Barajima Books 2020, all rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted by any means, electrical, mechanical or otherwise without the written permission of the copyright holder.

Publishers Note

Although in most cases we have retained the Authors original spelling and grammar to authentically reproduce the work of the Author and the original intent of such material, some additional notes and clarifications have been added for the modern readers benefit.

We have also made every effort to include all maps and illustrations of the original edition the limitations of formatting do not allow of including larger maps, we will upload as many of these maps as possible.

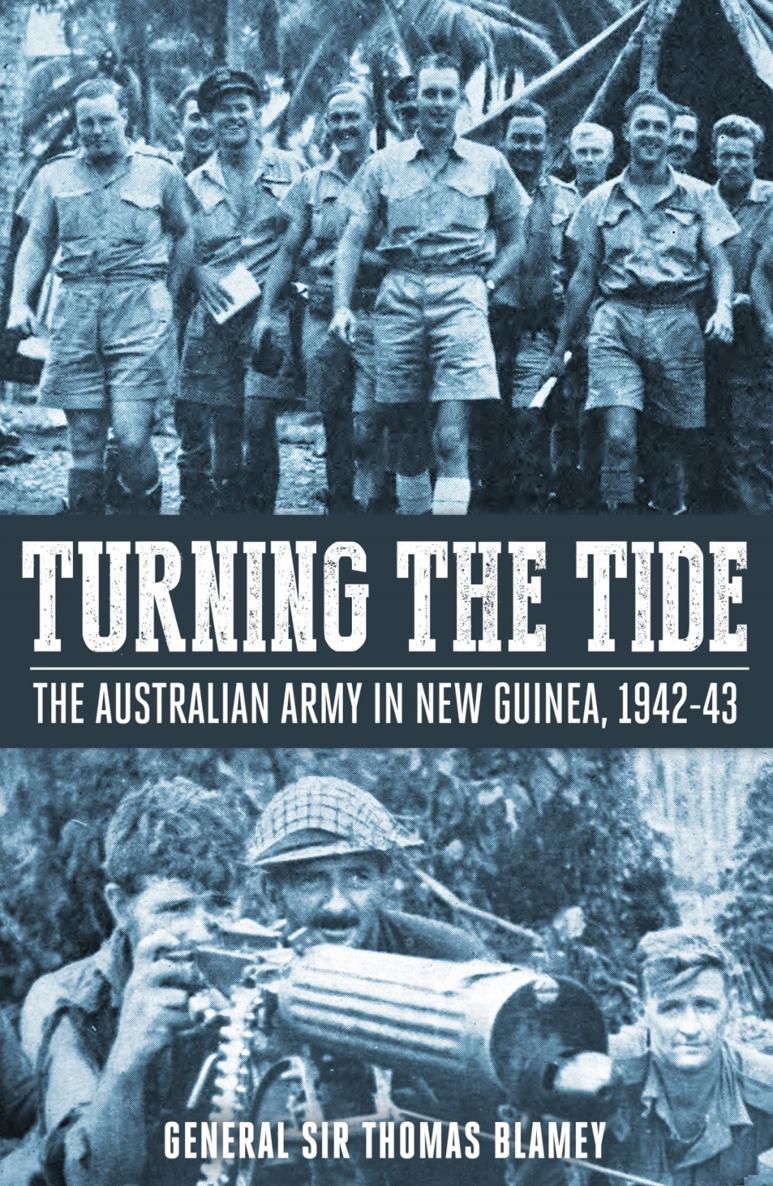

TURNING THE TIDE

The Australian Army in New Guinea, 1942-43

GENERAL THOMAS BLAMEY

Turning the Tide was originally published in 1944[?] as The Jap was Thrashed: An Official Story of the Australian Soldier, First Victor of the Invincible Jap by The Director General of Public Relations under the Authority of General Sir Thomas Blamey, Commander-in-Chief, Australian Military Forces

Foreword

Our army has never encountered anything more grim than the campaigns which have been fought in the jungles of New Guinea.

Australian troops had never previously been called upon to perform a harder task than that which faced us in New Guinea in the latter half of 1942. No Australian troops have acquitted themselves more honorably than those men who stopped the Japanese advance at Milne Bay and a little later in the Owen Stanley Ranges, and then began the process of throwing the enemy out of the territory which he had conquered.

