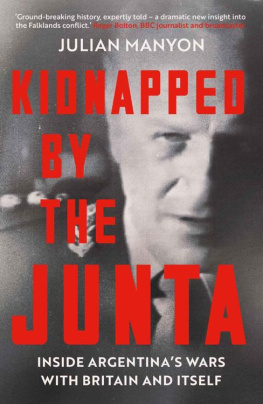

Julian Manyon - Kidnapped by the Junta

Here you can read online Julian Manyon - Kidnapped by the Junta full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2022, publisher: Icon Books, genre: Non-fiction. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Kidnapped by the Junta

- Author:

- Publisher:Icon Books

- Genre:

- Year:2022

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Kidnapped by the Junta: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Kidnapped by the Junta" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Kidnapped by the Junta — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Kidnapped by the Junta" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Contents To my son Richard for his steady encouragement throughout and to my dear wife Caroline without whose help this book could not have been completed. Julian Manyon was a journalist specialising in international stories for more than 40 years, starting in Vietnam. He covered the Falklands War in Argentina for Thames Televisions TV Eye and then became a long-serving foreign correspondent for ITN, winning numerous awards for his work. He lives with his wife on their small farm in the south of England.

Contents To my son Richard for his steady encouragement throughout and to my dear wife Caroline without whose help this book could not have been completed. Julian Manyon was a journalist specialising in international stories for more than 40 years, starting in Vietnam. He covered the Falklands War in Argentina for Thames Televisions TV Eye and then became a long-serving foreign correspondent for ITN, winning numerous awards for his work. He lives with his wife on their small farm in the south of England. A MID ALL THE DRAMAS of the career in journalism that I had so much desired, I had not expected to have an hour to contemplate my own imminent execution.As the car rolled forward at a deliberately steady pace, I lay constrained and helpless on my back in the rear footwell, a cloth over my head blocking almost all vision, a mans knee jammed against my neck pinning my head against the back of the seat in front and a hard, tanned hand holding an automatic pistol pressed against the side of my head.The words were in Spanish but even with my fragmentary knowledge of the language I could understand them. Quiet, the harsh voice said, and then with a short gesture of the pistol, When we get where we are going, I will kill you with this.It was May 12th, 1982, in the age before training courses in hazardous environments and psychological counselling. As I briefly reflected on the mess in which I found myself, only unhelpful thoughts occurred.I had been close to death before. So determined had I been to become an international journalist that more than a decade earlier I This was different but, if anything, even more terrifying: a slow steady progress through moving traffic in the streets of Buenos Aires as I lay helpless and unable to affect my fate in any way. In the jargon of the Argentinian secret police which I learned later, I had been swallowed and walled in.There were three men in the saloon car that carried me: the driver, a man in the front seat operating a radio on the dashboard and the man holding the gun to my head who appeared to be their commander. Brief incomprehensible radio messages were occasionally exchanged.One thing was very clear: the men who had seized me and who now held my life in their hands were professionals in the art of kidnapping. In the early afternoon, together with the other members of our British television team, I had emerged from the Argentine Foreign Ministry after a failed attempt to interview Minister Nicanor Costa Mndez, the Oxford-educated civilian described by some as the evil genius of the military regime. Costa Mndez, who walked with the aid of a stick, had been angered by the press of journalists and my insistent questions and brushed us off with an infuriated wave of the hand. Minutes later, as we stepped into the tree-lined square outside the handsome colonial-style building and got into our car, I was suddenly swept up in a series of events that seemed to happen in slow motion but in reality occurred at lightning speed: another car, which I remember as being grey in colour, cut in front of us forcing us to stop and disgorged strongly-built men clad in sharp suits. They seized me with firm hands while shouting, Police! Suddenly I was looking up at trees we had been passing and, before I could make any real attempt at resistance, I was propelled into the back of their vehicle. A pistol was pressed against my head. I had no idea what was happening to the rest of the team. I just knew that they werent there.The doors slammed shut and in a motion that immediately terrified me, the men produced what appeared to be custom-made leather thongs with which they expertly tied the door handles to the door locks in this pre-electronic vehicle. As I dimly realised amid the shock and mounting panic, this made it virtually impossible for me or any other victim, no matter how desperate, to kick open a door. It was a practised routine which these men had clearly carried out many times before.The car, built by the Ford factory in Argentina, was called a Falcon, a solid, practical model that was already notorious as the vehicle of choice of the secret police. It moved quietly through the streets which despite the war with Britain were choked with traffic. As was their aim, the kidnappers had achieved complete control. Resistance was beyond my power and would, in any case, have been futile and probably fatal. From beneath the cloth covering my head I caught occasional glimpses of the upper storeys of some of the buildings we were passing, the fine old ones in the centre, then more modern structures as we began to move towards the outskirts of the city.Suddenly I saw gantries carrying familiar yellow signs advertising the Lufthansa airline and realised that we were passing the international airport where we had arrived some ten days before.Look, I said in broken Spanish-English to the man holding the gun to my head, In my pocket Ive got dollars. Please take the money and throw me out here.No word came in reply but I felt a horny hand force its way into my trouser pocket searching for the money, some $800, which he silently removed. Without the slightest change of pace, the car rolled on. When I made another attempt to speak I was silenced with a slap. Then, as our car seemed to move through traffic, my knees were struck with the pistol butt to make me pull them down beneath the level of the window.But as my kidnapper scrabbled for the money he had given me a brief glimpse of his face. I was too frightened to look at him calmly with a view to recall but something remained lodged in my memory all the same. Notes The destruction of the Cambodian Army battalion I was accompanying took place on November 23rd, 1970 near the town of Skoun, north of the Cambodian capital Phnom Penh. United Press International reported on the battle and my escape on November 24th.

