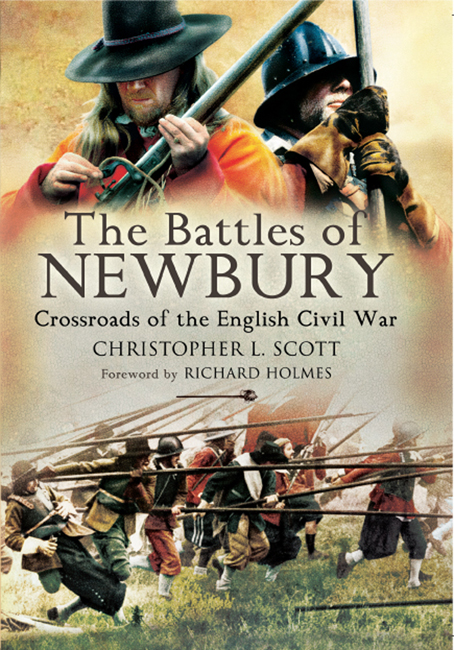

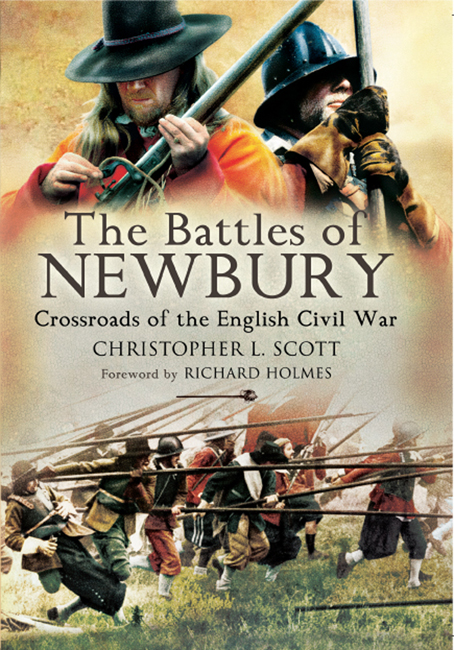

First published in Great Britain in 2008 by

Pen & Sword Military

an imprint of

Pen & Sword Books Ltd

47 Church Street

Barnsley

South Yorkshire

S70 2AS

Copyright Christopher L. Scott, 2008

ISBN 9781844156702

ePub ISBN: 9781844688524

PRC ISBN: 9781844688531

The right of Christopher L. Scott to be identified as the author of this work has

been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs

and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is

available from the British Library.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any

form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording

or by any information storage and retrieval system, without

permission from the Publisher in writing.

Typeset in Palatino by

Phoenix Typesetting, Auldgirth, Dumfriesshire

Printed and bound in England by

CPI UK

Pen & Sword Books Ltd incorporates the imprints of Pen & Sword Aviation, Pen &

Sword Maritime, Pen & Sword Military, Wharncliffe Local History,

Pen & Sword Select, Pen & Sword Military Classics and Leo Cooper.

For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact

PEN & SWORD BOOKS LIMITED

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

E-mail: enquiries@pen-and-sword.co.uk

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

Contents

List of Maps

General:

Newbury I:

Newbury II:

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

W ith any book there are many people to thank for help, and here I name those whom space will permit and ask those not named to forgive me.

Richard Ellis, battlefield photographer, battlefield walker and willing sounding-board for ideas and theories, for his enthusiasm and expertise in photographing the many scenes in this volume. I also thank him profusely for introducing me to Google Earth and the clues it can reveal.

Alan Turton, Curator of Basing House, long-time friend and an expert on the Earl of Essexs army, for advice and encouragement, as well as permission to freely make use of his research and the loan of many secondary and original sources.

Dr Eric Gruber von Arni, scholar and friend, for offering me unlimited access to his well-stocked military library and for teaching me the joy and skill of methodical research over the years.

Rupert Harding, of Pen & Sword, whose faith in my abilities was unshakeable and whose energy and range of interests are remarkable, and Sarah Cook, the editor, whose unseen skill has done much to improve my grammar.

Jason Clear and the Performing Arts staff of New College, Swindon, who let me downsize early, never moaned when I was out on battlefields rather than rehearsing plays and let me off directing the annual pantomime.

