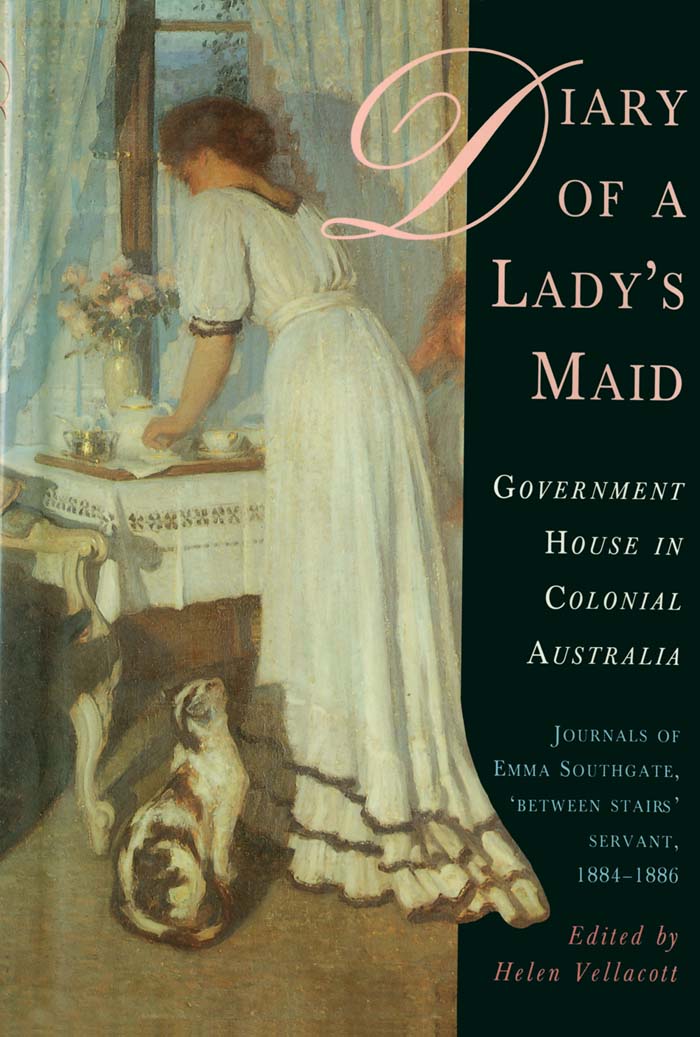

PREFACE

WHEN MY earlier book A Girl at Government House first appeared, I began to receive letters from all over Australia asking for more information about its heroine, Agnes. Which one of her suitors did she choose? This was the usual question. Some said they had sat up all night to come to the end of the story and were still left wondering. As the book was not on sale in England, it came as a surprise to get letters from there, from people who had presumably been sent the book by friends in Australia. The first of these was addressed to the publishers; it was on the notepaper of Lieutenant Colonel Charles Earle of Queen Camel, Yeovil, and commenced, GentlemenAs the grandson of Sir Henry and Lady Loch and the only son of Edith their elder daughter, A Girl at Government House gave me the greatest pleasure. It is so true to all the family lore I heard from my mother and grandmother. I have stayed at Government House with the Delacombes, so I was able to savour the very full diary of Lady Lochs maid which I possess. Thinking that the diary might be of interest to Australian Archives he had offered it to them, but the only person interested was the Tasmanian Archivist. Lieutenant Colonel Earle confessed that he did not know the diary writers name, but he could remember her giving the diary to his mother in the 1920s, and he offered his help if it were to be published.

Just as it took many years to discover the surname of the kitchen maid Agnes, and to trace her history, the details of Emmas life are proving even more elusive. Old census returns and ships passenger lists revealed only that her maiden name was Emma Southgate and that she had been born in England. From the diary itself we learn that she had her forty-ninth birthday during the voyage to Australia, but little else emerges.