A MID ALL THE DRAMAS of the career in journalism that I had so much desired, I had not expected to have an hour to contemplate my own imminent execution.As the car rolled forward at a deliberately steady pace, I lay constrained and helpless on my back in the rear footwell, a cloth over my head blocking almost all vision, a mans knee jammed against my neck pinning my head against the back of the seat in front and a hard, tanned hand holding an automatic pistol pressed against the side of my head.The words were in Spanish but even with my fragmentary knowledge of the language I could understand them. Quiet, the harsh voice said, and then with a short gesture of the pistol, When we get where we are going, I will kill you with this.It was May 12th, 1982, in the age before training courses in hazardous environments and psychological counselling. As I briefly reflected on the mess in which I found myself, only unhelpful thoughts occurred.I had been close to death before. So determined had I been to become an international journalist that more than a decade earlier I This was different but, if anything, even more terrifying: a slow steady progress through moving traffic in the streets of Buenos Aires as I lay helpless and unable to affect my fate in any way. In the jargon of the Argentinian secret police which I learned later, I had been swallowed and walled in.There were three men in the saloon car that carried me: the driver, a man in the front seat operating a radio on the dashboard and the man holding the gun to my head who appeared to be their commander. Brief incomprehensible radio messages were occasionally exchanged.One thing was very clear: the men who had seized me and who now held my life in their hands were professionals in the art of kidnapping. In the early afternoon, together with the other members of our British television team, I had emerged from the Argentine Foreign Ministry after a failed attempt to interview Minister Nicanor Costa Mndez, the Oxford-educated civilian described by some as the evil genius of the military regime. Costa Mndez, who walked with the aid of a stick, had been angered by the press of journalists and my insistent questions and brushed us off with an infuriated wave of the hand. Minutes later, as we stepped into the tree-lined square outside the handsome colonial-style building and got into our car, I was suddenly swept up in a series of events that seemed to happen in slow motion but in reality occurred at lightning speed: another car, which I remember as being grey in colour, cut in front of us forcing us to stop and disgorged strongly-built men clad in sharp suits. They seized me with firm hands while shouting, Police! Suddenly I was looking up at trees we had been passing and, before I could make any real attempt at resistance, I was propelled into the back of their vehicle. A pistol was pressed against my head. I had no idea what was happening to the rest of the team. I just knew that they werent there.The doors slammed shut and in a motion that immediately terrified me, the men produced what appeared to be custom-made leather thongs with which they expertly tied the door handles to the door locks in this pre-electronic vehicle. As I dimly realised amid the shock and mounting panic, this made it virtually impossible for me or any other victim, no matter how desperate, to kick open a door. It was a practised routine which these men had clearly carried out many times before.The car, built by the Ford factory in Argentina, was called a Falcon, a solid, practical model that was already notorious as the vehicle of choice of the secret police. It moved quietly through the streets which despite the war with Britain were choked with traffic. As was their aim, the kidnappers had achieved complete control. Resistance was beyond my power and would, in any case, have been futile and probably fatal. From beneath the cloth covering my head I caught occasional glimpses of the upper storeys of some of the buildings we were passing, the fine old ones in the centre, then more modern structures as we began to move towards the outskirts of the city.Suddenly I saw gantries carrying familiar yellow signs advertising the Lufthansa airline and realised that we were passing the international airport where we had arrived some ten days before.Look, I said in broken Spanish-English to the man holding the gun to my head, In my pocket Ive got dollars. Please take the money and throw me out here.No word came in reply but I felt a horny hand force its way into my trouser pocket searching for the money, some $800, which he silently removed. Without the slightest change of pace, the car rolled on. When I made another attempt to speak I was silenced with a slap. Then, as our car seemed to move through traffic, my knees were struck with the pistol butt to make me pull them down beneath the level of the window.But as my kidnapper scrabbled for the money he had given me a brief glimpse of his face. I was too frightened to look at him calmly with a view to recall but something remained lodged in my memory all the same. Notes The destruction of the Cambodian Army battalion I was accompanying took place on November 23rd, 1970 near the town of Skoun, north of the Cambodian capital Phnom Penh. United Press International reported on the battle and my escape on November 24th.  