Contents

Guide

ALSO BY ANN McCUTCHAN

Wheres the Moon: A Memoir of the Space Coast and the Florida Dream

River Music: An Atchafalaya Story

Circular Breathing: Meditations from a Musical Life

The Muse That Sings: Composers Speak About the Creative Process

Marcel Moyse: Voice of the Flute

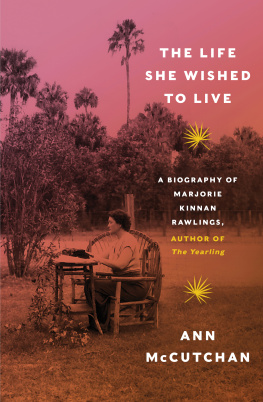

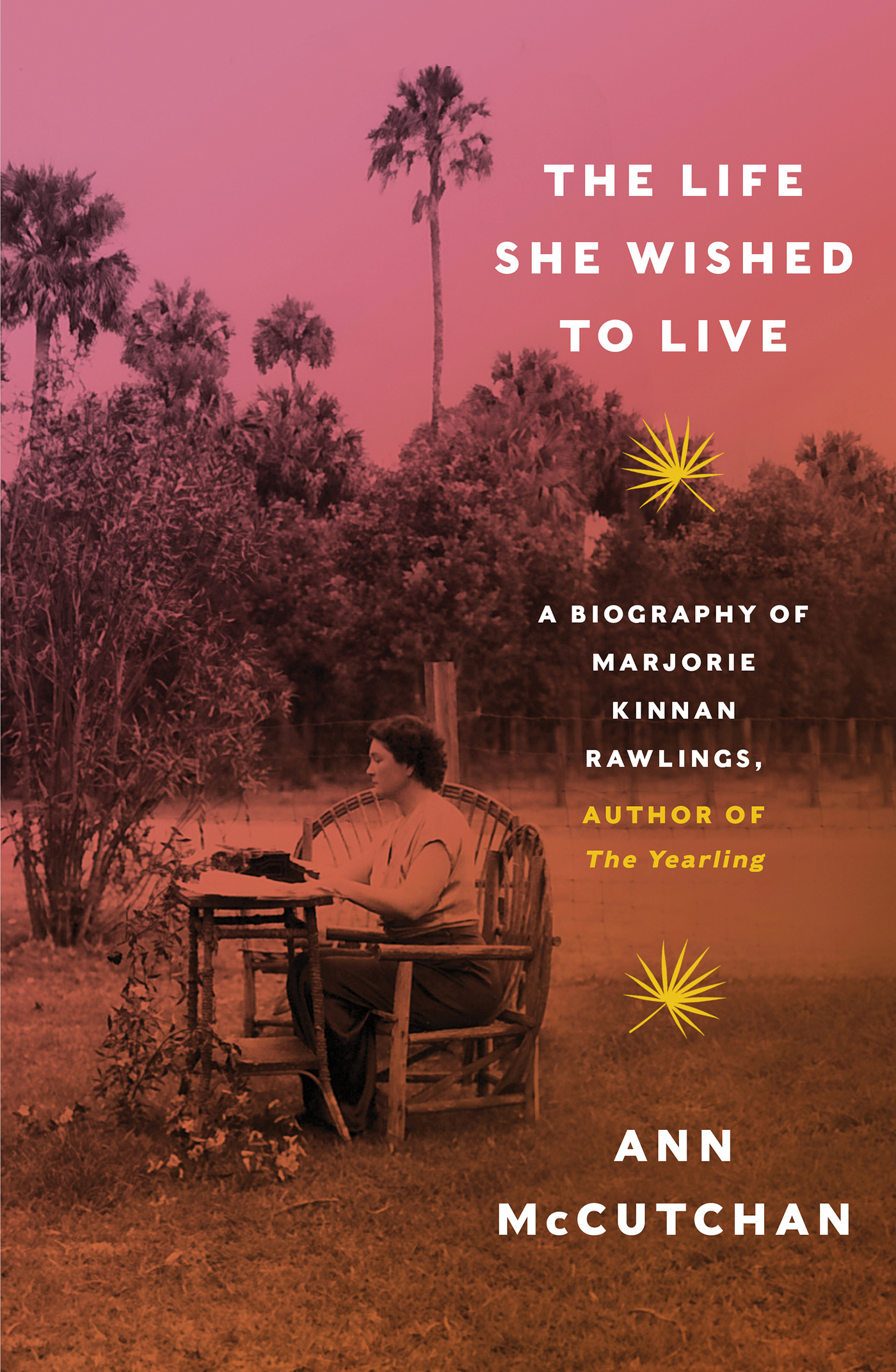

THE LIFE

SHE WISHED

TO LIVE

A Biography of

Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings,

Author of The Yearling

ANN McCUTCHAN

Copyright 2021 by Ann McCutchan

All rights reserved

First Edition

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to Permissions, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 500 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10110

