Bibliographical Note

This Dover edition, first published in 2013, is an unabridged republication of the work originally published by Henry Regnery Company, Chicago, in 1961.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

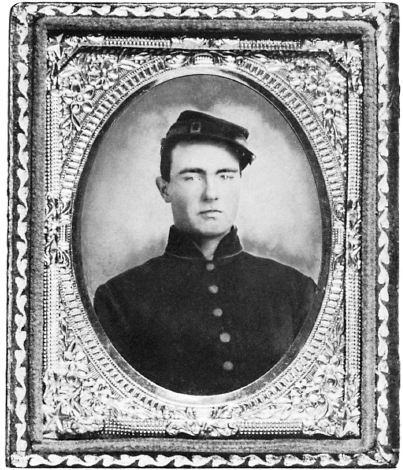

Strong, Robert Hale, 1842-1928.

A Yankee privates Civil War / Robert Hale Strong ; edited by Ashley Halsey. Dover edition.

p. cm.

Originally published: 1961.

ISBN-13: 978-0-486-49713-6

ISBN-10: 0-486-49713-5

1. Strong, Robert Hale, 1842-1928. 2. United States. Army. Illinois Infantry Regiment, 105th (1862-1865) 3. United StatesHistory Civil War, 1861-1865Personal narratives. 4. IllinoisHistoryCivil War, 1861-1865Personal narratives. 5. United StatesHistory Civil War, 1861-1865Campaigns. I. Halsey, Ashley, editor. II. Title.

E505.5105th .S77 2013

973.7'8dc23

2012041700

Manufactured in the United States by Courier Corporation

49713501 2013

www.doverpublications.com

Foreword

THIS is the story of a war fought by the youthful soldiers of a young nation. There was never another war like it in America, and we can hope and pray that there never will be again.

Most of the 2,500,000 Federal and 1,000,000 Confederate soldiers were not old enough to vote, but one in seven was old enough to die like a man. There were few beat youngsters among them even in the regiments which the Union raised from ex-slaves. Northerner and southerner alike usually needed no urging to go into battle. In combat, they fired with cold-eyed accuracy. Unlike some 20th century American infantry who could not or would not shoot at all, the boys in blue and gray shot to kill. They had no modern inhibitions; the word itself had not been invented. War meant kill or be killed. So they ran up the highest death rate in any of our conflicts.

One reason for the unstinted ferocity on both sides was that these millions were mostly youths proving themselves in a day when proof was required. They stood at the threshold of manhood and too many paid for admission with their lives. Cowardice was never more unstylish, nor casual bravery more current. Time and again, groups of enlisted men sought out the enemy and waged their own little battles without an officer present at all.

A distinctive thing about this book is that it is told entirely from the viewpoint of a private. Robert Hale Strong, who relates this tale, was a 19 year-old farm boy in northern Illinois when his father decided he could be spared from the crops to go to war with the 105th Illinois Volunteer Infantry. Strong made an exceptional private. He took to war with him not only a shrewd American humor which smacks at times of Mark Twains but an instinctive skill in reporting what he saw. And because he was always volunteering to forage or picket, he saw far more than the average soldier tramping along in dusty ranks.

As an associate editor handling The Saturday Evening Posts war centennial series, I read hundreds of unpublished manuscripts. Of them all this gave the best and clearest insight into how the war really looked to a foot-slogging infantryman whom circumstances at times reduced to the level of a wild beast but who never forgot home, mother, decency and humanity.

Strong in his account reduces the role of citizen-soldier to hardshouldered realism. He refers consistently to combat of the bloodiest sort as work. It was our workcharging into the muzzles of an enemy battery. It was pretty hard workfighting through mud and across enemy entrenchments. It was work we knew was cut out for us. And the work was not eight or twelve hours, but twenty-four hours.

Strong returned home unwounded at the close of the war, but never recovered from the rheumatism contracted while sleeping in the rain. Bouts of it racked him so badly that he moved from Illinois to Arkansas in search of a warmer climate. During one long siege of rheumatism, he began writing in response to a promise to his mother to tell his war experiences. She produced packets of his letters and wartime diaries which she had carefully saved. Refreshing his memory from these, he wrote his story in fits and snatches, at times stopping when he did not feel well enough to hold a pen. His mother transcribed his notes in longhand into composition books.

Strongs daughter, Mrs. J. M. Bill, of Ozark, Arkansas, preserved the original manuscript. Her daughter, Mrs. Jeanne Ross, of Warren, Arkansas, typed it up. In its original form, it ran 130 manuscript pages without a paragraph but the words flowed just as Strong had spoken them nearly a hundred years ago.

ASHLEY HALSEY, JR.

A Yankee Privates

Civil War

A Regular Soldiers Song

Hunger and thirst, hunger and thirst;

Give my my pipe, let em do their worst.

Cold and wet, cold and wet;

Give me my pipe, I soon can forget.

Sickness and pain, sickness and pain;

Give me my pipe, and I wont complain.

Powder and ball, powder and ball;

Give me my pipe, Ill smoke till I fall.

Battle and blood, battle and blood;

Give me my pipe, itll still taste good.

Wounds and death, wounds and death;

Ill draw on my pipe with my dying breath.

Prologue

WELL, MOTHER, I did not think, when I told you last night that I would begin my recollections of the war when I was too lame to work, that the time would come so soon. But here I am, laid up for a while. So I shall start talking and you start writing. Will you want all I can remember? If I had a gift at story telling, I might maybe make it interesting.

Lets see, to begin...

I remember the excitement when news first came that the South had seceded. Indignation was felt by all except Copperheads and dough-faced Democrats. I remember the public meetings in the churches and farmhouses: how G.F. and his father blew the fife and beat the drum and exhorted the men to rally round the flag. I remember, too, how G.F. and his father did not do any rallying themselves, but stayed at home and raised wheat and corn and pork for a big price, for the government to buy for the boys who did rally.

I remember how Father told me, when I asked him to let me enlist, that he would let me go when he thought I was needed; and how I thought the war would be over before I would get a chance to win any glory. How large I felt when Father said to me one day, If you still wish to enlist, now is the time for you to go.

I walked straightway to Naperville and wrote my name as big as any manI was going on nineteenon the page among the other heroes. I remember how long a time it seemed to me before we were finally ordered to rendezvous at Dixon, and how you and Father took me to Wheaton where I, in company with my future comrades, was to take the train to Dixon to go into camp for instruction and drill. The first night in Dixon, we found that no barracks had been prepared for us and we had as yet drawn no blankets. So we had to go to hotels and pay our own bills. We were ready, but the army was not ready for us.