I N M AY 1982 the eyes of the world were fixed on events taking place at one of the most remote and obscure points on the planet. So little-known were the Falkland Islands that some of the British servicemen hastily dispatched there had initially believed that they were being sent to islands north of Scotland rather than to the middle of the South Atlantic. Even the then Defence Secretary, Sir John Nott and the Chief of the General Staff, Lord Bramall, later confessed to similar ignorance when they both told a seminar in June 2002 that at the outset they had had no clear idea of exactly where the islands lay.In my case, though claiming no greater knowledge, I was at least in the right continent when the crisis erupted in late March. Together with a crew from Thames Televisions current affairs programme TV Eye I was filming a report on the elections in war-torn El Salvador, the second time I had been sent to that beautiful, unfortunate land on the north-west coast of Latin America. Our team included cameraman Ted Adcock, a dashing figure and winner of awards for his work, soundman Trefor Hunter, quiet, reserved and highly professional, and our producer, Norman Fenton, a canny, bearded, Scots-accented veteran of the television industry. Together we filmed blown bridges and murder victims lying in the street and took cover as an election office came under fire. Then came a telephone call from our Editor in London.Mike Townson was a man possessed of a curious charisma with his stocky, overweight frame and heavy lips. He had always reminded me of a tribal chieftain making his dispositions from the substantial chair behind his desk. Now his instructions were brisk and to the point. Some Argentines had landed on a British-owned island called South Georgia. It was becoming an international crisis. We should leave El Salvador immediately and head for Buenos Aires. Try to keep out of trouble, he said helpfully.We had no idea how British journalists would be received in Argentina and it was agreed that our team would split up and make our way there by different air routes, in my case via Miami and Santiago in Chile. In fact, even though our journey took place just as Argentine troops were landing on the Falkland Islands, we experienced no difficulty with passport control or customs in Buenos Aires and were soon reunited. Following journalistic instinct, we quickly boarded yet another aircraft and flew to Comodoro Rivadavia, a southern oil town in Argentinas tapering cone that ends near Antarctica and one of the key locations from which the invasion of the Falklands was being staged. There we had our first brush with the reality of trying to cover events in a country with which Britain was now effectively at war.Within a few minutes of our arrival in the somewhat barren settlement, we were arrested by secret policemen dressed in plain clothes and equipped with pistols and walkie-talkies. They told us that Comodoro Rivadavia was now a military zone and escorted us to a local hotel where, as soon as we checked in, all the telephones were cut off to prevent us making outside calls. We were then told that we must leave the area by 10am the following day. Early next morning, in our desire to get at least a few images from the trip, we attempted to film a view of the ocean, looking in what we imagined was the direction of the Falkland Islands, and were immediately arrested by armed soldiers. Fortunately they were appeased by our promise to leave the town and we were permitted to return to the local airport, where we saw exactly why security was on such high alert. The runway was now lined with troops with their packs and rifles waiting to board C-130 transport aircraft for their flight to the Falklands. It was visual evidence that the Argentine Junta had no intention of backing down and was instead doubling up on its bet of seizing the islands.We were able to fly back to Buenos Aires and in retrospect had been extremely fortunate. A few days later, three other British journalists, Simon Winchester of The Sunday Times and Ian Mather and Tony Prime of The Observer , ventured even further south and were also arrested. However, they were charged with espionage and spent the next twelve weeks as the war was fought sharing a cell in an unattractive Argentine prison which also housed thieves and murderers. It has occurred to me to wonder whether the relative ease of our own return to the capital produced in my case a certain over-confidence that contributed to our later near-disaster.With the clarity of hindsight we were dangerously naive. Reporting on a war from the enemys capital held obvious perils, but even as the British task force assembled and set out we were among those prey to the widespread belief that this confrontation would end without serious bloodshed. Our first days in Buenos Aires only served to strengthen the sense of unreality.Even as the crisis gathered pace the Argentine capital remained a captivating city which symbolised the countrys extraordinary history: the elegant centre with its fine French-style neo-classical buildings, punctuated by florid Art Nouveau masterpieces, all products of the astonishing building boom between 1880 and 1920 when Buenos Aires was one of the fastest-growing cities in the world and Argentina, fuelled by its vast agricultural hinterland, seemed destined to become one of the worlds richest countries.It was a land originally seized by Spanish soldiers and fortune-hunters who had exterminated or driven out most of its indigenous Amerindians now just 2% of the population and was then filled by waves of European immigrants ranging from Italian slum-dwellers to English landowners, Russians trying to escape Tsarism or revolution and yet more Spaniards, often peasants from Galicia or the Basque country. There were also Japanese hungry for opportunity who set up their own Spanish-speaking tribe. In similar fashion to the United States, this was a country built by tough-minded incomers and indeed the sheer volume of immigration was second only to the US. The resulting architectural styles of Buenos Aires reflect the