For information about special discounts for bulk purchases, please contact W. W. Norton Special Sales at specialsales@wwnorton.com or 800-233-4830

Jacket design: Joanne ONeill

Jacket images: (photo of Rawlings) Marjorie Kinnan

Rawlings Collection, Department of Special and Area

Studies Collections, George A. Smathers Libraries,

University of Florida / Photo by Alan Anderson;

(palm leaves) Ketmut / Shutterstock

Production manager: Julia Druskin

The Library of Congress has cataloged the printed edition as follows:

Names: McCutchan, Ann, author.

Title: The life she wished to live : a biography of Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings, author of The yearling / Ann McCutchan.

Description: First edition. | New York, N.Y. : W.W. Norton & Company, [2021] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2020056028 | ISBN 9780393353495 (hardcover) | ISBN 9780393353501 (epub)

Subjects: LCSH: Rawlings, Marjorie Kinnan, 18961953. | Women authors, AmericanBiography.

Classification: LCC PS3535.A845 Z834 2021 | DDC 813/.52 [B]dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020056028

W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 500 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10110

www.wwnorton.com

W. W. Norton & Company Ltd., 15 Carlisle Street, London W1D 3BS

Dedicated to the memory of Joanne K. and Richard C. Bartlett

CONTENTS

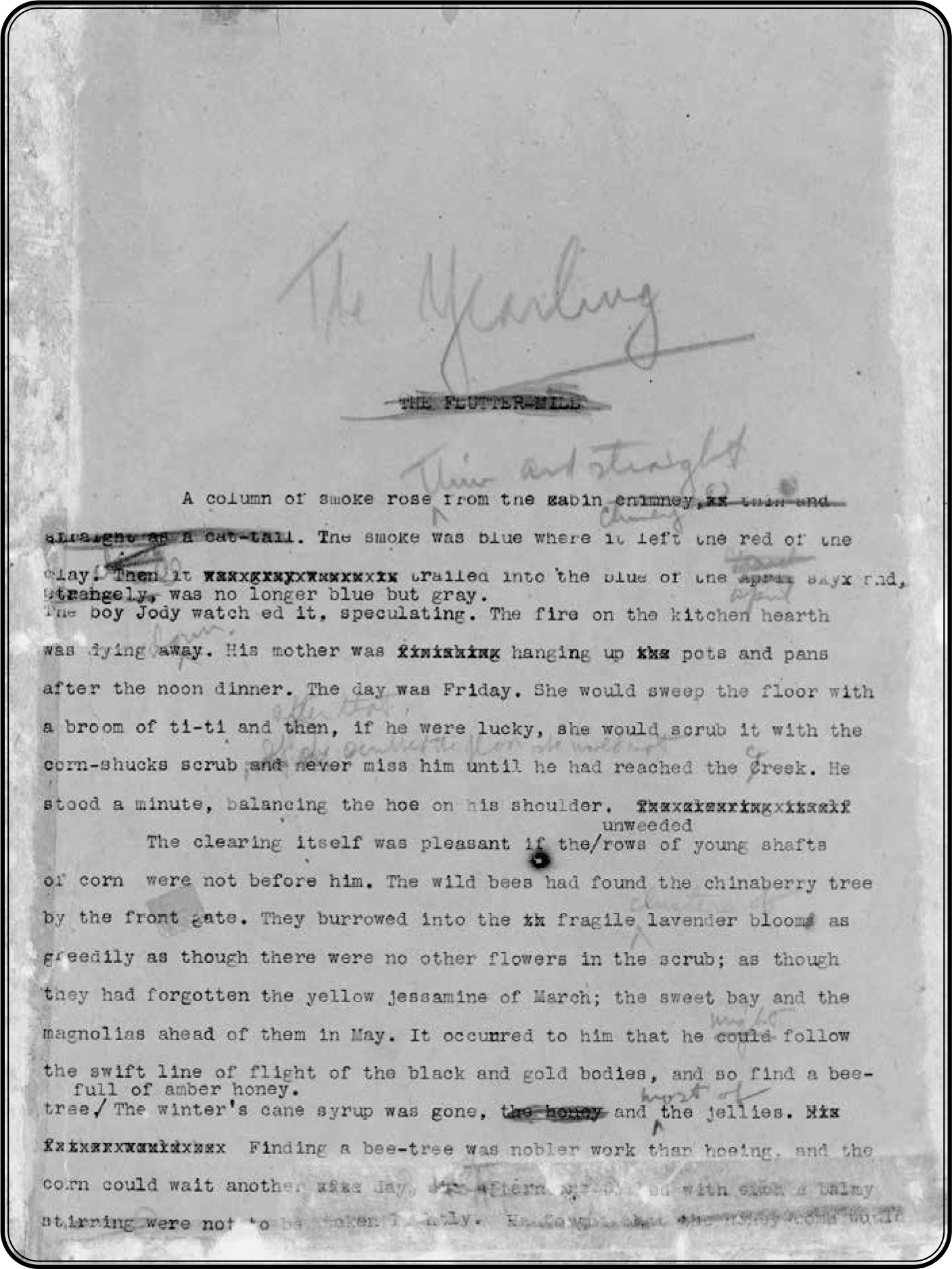

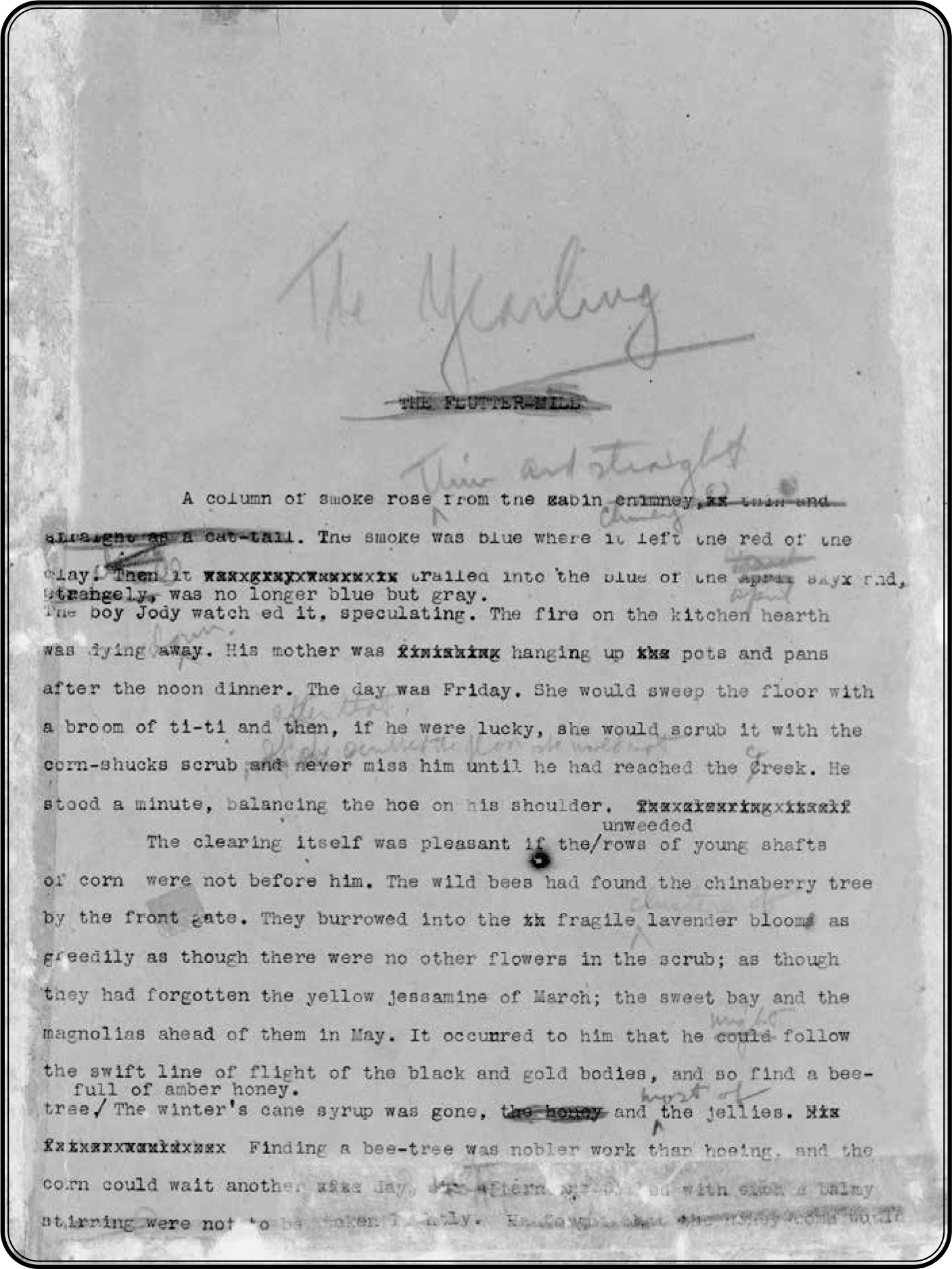

I first heard about Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings from my fourth-grade teacher at McNab Elementary in Pompano Beach, Florida. It was early spring, and Mrs. Chapman, a Florida native, decided it was a good time to share Rawlingss best-known novel, The Yearling , with twenty nine-year-olds. Every day after lunch, for weeks, she read aloud a few pages, inviting the class to listen for the authors beautiful sentences and the backwoods Florida world they brought to life. All of us, northern transplants whose families had been lured to the state by the postwar boom, were entranced by the story, delivered during that delicious drowsiness following milk and sandwiches by an old-timer whose voice was as soft and suggestive as distant radio waves. The Yearling was our first impression of Old Florida, the peoples speech and traditions, and Mrs. Chapmans reading seemed a private