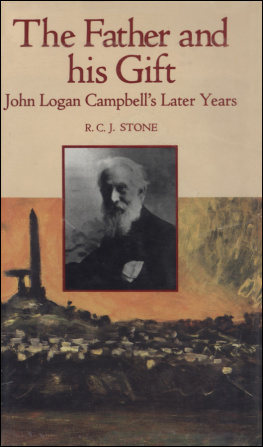

Here is the completion of the story of Sir John Logan Campbell, nineteenth-century businessman and benefactor, venerated in old age as the Father of Auckland.

At forty and newly married, Campbell had appeared to have achieved his ambition of leading an affluent and cultured life in Europe on the fruits of his enterprises in New Zealand.

This life depended on the continued profitability of the firm of Brown & Campbell. But dubious dealings by managers, some of whom Campbell believed used the firm as a milch cow, drove him back to Auckland; the challenge of commercial competitors and later a slump in business kept him there. For many years he struggled not only to keep his firm afloat but to preserve intact his One Tree Hill estate which in old age he had set his heart on bequeathing to the people of New Zealand. A revival in his business fortunes, however, enabled him to give the park before his death.

In 1901, the white-bearded, almost blind Campbell was elected Mayor of Auckland specifically to receive the royal visitor of that year, the Duke of Cornwall and York (later George V), to whom he presented the deeds of the newly named Cornwall Park. A statue of Campbell was erected in his lifetime, he was knighted, every public appearance was greeted with cheering. He had become the embodiment of Auckland.

Underneath there were disappointments. Three of his four children died young; the surviving daughter made a disastrous marriage. Campbell's own marriage suffered from his imperious temperament. His patronage of a young American sculptor soured. He disliked the fact that his prosperity increasingly depended on the liquor business, which was under fierce attack from prohibitionists.

The number and intimacy of the papers left by Campbell have enabled Professor Stone to bring his subject to life with the vivid touches of a novelist. Few New Zealand biographies are so rich in social and personal detail or give such varied private glimpses of a public man. This book and its predecessor, Young Logan Campbell, present a portrait of a Victorian colonist unrivalled in its scope and depth.

R.C.J. Stone is Associate-Professor of History at the University of Auckland. Young Logan Campbell, the first volume of his biography of Campbell, was published in 1982. He is also the author of Makers of Fortune (1973) and a recognized authority on nineteenth-century Auckland.

The painting on the jacket is One Tree Hill across the Manukau (1973) by Nigel Brown.

The photograph of Sir John Logan Campbell is reproduced by kind permission of the Cornwall Park Trustees.

eISBN 9 781 86940 016 3

THE FATHER

AND

HIS GIFT

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I N HIS first thirty-nine years, J.L. Campbell won fame as pioneer, merchant, and politician. Although in later life he remained prominent in business, his public role changed. He developed interests in art and philanthropy, and became regarded as the patriarch of Auckland.

Just as the emphasis of Campbells life altered, so did the character of the Campbell papers on which this biography of his later years is based. Business records still remain to the fore as late as the opening of the twentieth century. But personal and family papers become much more prominent. For once Campbell married he acquired what he called belongings, a wife and (later) children who, whenever separated by distance, wrote at great length to one another. These family papers provide an unusually valuable repository for social historian and biographer alike.

Campbell was an ardent archivist: he was also an enthusiastic autobiographer. From 1876 onwards he passed on to his family, his trustees, and posterity a wealth of reminiscences, memoirs, and memoranda (designed to put the record straight on disputed points); while, in advanced old age, he composed a lengthy autobiography. These writings together give an individual, and often partisan interpretation of his career. But A.O.J. Cockshutapplying the dictum of Leslie Stephen that an autobiography may well be more valuable in proportion to the amount of misrepresentation it containsreminds us that disproportions in such work are not to be thought of as blemishes, for they help to show what manner of man the autobiographer really was. Certainly in Campbells case his reminiscences, even those transmogrified into fiction, are deeply revealing of Campbell himself.

Over the twenty-three years I have studied the Campbell Papers I have built up a debt of gratitude to many people and institutions. I would draw attention once again to the acknowledgements of this debt already listed in Young Logan Campbell. Some thanks, however, are particular to this present book. I acknowledge the continued access to the Campbell Papers accorded me by the Sir John Logan Campbell Residuary Estate Trust Board. Enid Evans and Ian Thwaites, librarians of the Auckland Institute Library who have had charge of these papers over the years, have been unfailingly helpful; as have their staff, and of recent years I would single out Gordon Maitland as the one with whom I have worked most closely. The Auckland Public Library also assisted by putting the Mackelvie Papers at my disposal. The Turnbull Library helped me in my task in various ways over many years. Roger Blackley of the Auckland Art Gallery has guided me on the art history of Auckland. Bodies who put papers generously at my disposal were the Cornwall Park Trust, Nicholson Gribbin & Co. and The Campbell & Ehrenfried Company Ltd. I deeply appreciate the support and enthusiasm which sustained me in my drawn-out task provided by Sir Kenneth B. Myers of Auckland, and by Sir Colin Campbell, collateral descendant of Sir John Logan Campbell, and present baronet of Aberuchill and Kilbryde. Sir Harold Acton who now occupies Villa La Pietra, one of Campbells homes in Tuscany, generously helped me in 1974.

I have a deep debt to John Stacpoole of Auckland and G.C. Dunstall of the University of Canterbury. In each case their researches on J.T. Mackelvie were put at my disposal.

The University of Auckland has contributed much to this book. Twice I was granted leave and money to travel to Europe to carry out research into Campbells life there. There have been other grants of money for research trips within New Zealand as well. Three successive heads of the History DepartmentProfessors Sir Keith Sinclair, Nicholas Tarling and Keith Sorrensonhave fostered me in what (one imagines) they may have thought had become an obsession. I am deeply grateful, too, for the accurate work and cheerful assistance of the typing and secretarial staff.

Augusta Ford continued to assist me, as she did for my volume on Campbells earlier life, by twice reading my manuscript to suggest where I could write more clearly. My wife Mary, who has shared my interest in Campbell, has helped and supported me in innumerable ways.

![Logan - Sprout lands [Release date Mar. 26, 2019] : tending the endless gift of trees](/uploads/posts/book/128344/thumbs/logan-sprout-lands-release-date-mar-26-2019.jpg)