utopian ambitions of the designers as well as their foreign heritage, and speak more to aspiration than to a reality in which boom was regularly followed by crushing economic bust. On Avenida Rivadavia, named after the first President of Argentina, we saw the two splendid Gaud-influenced masterpieces: the Palace of the Lilies and the other fine building next door, which bears on its faade a legend reading, There are no impossible dreams. But in the outlying areas beyond the centre, the miles of often crudely built housing and commercial blocks testified to the struggles and disappointments of what was painfully becoming a Latin American megapolis.In May 1982, as the British task force sailed towards the Falklands or as Argentines call them Las Malvinas, using the name given to them by French explorers who were in fact the first to settle the islands many in Buenos Aires found themselves dreaming of national fulfilment. Raising the Argentine flag over those windswept outcrops would finally transcend dictatorship, terrorism and the never-ending economic crisis in which inflation had reached 150% and the peso was almost valueless. There was intoxicating drama in the rallies in front of the Presidential Palace, the Casa Rosada or Pink House, known in the Anglophone community as the Pink Palace, where General Leopoldo Galtieri, leader of the military Junta who had ordered the seizure of the islands after only four months in power, appeared on a balcony in the style of Argentinas earlier celebrated leader Juan Pern and delivered a nationalist clarion call to a vast, excited crowd. In the streets were columns of cars with drivers flying the Argentine flag and sounding their horns, and all over the city an excited buzz fed off the newspaper headlines announcing Argentinas preparations for air and naval war and the certainty of their victory. I was welcomed to the offices of the leading newspaper Clarn by its Foreign Editor Roberto Guareschi, as the papers journalists pounded the metal typewriters of that era to produce yet more optimistic copy. In remarks that were typical of the coun-trys mood but seem tragically out of touch in the light of events, Guareschi told me that Margaret Thatcher and the British government appeared confused: They dont know whether to use force or not. First they say they might use it. Then they say they wouldnt use it. I guess that all this is only to be tough before negotiationsLike many Argentines Mr Guareschi had convinced himself that Mrs Thatcher would negotiate a settlement: I dont give much importance to the public British proposals, he told me. I guess that in the end at the negotiation table the proposals will be more realistic.Argentines with an interest in history like our excellent interpreter/researcher Eduardo harked back to another war in the early Now hailed in Argentina as a landmark victory, the war with Britain opened the way for the country to declare independence from Spain nine years later in 1816.In 1833 Britain successfully asserted her naval power by seizing full control of the Falkland Islands, where the British had first landed more than 100 years earlier, and removing some of the small number of Argentinians who had settled there. For the now-powerful British Empire this was little more than a geopolitical footnote that scarcely registered in the publics consciousness, but for the new nation of Argentina it became a running sore. Economic relations between Britain and Argentina grew and prospered, with Britain for many years effectively controlling the Argentine economy, but Argentines continued to hark back to their first triumphs over the redcoats. The bodies of several hundred British soldiers, mostly Scottish Highlanders, are said to be buried under Avenida Belgrano in central Buenos Aires and the colours of the British 71st Regiment of Foot, together with two Royal Navy banners, are still held at the Santo Domingo convent. In 1982 the lesson that many Argentines drew from this was that victory over Margaret Thatchers task force, however well-equipped and heavily armed, was possible.Lucia Galtieri, the wife of the dictator, attended prayers at a church which was a bastion of resistance to the British Army in 1806. Afterwards she told us of the emotional attachment Argentinians felt for the islands: The Malvinas are not just a myth. They are a longing, a desire Everybody in Argentina agrees that the Malvinas should again become part of our national patrimony.Las Malvinas son argentinas were the words on every lip and, a little surprisingly, they were often accompanied by smiles of welcome when we identified ourselves as British journalists seeking to report their views of the war.Above all the city itself still had the energy for which Buenos Aires was famous. This, as any Argentine would tell you, was the country that had produced Formula Ones greatest racing driver in Juan Manuel Fangio, five times world champion in the tourna-ments first decade, as well as footballers who had won the World Cup and dazzled soccer fans everywhere, a country which each year on December 11th celebrates a national day of Tango. At the end of April 1982, cafes were packed and restaurants full of people feasting on the countrys legendarily massive and surprisingly tender steaks washed down by flagons of hearty red wine, an elixir which for many bred ebullient optimism. The military men we were able to interview were more restrained in their assessments but absolutely uncompromising in the message they wished to convey. Admiral Jorge Fraga, a cheerful balding expert in sea warfare from the Argentine Naval College, claimed to be heartened by the relatively small size of the British task force, which included fewer than 5,000 