The staff of the libraries of Newbury, Swindon Borough, and New College, Swindon, and the ever-helpful volunteer staff of Newbury Museum, who must have thought my enquiries odd but managed not to show it.

Mr Colin Clark, whom I met by chance, who regaled me with local history, tales of the battle and landscape information, and the lady in Speen who showed me her cannonball!

Mr Steve Titcombe, another chance meeting, who told me of the discoveries in the fields of Newbury II, and all those other residents whose brains I picked and whose guidance on locations I sought, including the local historian who told me about lane name changes and the postman who was a mine of information despite not knowing anything about anywhere not on his round.

Professor Richard Holmes for agreeing to find time to both read my manuscript and write the foreword.

Iain Dickie and Nigel Pell of Miniature Wargames for their aid with the maps, as well as the Pen & Sword production team.

And finally Pamela Golding, my wife, who has listened to me talk about

Newbury, seen me disappear off to Newbury, and indeed has herself been shopping in Newbury more times than ever before, and has put up with a husband who seemed married to the PC!

This book is dedicated to Alan and Nicola Turton its a chantry thing.

And to his favourite general

the much-maligned and underrated Robert Devereux, 3rd Earl of Essex.

And you that know the gain at Newbury

Seeing the General, how undauntedly

He then encouraged you for Englands right

When royal forces fled, he stood the fight!

FOREWORD

I have a particular affection for the battlefields of Newbury. I well remember visiting them with justified trepidation, for they are not easy to interpret when I collaborated with Brigadier Peter Young on my first book, more than half a lifetime ago. Now I drive, almost every day, up and down the A34, that travellers friend but historians nightmare, that crosses them. The ruins of Donnington Castle catch the summer sun and stand out against the winter snow, and however often I see the sign to Wash Common it still stirs my spirits. Perhaps this is not the place to rail against the way that we treat battlefields, and because I am delighted to escape from the great Newbury traffic jam, part of me welcomes the new line of the A34. Part of me, however, regrets the way in which, driven by ignorance cloaked in necessity, we have buried still more of our past beneath concrete and tarmac.

I commend Chris Scotts book, surprisingly the first serious modern work on these two important battles, for two reasons. Firstly because, as an experienced re-enactor, he understands Civil War armies. The soldiers of the age were neither the elegant figures depicted in contemporary drill-books, nor the tens of extras, modern folk in ancient guise, that we so often see in television documentaries my own included. They were ground-crossing, load-bearing, horse-using creatures, who plied weapons which demanded strength and skill, and whose sense of drill and discipline often decided whether they won or lost. To understand seventeenth-century battles you must first understand seventeenth-century man, or his behaviour will at once interpose a barrier between past and present. It was still the stone age of command, with generals scarcely better served by communications than Julius Caesar had been. Maps were a rarity, and watches uncommon and poorly regulated, and most commanders relied in battle on the spoken message and shouted order. Even comparatively simple tasks, like the co-ordinated Parliamentarian attack which lay at the heart of Second Newbury, were easy to conceive but hard to execute. This is what Clausewitz was later to call friction the fact that in war everything is simple but the most simple thing is very difficult.

Second, there is no substitute for understanding microterrain, that tiny detail embedded firmly upon any landscape, even if it is apparently featureless. A fold in the ground here or a hillock there may easily make the difference between life and death, and features like sunken lanes and hedges (particularly the thick old stock-holding hedges that laced the fields of Newbury) were really important. Sturdy pikemen defending a hedgeline were a formidable obstacle, and even the best cavalry was sharply constrained if it had no room for manoeuvre.

There are some battlefields, like Naseby or Marston Moor, where terrain has changed comparatively little, though roads and enclosures have generally altered their details. But, as Chris Scott shows us so well, Newbury was a communication hub, given its strategic importance and the routes that ran through it. These and the railway and the canal that followed later, helped encourage development which makes interpreting these battles more difficult than usual. It is in relating the ground as it then was to the landscape that we now see that the author is so successful, and he brings the battlefield to life by showing us hedged lanes and hillsides that would have been familiar to the men who fought on them more than three and a half centuries ago.