thing, a gift from her to us. We didnt know that the book, a coming-of-age story about a boy, his pet deer, and his parents, who farmed the north-central Florida scrub, had been the best-selling novel of 1938. Nor did we know the book had won the Pulitzer Prize and been translated into twenty-nine languages, or that Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer had made a popular film of it, starring Gregory Peck and Jane Wymanall before we were born. By the time Mrs. Chapman read it to us, The Yearling had come to be thought of as a childrens book, because it centered on a young boy. It was a staple of the elementary school story hour.

I loved The Yearling as one loves a fairy tale or a dream, and Mrs. Chapmans reading became one of my fondest memories. Much later, I read the novel by myself, silently, admiring it as magnificent storytelling, as literature. The novels lyricism, its fine rendering of country life, its use of local dialect, its structure and emotional range revealed Rawlings the artist, and I wanted to know how she, born in 1896, had become one. For clues, I took up her 1942 memoir Cross Creek , also a best seller in its day, and reveled in stories of the tiny Florida settlement where shed established her writing career in the 1930s. Cross Creek was the place out of which she wrote, no doubt a magical spot, and finally, I traveled to the area, which had changed very little since shed lived there. The hamlet was still a rural community on a stream between two lakes, Orange and Lochloosa, altered only by the soft conversion of Marjorie Rawlingss farmhouse, outbuildings, and orange grove into a state park with a paved road and guided walking tours. It was easy to imagine writing here. Still, I wondered, who was the artist whose life and work had made a shrine of this outpost? Where, beyond her two best-known books and Floridians sentimental tributes to her memory, was evidence of the complex woman Rawlings must have been?

In 2014, it seemed the only answer would be to pursue a biography of Rawlingsjust one existed, and it was more than twenty-five years old. When I contacted Florence Turcotte, the archivist for the Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings Papers at the University of Florida, I asked if there would be enough material to work with. No problemits one-stop shopping here, Flo said, and I quickly learned that the Rawlings archive is many -stops shopping, because the collection, including letters, manuscripts, news clippings, and photographs, is vastwhich I found both reassuring and intimidating. Even so, I suspected there were more resources to be discovered, and in time, that suspicion proved correct.