combat troops in defiance of the traditional military formula, which would give the Argentine soldiers now entrenched in the Falklands a key strategic advantage. His thinking clearly reflected the beliefs of the military Junta which he served: You know that invasion needs seven soldiers attacking for each one defending, so I think that to have success the British will need about 40,000 soldiers. If not they will lose men and ships and maybe suffer disaster.I then asked him a question which seemed obvious even before the events that followed. Could the result in fact be a disaster for the Argentine Navy? I received a chilling reply: Maybe our Navy too, he said, but our objective is to stay in the islands and we are going to stay.Prayers and rhetoric were soon to be replaced by the frightening drumbeat of war. On May 1st a giant RAF Vulcan bomber, flying at extreme long range from Ascension Island with the help of repeated air-to-air refuelling, struck Port Stanley airfield and cratered the runway with one of its 1,000lb bombs. This was followed by another raid on the airfield by Royal Navy Sea Harriers. Hours later, Argentinian Air Force jets attacked the Royal Navy task force, causing limited damage to two British ships. Twenty-four hours after that, the Royal Navy struck in clinical and devastating fashion. The antiquated Argentine cruiser General Belgrano was torpedoed and sent to the bottom by the British nuclear submarine HMS Conqueror with the loss of 323 lives.Britains sinking of the Belgrano has been hotly debated, a debate which continues to this day. Was the out-of-date warship which as the USS Phoenix had survived the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor and then served in the Pacific theatre throughout the Second World I do not intend to contribute to this argument, which reached a bitter climax when Mrs Thatchers husband Denis accused BBC producers of being Trots and wooftahs after they broadcast a celebrated television confrontation between the Prime Minister and a critical and well-informed member of the public a year after the sinking. What I can personally testify to is the surge of shock and grief which ran through Buenos Aires when reports of the sinking were confirmed after being initially denounced as lies by the Junta. At our hotel young women, who normally worked there cheerfully, appeared close to tears. It took almost 48 hours for what had happened to become clear, hours in which men struggled and drowned or froze to death in the chill waters of the South Atlantic, hours in which a terrible pall of sorrow and growing apprehension hung over the city. On May 4th the Argentine government issued a statement on the sinking: At 17 hours on 2 May, the cruiser ARA General Belgrano was attacked and sunk by a British submarine in a point at 55 24 south latitude and 61 32 west longitude. There are 1,042 men aboard the ship. Rescue operations for survivors are being carried out That such an attack is a treacherous act of armed aggression perpetrated by the British government in violation of the UN Charter and the ceasefire ordered by United Nations Security Council Resolution 502 That in the face of this new attack, Argentina reiterates to the national and global public its adherence to the ceasefire mandated by the Security Council in the mentioned resolution. In fact diplomacy was already failing with the unsuccessful visit and brusque departure of the US Secretary of State Alexander Haig and it rapidly became clear that what the Junta meant by adherence to a ceasefire was, in reality, bloody retaliation. Even as the governments statement was distributed to journalists a pair of Argentinas most advanced aircraft, the French-built Super tendards, headed for the British task force carrying two of the countrys small stock of five lethal missiles, the name of which soon entered the English lexicon, the Exocet. As one of the pilots popped up from sea-skimming level to fix the target, the ship he locked on to was the destroyer HMS Sheffield . The results shocked Britain and the world. Twenty Royal Navy sailors died and the ship, which had cost 25 million in 1971, was wrecked and then lost when it sank while under tow.In Buenos Aires a jubilant Junta turned on the printing presses to rush out thousands of copies of a poster to rally the nation. It showed a Union Jack riddled with bullet holes and the legend, Fight to the Death. The glamorous Argentine news presenter, Magdalena Ruiz Guiaz, told me of her sorrow at the growing number of dead and injured but said, We are at the point of no return. The Juntas official spokesman Colonel Bernardo Menndez told me with jutting jaw that sovereignty over the islands No es negociable it is non-negotiable.The pugnacity of the Argentine Junta surprised many who did not know the recent history of the country. These were men who had been at war in a savage but little reported conflict for more than seven years and already had much blood on their hands. The Generals and senior officers were men who had ordered the torture and often the murder of leftist subversives whom they had kidnapped on the street or dragged from their homes. It was a Dirty War against many of their own people, a war that they regarded as a holy struggle against Marxist terrorism and which had extended into brutal suppression of all and every vestige of opposition in Argentina, be it in the form of terrorist gunmen, the leaders of organised labour, or intellectuals, many suspect in the eyes of the military for being Jewish, who advocated an alternative vision for the countrys future. Their victories against these opponents had bred hubris, with some in the Juntas leadership claiming that they had won the first battle of