2013 by Carl Sferrazza Anthony and the National First Ladies Library

All rights reserved

Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 2013012413

ISBN 978-1-60635-152-9

Manufactured in the United States of America

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Anthony, Carl Sferrazza.

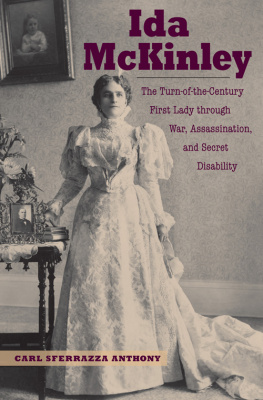

Ida McKinley : the turn-of-the-century first lady through war, assassination, and secret disability / Carl Sferrazza Anthony.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN 978-1-60635-152-9 (hardcover)

1. McKinley, Ida Saxton, 18471907. 2. Presidents spousesUnited StatesBiography.

I. Title.

E711.95.A57 2013

973.88092dc23

[B]

2013012413

17 16 15 14 13 5 4 3 2 1

To Martha whose fortitude helped me brace the rewriting of the lost Spanish-American War chapters, Pat whose resourcefulness rescued the lost pictures in the eleventh hour, and Mary whose faith in the value of this story never wavered.God gives us love. Something to love

He gives us; but when love is grown

To ripeness, that on which it throve

Falls off, and love is left alone.

Sleep sweetly, tender heart, in peace!

Sleep, holy spirit; blessed soul,

While the stars burn, the moon increase,

And the great ages onward roll.

Sleep till the end, true soul and sweet!

Nothing comes to thee new or strange.

Sleep full of rest from head to feet;

Lie still, dry dust, secure of change.

Alfred Lord Tennyson, To J. S.

(Ida Saxton McKinleys favorite poem)

Acknowledgments

FOR THEIR WORK in helping to produce Ida McKinley, I would like to thank Mary Regula, Martha Regula, and Pat Krider of the National First Ladies Library, independent researcher Craig Schermer, Janet Metzger formerly of the McKinley Presidential Museum, Nan Card of the Hayes Presidential Center, members of the board of the National Epilepsy Foundation who reveiwed text related to seizure disorder, Joyce Harrison, Christine Brooks, Susan Cash, Mary Young, and Will Underwood of the Kent State University Press, and copyeditor Valerie Ahwee.

The Red Room, 1899

IT WAS, SAID Miss Pauline Robinson of New York, like a mandate from Windsor, as if she were being presented to old Queen Victoria herself. A member of the wealthy, powerful, and socially elite DuPont family, at seventeen years old Pauline had already enjoyed privileges most Americans could not even imagine, yet she had never been so excited as when her closed coach drove in the White House gate. Along with another young debutante, a Miss Lee, and the wife and daughter of Washingtons Episcopal bishop, Pauline had been granted a private audience with the nations First Lady on Saturday, May 6, 1899.

Ascending the white marble North Portico steps and slipping into the old mansions entrance lobby, they were met in front of a garish wall of Tiffany glass by George Cortelyou, the presidents efficient secretary. Each handed this man with a mustache and monocle her engraved calling card. While he delivered their cards to the First Lady, they retreated to a dressing room to ensure that their appearance was meticulous, for even though the evening social call was designated en famille, it demanded strict adherence to a dress code. Miss Robinson wore a silk pink blouse, white skirt with tulle bow, a pink hat, and long white gloves. These times called for rigorous adherence to rituals of protocal, dictating matters like formal dress codes, intended to command respect for the ruling class of executive branch officials and ensure an equality of status among them with king, prime minister, or pasha. It was the dawn of the so-called American Empire.

Returning to retrieve the women, Cortelyou now escorted them down the gloomy, columned hall to the door of the Red Room. We were all announced in a loud tone of voice, Pauline reported in a letter to her mother two days later, and each then went up separately. As the women entered, two gentleman of the War Department immediately rose in attention and abruptly silenced whatever they had been discussing with the First Lady. Their presence, however, was not incidental to the drama that was unfolding in a private room right above them, which resulted in politics that would reverberate across the globe.

When my turn came, I put into practice the Dodworth curtsy, Pauline recounted, referring to a formal and proper manner of kneeling before royalty. It was quite effective and you know I did so because I saw at once Mrs. McKinley liked pomp and flattery. She was reclining in a chair, dressed in pale blue satin, her favorite color, and knitting slippers.

Reclining and knitting. Both activities were practically all the public had expected of Ida McKinley three years earlier during her husbands presidential campaign, the result of his crafting her persona, which both affirmed him as a martyr to her invalidism and prevented the truth about her nervous disability from being disclosed. Despite the greater understanding of neurological disorders at that time, a vast percentage of the general public would have ignorantly judged Mrs. McKinley to be better suited for an institution than the White House had they known she lived with epilepsy.

Keeping secret his own medicating of Ida and his perpetual search for a cure that did not exist, McKinley had little choice but to frame the reality of her unpredictable symptoms as a chivalrous matter of preserving the sanctity of her privacy. He cast her as so utterly dependent on his support, and the legend of his sacrifice so romantically played to the Victorian imagination, however, that not even newspaper articles reporting her activities that proved her strength and independence during the first half of her tenure as First Lady could counteract it.

From the moment she arrived in Washington, when she refused the use of a wheelchair and strode through the train station, Ida McKinley defied expectations. While acknowledging her chronically recurring immobility without shame, she sacrificed none of the traditional First Lady duties but rather adapted her condition to it, hosting weekly receptions, welcoming visiting delegations, attending state dinners, stopping to speak with tourists. Unable to tour welfare institutions, she delivered lavish bouquets from the presidential greenhouse and made hefty financial contributions. Her inability to headline fund-raising events was circumvented by donating personally knitted items for sale or auction. That evening in the Red Room, even Pauline Robinson was made to realize just how genuinely committed Ida McKinley was to this work. She told me with evident pride that she had made 4,000 pairs, the young woman wrote, and one pair brought 300 dollars for a fair last year.

In deeds both large and small, Ida McKinley impressed her personality on the public, whether it was ignoring pressure from the temperance movement and deciding to serve alcohol to guests or refusing to attend church on Sunday with her husband to instead indulge her passion for theatrical comedies with friends. Not only did she travel extensively with the president around the nation, she left him in Washington to make excursions on her own. In fact, Ida McKinley would become the first incumbent First Lady to break custom and briefly travel to another country.