The first A.T.F. never had a task more difficult than that which was fulfilled by the victors of the Owen Stanleys, and I say that as one who has an intimate knowledge of our soldiers in two world wars.

Some of the men who fought in these New Guinea campaigns had been through Greece and Crete; others fought in the North African desert; others in Syria; some were meeting an enemy for the first time. They proved their superiorityand that of the white racesover the beast from the Western Pacific, and they will go on proving it until victory brings peace again to the world.

General Thomas Blamey

Commander-in-Chief,

Australian Military Forces

Introduction

THE campaigns which were fought in New Guinea between August, 1942, and January, 1943, marked the turning of the tide in the Pacific war.

Until they metand ignominiously fled fromthe small Australian garrison at Milne Bay in August and early September, 1942, the Japanese had had an unbroken run of successful conquests.

The spurious legend of invincibility which they had built round themselves had acquired a superficial merit as they swept down through Malaya, the Netherlands Indies, Dutch and Portuguese Timor, New Britain, the Solomons and into New Guinea itself. Their planes had raided Darwin and other points of strategic importance on the Australian coast.

In New Guinea the Japanese, by the end of July, 1942, had substantial forces ashore at Lae, Salamaua, Finschhafen and Gona.

Between the enemy and the Australian mainland had stood less than four brigades of Australian troops. When the enemy initiated his two land drives aimed at the elimination of Port Moresby, there were two brigades at Milne Bay and two brigades were the garrison at Port Moresby. Small detached forces were operating in other parts of the island, their role being the harassing of the enemy and the gaining of information.

First Check

It was the two brigades at Milne Bay, supported by two squadrons of the Royal Australian Air Force, that stopped the Japanese Army for the first time in this war.

The two brigades at Port Moresby were reinforced substantially, chiefly by battle-tested Australians from the Middle East, before the enemys drive through the Owen Stanleys was stopped. American troops were employed later when the Japanese had been driven into his fox holes at Buna, Gona and Sanananda on the north coast of the island, where he was subsequently annihilated.

The rout of the Japanese invasion force at Milne Bay was completed in the first week of September, 1942. Within two weeks the enemys drive through the Owen Stanleys had carried him within 25 air miles of Port Moresby.

There, on Eoribaiwa Ridge, he was held after his final thrust in the direction of Port Moresby had been frustrated by an Australian ambush. He dug himself in on Eoribaiwa Ridge, but before the end of September he was on the run back through the mountains, leaving a trail of dead to mark his tracks.

So Eoribaiwa Ridge became a milestone in the Pacific War, for it marked the spot where the defensive was abandoned and Australian troops assumed the offensive as the spearhead of the United Nationsfor the first time since the attack on Pearl Harbor, more than nine months before, had brought war to the Pacific.

September 23, 1942, was the key date in the entire South-West Pacific campaign. Until that stage, due to innumerable factors, an offensive program to drive the enemy out of New Guinea had not been possible. The local command was preparing a local counter-offensive aimed at driving the Japanese back through the Owen Stanleys to Kokoda. But on September 23, General Sir Thomas Blarney, Commander-in-Chief of the Australian Military Forces, arrived in New Guinea to assume command, and immediately the counter-offensive was developed into a program aimed at the elimination of the enemy from Papua and by that means clearing the way for the eventual reconquest of the whole of New Guinea.

Within two days the counter-offensive was launched and the initiative has not since been surrendered by Australian and Allied troops.

The great merit of these initial Australian successes is that they were achieved against weight of numbers, by troops inexperienced in jungle warfare, and pitted against an enemy who had planned for years the conquest of the Pacific by the employment of his troops in just this particular type of warfare. The Australian troops, too, shared with all the United Nations, in the initial stages, the disability of inadequacy of equipment. They lacked also at this stage the essential command of the air.

A little later there was to be ample modern equipment and the 5 th United States Air Force and the Royal Australian Air Force were to dominate the skies, but in the early phases of the campaign the resources were small and seldom little more than the essential basic needs.

Among the dominating features in the preparation of this counter-offensive by the Australian troops was the almost complete absence of those base and supply facilities without which no Army can operate. New Guinea, for instance, was virtually a road-less country, and there was, in the early stages, insufficient aerial transport to provide the only practical alternative. The Australians held only two centers which could possibly have been developed as bases. At Milne Bay, with only one road and that often impassable because of mud, base facilities were virtually non-existent. Port Moresby was in a little better condition, but similar facilities were very deficient there also.