the Third World War.The terrorism they had set out to suppress was real enough. It was fuelled by repeated economic crises, with money rendered almost worthless by inflation rates of 500600%. This gave the terrorists relevance as they evolved into a peculiarly Argentine breed inspired, it was said, by the writings of the Marxist philosopher Frantz Fanon, who had delivered his infamous eulogy of terrorism: Violence frees the [individual] from his inferiority complex and makes him fearless and releases his self-respect. Terrorism is an act of growing up. The fact that Che Guevara was by origin an Argentine added some glamour to the cause.In the early 1970s Argentina was plunged into a dark tunnel of violent lawlessness. One of the key landmarks on the road to full-scale repression had been the shocking murder in 1974, when the elected civilian government of Isabel Pern was still in power, of Argentinas police chief Alberto Villar and his wife Elsa, killed by a bomb hidden aboard the cabin cruiser they used at weekends on the River Plate. Responsibility was claimed by the Montoneros, a left-wing group which proclaimed its allegiance to the now-dead dictator Juan Pern who had mobilised and motivated the working classes, but which was in fact one of the Marxist revolutionary groups surging throughout the Latin American continent, financing itself through highly lucrative acts of kidnapping and extortion. The police chief was known for carrying his own hand grenades on a belt around his waist but they were of little use on this occasion. The powerful explosion lifted the cabin cruiser 30 feet in the air and the bodies of Villar and his wife were found floating in the river.Operating in parallel and occasional competition was the Peoples Revolutionary Army or ERP, a smaller but well-organised Trotskyite group that believed in the propaganda of the deed. At an early stage they had tried to ignite a classic guerrilla war in the rural province of Tucumn in the north-west of the country but found themselves unable to match the Armys firepower and resorted to urban terrorism. Their attacks on the regime were fewer in number than those of the Montoneros but no less spectacular. They included a well-planned attempt in 1977 to assassinate the Juntas then leader, The same DIA document suggests that together the ERP and the Montoneros carried out well over 1,000 terrorist attacks between 1974 and 1979.General Jorge Videla had seized power in 1976 in the sixth military coup which Argentina had experienced since 1930. A three-man Junta made up of the heads of the Army, Navy and Air Force installed themselves, promising to restore stability. Videla had already made their intentions clear in a speech to the Conference of American Armies in the Chilean capital of Montevideo the year before. He said: As many people will die in Argentina as is necessary to achieve order.Once in power, Videla had tried to cultivate the image of a humble man who could save the country. But while the new military leaders sought at first to present an apparently reasonable image to the outside world, their security forces stepped up the already brutal campaign against the insurgent threat. Argentinas still functioning judicial system and conventional police forces were brushed aside in favour of special units using the crude tools of kidnapping, torture and murder. With an ideology embracing fierce nationalism extending at times into fascism and a fervent Catholic faith, the armed forces had always considered themselves the guardians of the Argentine flame. Now they set up what can only be described as a killing machine which dealt with its victims with frightening efficiency, turning them into a legion of the disappeared. It was a ruthless struggle in which a particularly murderous branch of the security forces was led by a violent career criminal who had earlier carried out one of the most spectacular bank robberies in Argentinas history and who joined the secret police directly from prison. He had been given the power of life and death over the perceived opponents of the Junta and it was he that we would encounter in that square in Buenos Aires.The progress from anti-terrorist operations to systematic secret slaughter was chronicled by a few brave journalists such as Robert Cox, the Editor of the English-language Buenos Aires Herald (now sadly defunct). Cox, who had settled in and loved Argentina, felt he had to leave the country in 1979 to save his life. The Dirty War was also brought to international attention by the growing number of mothers of the young men and women who for whatever reason had been targeted as suspect and vanished into the maw of the machine and who now demonstrated every week, becoming known as the Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo, after the square in front of the Presidential Palace where they gathered.The bloodshed was also systematically recorded by operatives of the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) reporting to Langley, Virginia from their offices at the US Embassy in Buenos Aires. Hundreds of their reports, including some dealing with our case, have now been released by the US government. The revelations they contain are at the heart of this book and what they make clear is that the CIA was extraordinarily well informed and able to follow the Dirty War on a virtually daily basis as the number of killings steadily mounted.The many events covered in this secret reporting included ghastly actions by the security forces near the small town of Pilar, a place with which we would soon become acquainted in terrifying circumstances. Pilar had become a macabre landmark, following the discovery soon after the Junta came to power of 30 