Charles Earle and his wife asked me to spend a few days with them when I was in England, and when I reached Yeovil they drove me to their new house. I put new in inverted commas, for the Earles had recently moved from a large old manor house into a huge medieval tithe barn, its exterior revealing the huge timbers with which it was constructed, but its interior now converted into two spacious sets of apartments, complete with air conditioning and with every kind of electronic security device that can be imagined. It was prudent to have these devices for the Earles rooms were full of family treasures and other precious possessions. On the wall of the dining room, for instance, were two letters in frames, one from the Duke of Wellington and one from Lord Nelson, in the course of which he apologises for the uneven writing saying, It is but two weeks since the surgeon removed my right arm. When I admired these, Charles Earle said, Do you mind coming into the downstairs loo? And in here were two more frames of letters, apparently hung there because this room possessed the only blank walls left in the house. One large frame contained letters signed by every British sovereign from George I to the present day. The letters of the first two Georges, who usually spoke German, were written by an amanuensis and merely signed by them, but George IIIs was in his own clear flowing hand. Queen Victorias letter was written, of course, on notepaper with a wide black border, and the first to be typed was Edward VIIIs, thanking Colonel Earle for the splendid way in which the men of his regiment had kept watch round his fathers bier as he lay in State in Westminster Hall.

The Earles and I had several long talks about Emma and her diary, which they hoped to see published. Charles Earle said the name Southgate sounded familiar, though Lady Loch and her children always called her Titty. She had been with the family when the children were born, they all loved her, and presumably Titty was their first lisping attempt to say Pretty when she delighted them with colourful toys.

Lord Loch was another of Sir Henrys grandsons who helped with the diary. He had written to me about A Girl at Government House and when I was in England asked me to go across to their house, close to Stonehenge, for lunch. When the train pulled in, he was easily recognizedvery like pictures of his grandfather but more heavily built, and accompanied by a large, smooth-haired, black labrador, very similar, no doubt, to Benson, the familys labrador, who is mentioned frequently in Emmas diary. I evidently passed the luncheon test, for the Lochs very kindly asked me if I would be able to stay with them at their castle in Scotland, where many family treasures were in the library. It fitted in well with my journey to Edinburgh for the Festival, and before leaving Edinburgh I telephoned to confirm my travel arrangements. After I had spoken to Lord Loch he said, My wife is here and she would like to have a word with you. Lady Loch confided, We are looking forward to seeing you tonight, but be sure to have a bath before you come, we havent any water here, you know. Was I really going to the notoriously damp west coast of Scotland? But I need not have worried, for next day the spring that supplies water to the castle began to trickle again, and we were allowed to have baths as long as they were not deeper than two inches.

I spent happy hours in the library with the Lochs. It was full of interesting books and pictures, and I particularly enjoyed the huge old photograph albums with their excellent pictures of life in Victoria. Benson was often included in family photographs, but alas, there were no pictures of Titty. However, I did gain more insight into her time spent with the Lochs in Melbourne.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

My sincere thanks go to the many people who have helped me to amplify Emma Southgates diary and to find pictures of the many colourful characters whom we encounter in its pages.

It was Sir Henry Lochs grandson, the late Lieutenant Colonel Charles Earle, who first showed me the diary and expressed the hope that I would publish it, and I would like to thank his son, Richard Earle, for his continued help and encouragement, and Lady Loch for her interest and her help with illustrations.

My thanks also go to the staff of the British Library, the Cambridge City Library, the National Library in Canberra, the State Archives in Hobart, the La Trobe Library and the Parliamentary Library in Melbourne, the Mitchell Library in Sydney and the State Library in Adelaide, and to the librarians of Bendigo, Ballarat and Castlemaine, of the South African Library in Cape Town, the Archives of the Isle of Man, and the editor of Manx Life. It was the historical societies of Macedon, Gisborne, Warrnambool and Bairnsdale who were able to provide many of the details for this book. My thanks are due, too, to the many friends who have assisted me in gathering information, especially Judith Brown, Julia Vellacott, Mary Lloyd, Winifred Faulkner, Barbara Johnston, Mary and Miles Lewis, Jessie Serle, Jennifer Bleakley, Meg McArthur, Bet Stonehouse, the Reverend Neville Connell, Frank Cumbrae-Stewart, Geoffrey Stillwell, Kim Brownbill, Ian Smith and Wal Larsen.

I must thank especially Elizabeth Sherriden for coping so patiently with my untidy handwriting and for turning my pages of scrawl into a pile of immaculate typescript.