While I relied on every possible source to create Marjories portrait, two large bodies of work were critical. First, the more than four thousand letters to and from Marjorie and her many friends, lovers, family members, and professional associates offer an extraordinary look into the writers public, private, and interior lives. Her writings contain descriptions of experiences in New York City, Rochester, Cross Creek, and other locations; reactions to books, articles, and political developments; encounters with other writers; reports on her uneven health; armchair analyses of pals, acquaintances, and employees; and gossip. Letter writing in her lifetime was a standard form of extended, long-distance communication. Depending on where one lived, telephone use was to various degrees limited and expensive, and at Cross Creek, even when phones were finally available, the service was spotty and complicated by party lines.

Marjorie wrote many letters longhandand her hand was long: a bold, backhanded scrawl broken by extended dashes, as if she were speaking aloud, off the cuff. Possibly, she dashed off her boldest communiqus while drinkinga problem illuminated by her correspondence. Other letters were carefully composed and typed. Some read like set pieces worthy of a literary memoirist or a raconteuse, both of which she was. (Occasionally, some of these pieces or anecdotes appeared nearly word for word in letters to more than one person.) But whether set down by hand or type, Marjories letters are full-voiced, often performative. I might note here that quotations from the letters between Marjorie and Maxwell Perkins, her editor, and those from Marjorie to Norton Baskin, her second husband, reflect the punctuation decisions of Rodger L. Tarr, editor of Max and Marjorie: The Correspondence between Maxwell E. Perkins and Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings , and The Private Marjorie: The Love Letters of Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings and Norton S. Baskin. Punctuation decisions for quotations from other letters are mine.