mangled corpses in a field nearby. Twenty of the victims were male, ten female and The CIA report also described the reaction of the new President, General Videla: President Jorge Videla is annoyed that the bodies were left so prominently displayed and has ordered that this not occur in the future. Videla considers that such a type of situation reflects adversely on the good name of Argentina both within and outside the country. Videlas objection is not that the thirty people, who were purportedly involved with the Montoneros, were killed, but that the bodies appeared publicly. As the Dirty War progressed, many other security forces operations remained horrifyingly brazen. The released American documents include a graphic description of the kidnapping of several members of the Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo and two of their supporters, French nuns named Alice Domon and Lonie Duquet. On Saturday 10th [December 1977] Mrs Devisente was picked up a block from her house at 8.30 in the morning and thrown into a Ford Falcon kicking and screaming. Later in the same morning a French sister accompanied two gentlemen from her house and drove away with them. These abductions caused diplomatic protests from both the French government and the Vatican. The Argentine security services then arranged to supply the local press with photographs supposedly showing the two nuns in the hands of Montonero terrorists, although these were widely dismissed as fake. The US Embassy carried out its own investigation and Ambassador Raul Castro finally sent his report to Washington: A source informs the Embassy that the nuns were abducted by Argentine security agents and at some point were transferred to a prison located in the town of Junn which is about 150 miles west of Buenos Aires. Embassy also has confidential information obtained through an Argentine government source (protect) that seven bodies were discovered some weeks ago on the Atlantic beach near Mar del Plata. According to this source, the bodies were those of the two nuns and five mothers who disappeared between December 8 and December 10, 1977. Our source confirmed that these individuals were originally sequestered by members of the security forces acting under their broad mandate against terrorists and subversives. It was clear that, in spite of the professed Catholicism of the regime and its operatives, religion and even the Vaticans protests counted for little. In Buenos Aires gunmen targeted St Patricks church after a young priest, Father Alfredo Kelly, had preached about the need Attention focused on Argentina and the horrors taking place there when the country hosted the 1978 football World Cup. But the protests of human-rights groups were brushed aside as the bankrupt nation staged a spectacle which sent soccer-crazy Argentines wild with joy and captivated fans around the world. In front of President Videla and his guest of honour, the former US Secretary of State Henry Kissinger, whose support had long been of immense value to the Junta, Argentina triumphed in the final against Holland with Mario Kempes, the Matador, scoring two of Argentinas three goals. Meanwhile, outside the stadium, the number of victims continued to mount. The Junta finally admitted that 6,500 people were missing in its war. Amnesty International put the true figure at that stage at more than 25,000.By the turn of the decade the military were claiming victor y over the terrorist groups and the numbers of disappearances declined. But the Junta made no move to restore democracy. It was determined to hold on to power and knew no other way than the use of its secret police to suppress opposition. Even as General Galtieri sent troops to the Falklands and sought to motivate the nation for confrontation with Britain, teams of dirty warriors continued their work at home. We had a glimpse of their operations at a Peronist labour demonstration which, unusually, had been permitted by the regime in order to express support for its Malvinas campaign. In a square in the capital, several hundred people waved placards and chanted anti-British slogans as they laid wreaths at a monument to workers rights. On the fringes of the demonstration we saw a number of men dressed in suits sitting in several of the signature grey Ford Falcon cars. As it ended they got out and with cool self-assurance collected up a selection of the placards and leaflets that had been distributed among the crowd and wrote down the names of people who had signed the commemorative wreaths. Perhaps unwisely, we filmed them going about their business and then a short time later went to the scene of the latest known disappearance where, in a rundown street on the outskirts of the city, a young leftist called Anna Maria, pregnant with her soon-to-be-born child, had been kidnapped a few weeks before. Eight days after the kidnapping her body had been found nearby with two bullet wounds, one in the head, the other in the stomach. We filmed the location unaware as we did so that, according to the now-released CIA documents, we ourselves were under surveillance by the secret police.We had already met the man who was officially in command of much of Argentinas security apparatus, the Interior Minister, General Alfredo Saint-Jean. Unlike the famously bad-tempered Foreign Minister the grey-haired Saint-Jean was calm, almost avuncular, as he welcomed us in front of a large oil painting which adorned the wall of his office. A broad panorama, it showed uniformed sabre-wielding Argentine cavalry riding down fleeing Amerindians on one of the countrys vast open plains. The Minister explained with some satisfaction how the indigenous populations had been dealt with leading, he