Perry, Martha Shelley, Marty Robinson, many of my brothers and sisters in New Yorks Gay Liberation Front, and so many others, including a man named Henry Gerber, who in 1925 created the first LGBT organization in the nation in Chicago.

Since we had no funds, we had to be creative in our efforts to change individuals minds about who we were. This is my story but it is also an American story, one that illuminates and documents the historic LGBT struggle for equality. In most cases, Ive kept to a chronological narrative, but sometimes, as is typical for me, I go off and explore issues that deserve further discussion and attention.

Chapter 1

The Boy from the Projects

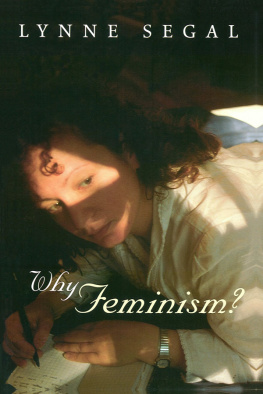

I was an outsider from the beginning. When I was born in 1951 to Martin and Shirley Segal, my father was the proprietor of a store in South Philly, one of those neighborhood groceries that were once common throughout the big cities; in New York they are called bodegas. His proprietorship was short-lived. Against the backdrop of row homes and big Catholic churches, my fathers store was condemned by eminent domain to be replaced by a housing project. My parents, with two little boys and no work, were provided for by the city. At some point, we moved to nearby Wilson Park. There, as a member of the only Jewish family in a South Philadelphia housing project, I got an expert lesson in isolation. Kids who lived there said that we were from the other side of the tracks, and it was a reality since the housing project was sandwiched in on one side by an expressway and on the other by the 25th Street railroad bridge. We were, literally, across the street and an underpass away from a middle-class, mostly Catholic neighborhood.

We were poor, which in the Jewish community is almost a sin against God, or in our case a sin against the rest of the family. To them, living in a housing project was almost unimaginable. Our relatives either turned up their noses at us or pitied us. We were the lowest rung of the family. I was ashamed of my address, 2333 South Bambrey Terrace, of wearing the same clothes until they wore out, of our lack of money, and of every other characteristic of being poor.

Our new neighbors were hardly welcoming. I still remember the first few days of kindergarten when Irish and Italian kids would say to me, You killed our Christ, or the one that always stumped me, Youre a devil with horns. Somehow I became a deformed six-year-old murderer. For a while Id subconsciously touch the top of my head, waiting for the horns to grow, and I wondered, How could I possibly comb my hair with horns?

The only support system I had were my parents, whom I adored and who adored me. They followed the Jewish tradition, knowing that their central obligation as parents was to love their children and to tell them theyre the greatest people in the world. They did that well. I knew I was loved and I knew I was smart. I also knew that I could face the world armed with those two gifts. After all, what else did I have? They gave me the strength to persevere.

My father taught me to be quietly modest, although I occasionally (note: always) broke that rule. I knew my father had been in the war, that he had a Purple Heart, and that his plane had been shot down over the Pacific. Thats all I knew until he died and I went through his papers. He was a war hero who would only say to us, I have a fake knee, its platinum and its more expensive than gold. When I die, dig it out and cash it in. Neither he nor my mother would talk much about those times or about their grandparents, my great-grandparents, who died in the Holocaust.

One time my mother went to my grade school to defend me because the teachers had demanded that I sing Onward, Christian Soldiers. In those days there was still prayer in public schools, and they had us sing Christian songs. I didnt know why I didnt want to sing that song, I just didnt. My teachers couldnt, or more appropriately were unable to, force me to utter a word. Hence, my mothers first of many trips to the school. Of course, that made everyone in Edgar Allen Poe Elementarystudents, teachers, and principalshate my guts. The compromise on the hymn was that I was to stand and be silent while everyone else bellowed out that they were marching off to war. So I knew discrimination from a very young agefrom my affluent extended family, from the people around me in school, and even from the poor people in the project where I lived, who had their own noneconomic reasons not to like me. My refusal to sing Onward, Christian Soldiers was my first political action, my first defiance of conformity and the status quo.

Kids growing up in Wilson Park knew to make friends only with other kids in the neighborhood, not the kids across the tracks. My friends included my neighbor Barbara Myers, the only girl who would communicate with me. She was a slim blonde with buckteeth, glasses, and an unfortunate early case of acne, which never seemed to go away. This made her a fellow outcast, so we had a mutual bond. Mrs. Myers didnt take to the idea of her daughter having a Jew for a friend, but since I was the only one Barbara had, she tolerated me. Barbara eventually became my first sexual relationwell, Im not sure thats what youd call it.

Sexuality to my generation arrived in the form of the Sears, Roebuck catalog. That book showcased almost any item that was necessary for the household, including clothing. Every boy waited for the new edition to arrive, and when it did, the first page he turned to was the one with womens lingerie. Lets get this straight: they werent drag queens in the making searching for an outfit, but normal prepubescent boys looking for their first sexual thrill, and they found it from the various models posing in bras and panties. That didnt really work for me. Actually, the only reaction it stirred in me was to make commentary on color choices. I would think, Gee, she might look decent if that dress was another color. What really worked for me was the mens fashion section. My eyes were glued to the men in underwear.

There was no name for it, at least none that I knew, but somehow it seemed wrong that I was looking at the men in the catalog. After all, men were supposed to be eyeing and sizing up women. I decided to try it. And thus, my first foray into heteronormativity began. Lets call it an experiment.