claimed, to the establishment of a coherent European-based society without ethnic discord. He then turned to the crisis with Britain.We are a peace-loving nation, he told me without a hint of irony, But dont misunderstand me. Argentinians will not renounce their rights to the islands. Argentina will negotiate but only as far as dignity will allow.Off-camera the Minister responded to our concerns about our own safety. He assured us that we were welcome in Argentina and that no one would interfere with our work. If you have any difficulties, telephone me here at the Ministry, he said, writing down his direct number on a piece of paper.But at that moment it was the Ministers repeated use of the word dignity that resonated and seemed a key to understanding the dictatorships behaviour in this crisis.With Argentinian troops preparing to defend their positions on the islands against what now seemed to be an inevitable British assault, defence of the nations dignity depended heavily on the pilots of the countrys motley collection of combat aircraft, organised in Air Force and Naval squadrons who alone could now challenge Britains supremacy at sea. These were the men that the Junta celebrated as its noblest fighters and they were to show the world another side of the uniquely contradictory Argentinian character, combining both the potential for savage brutality with a belief in courage and chivalry. Untried in aerial combat, they were to display bravery and skill that even the British task force commander, Admiral Sir John Sandy Woodward, would acknowledge. We felt a great admiration for what they did, he would later say.On May 12th, almost 500 miles from the capital of the Falklands, Port Stanley, at the Argentine Air Force base at Ro Gallegos near the windswept southern tip of the country, where bleak open spaces meet treeless horizons under grey leaden skies, ground crews were preparing eight jets for an attack on the British fleet. The planes were American-made Douglas A-4 Skyhawks, a design from the 1950s which had played an important role in the Vietnam War and in the Middle East, but was now becoming dated. Unable to carry any of Argentinas small stock of Exocet missiles, each Skyhawk was loaded with 500lb or 1,000lb unguided iron bombs, Second World War vintage weapons which had to be released at close range and would depend for success on the pilots bravery, skill and luck. Some of the aircraft were also in poor condition with their ejector seats known to be unreliable.First Lieutenant Fausto Gavazzi, recently married, was one of eight pilots suiting up for what some of his fellow officers believed would prove to be a suicide mission. In a chilling dress rehearsal hastily arranged as the British task force assembled, Gavazzis squadron had taken part in mock attacks on one of the two Type 42 destroyers that Britain had sold to the Argentine Navy in the 1970s. These ships, designed for an air-defence role, had recently been refitted with Seacat anti-aircraft missiles similar to those carried by the Royal Navy, and a series of low-level simulated bomb runs had shown the Skyhawks being repeatedly shot down by the system. However, in the attacks on May 1st Argentinian Dagger aircraft, originally Mirage V jets designed in France and assembled and sold to Argentina by Israel, had carried out low-level attacks on British ships. The bombs had missed and only inflicted limited damage and one of the Daggers had been shot down by a Harrier. However, the fact that they had got through to their targets had encouraged Argentine commanders to order major attacks by the Skyhawk pilots.On May 12th the plan was simple in conception but difficult and perilous to execute. After take-off the heavily laden Skyhawks would extend their range by refuelling from one of Argentinas two US-built KC-130 airborne tankers and then fly at sea-skimming level to find the British fleet. Though the weather was fine the pilots were to some extent flying in the dark. Without reliable long-range aerial reconnaissance they had only a general idea of where the British warships were. Radio messages from their troops in the Falklands, reporting that the British were now shelling them with their naval guns, suggested that there were ships quite close to the shore. The mission was to release their bombs at the closest range they could manage and then speed away at the lowest possible altitude before British missiles and guns could lock on and destroy them.On that day the word dignidad dignity was undoubtedly a powerful motivator for the men flying the Skyhawks but for me, lying in the footwell of the Ford Falcon with a cloth over my eyes and a gun to my head, I must admit that it was not the most urgent thought in my mind. Notes Sir John Nott autobiography, Here Today, Gone Tomorrow , Politicos Publishing, 2002. The British Invasion of the River Plate 18061807 , by Ben Hughes, Pen and Sword Books Ltd., 2013. The Fight for the Malvinas: Argentine Forces in the Falklands War , by Martin Middlebrook, Viking, 1989. US Defense Intelligence Agency report on International Terrorism dated March 30th, 1980. The Guardian , obituary, May 7th, 2013. CIA intelligence information cable, August 25th, 1976. Transcript of voice recording sent to US State Department by Embassy Human Rights Officer Allen Tex Harris, May 31st, 1978 (released 2017). The name of the lady who was kidnapped and subsequently disappeared was, in fact, Mrs De Vicenti, the error apparently being caused by faulty transcription of Tex Harriss recorded voice message to Washington. Telegram from US Ambassador Raul Castro to US State Department, March 30th, 1978 (released 2002). Dossier Secreto , by Martin Edwin Andersen, Westview Press Inc., p. 187.