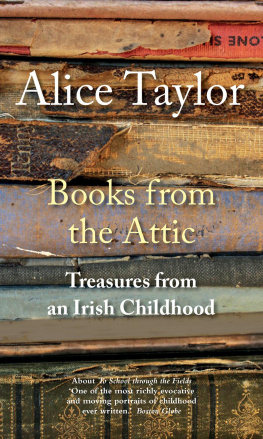

People read Alice Taylors books, people crave Alice Taylors company because they want to find peace. They find it in the leaves of her books and the folds of her laughter.

Ireland on Sunday

In Ireland, where scribblers are ten a penny, she has become the most popular and universally loved author in memory.

Mail on Sunday

To read Alice is to grow in mental health. Hibernia

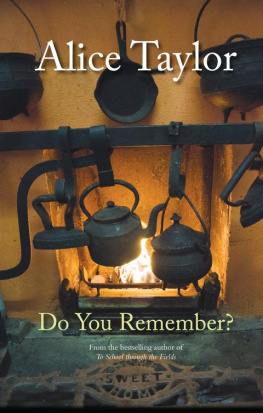

MOST RECENT BOOKS FROM ALICE TAYLOR

And Time Stood Still

The Gift of a Garden

For a full list see www.obrien.ie

I n the nineteen eighties I wrote a story. It was the celebration of a childhood. It was my story. But it turned out to be the story of many people, linked across three generations: the older generation who had lived through it, the middle generation who had experienced the tail-end of it, and the younger generation who had seen it through the eyes of parents and grandparents. They all looked into a remembering mirror, caught glimpses of their own story and wanted to step inside. So they walked into bookshops all over the country and turned To School through the Fields into the biggest bestseller ever published in Ireland.

A multitude of seeds sprout a book. This one had gestated in my head for many years. It originally took root in there on beautiful May mornings as I watched baby calves get their first taste of freedom and race down sunlit fields. It brooded as we picked potatoes on freezing days with clods of earth clinging to our knees. It glowed on beholding untouched pristine snowfields on winter mornings. It wept on the death of my baby brother Connie, and my old friend Bill. It danced as we listened on summer nights to the corncrake as we drifted off to sleep. It glowed as we gathered with neighbours around our kitchen table to celebrate Mass in the age-old custom of the Stations. It continued to glow as I watched my parents walk the fields and bless them with Holy Water on Rogation Day. It mourned when we buried an old farm horse who had been a family friend. It rekindled as we drank tea in the meadow beside the river on summer days.

The womb of this book was the farm and old house where I was born. Eight generations of our family have lived there. And during my childhood, family members who had emigrated came back from all over the world to the ancestral home. It matters not whether your ancestral home is a small cottage or a rambling castle, it is still the nurturing cradle of your family roots, and buried deep within our core is an inbuilt need to come back to the place from whence we came a bit like the wild salmon. Those people who returned to walk the fields of their ancestors left a lasting impression on me. They were warmly welcomed by my parents, but I regretted even then that no ancestor had taken it upon themselves to write about their way of life. Famous and historic people and events are recorded, but often not so the life of ordinary people. Yet we too tell the story of a time.

Another inspiration for this book was my children. When my children, like others all around the country, went on holidays to their grandparents on home farms, which by then had many modern amenities, they loved the way of life and came home full of stories.

When I explained that previous generations had grown up there with no bathroom, no car, no telephone and no television I could see that they were unable to imagine what that could be like. It felt as if I was weaving fiction. That made me realise that a whole generation had grown up with no idea of how their parents and previous generations had lived. And that was only in the space of one generation!

So I decided that rather than have us studied in later times like a prehistoric species by a student doing a thesis, our story should be told by one of ourselves. By someone who had run to school through muddy gaps, who had watched with wonder as baby chicks cracked their way out of hatching eggs, who had stayed up all night minding bonhams and in the early hours had watched with wonder the sun rise over the Kerry mountains while listening to the magic of the dawn chorus.

Another reason for writing the book popped up one day in an auction room when a pair of beautifully framed photographs of an elegantly dressed couple was one lot to be auctioned. It set me wondering: these were somebodys parents or grandparents, and given the way this photograph was so expensively and carefully framed, there was no way that these people ever imagined themselves coming under the hammer! Can you ever be sure what the generations after you will do? Also at that time, there was an antique shop in Cork with a slogan that read Come in and buy what your grandmother threw out, and in todays world we are forever moving house so nothing is hoarded in attics for the perusal of the next generation. So, publishing my childhood story would preserve it for posterity.

I sent the manuscript to Brandon. Why Brandon? I knew very little about publishers, but I had just read The Bodhrn Maker by John B Keane that man of many plays and on it I saw the name Brandon; and I also loved the idea of a publishing house called after a Kerry mountain! So it was posted in the spring of 1987. Then I went away for two weeks and on my return the son who had been in charge of operations in our absence told me that a letter had come, but he couldnt find it! So I wasnt sure if Brandon had responded positively or not until I got an irate phone call from the publisher, Steve MacDonogh, enquiring as to why I had not responded to his letter. We met up the following day and I knew that he was impressed, but he asked me to lengthen the manuscript, telling me, You are writing about a world that is very familiar to you but people may read this who never heard of many of the practices that you are describing, so go into more detail.

He was right, because later this book was translated into many languages. One of the first was German, and a German woman who visited me told me that during the war she had been farmed out to a family deep in the country and now, years later, it was the one place in the world where she could feel at home; she needed to go back there occasionally and she loved the similarities with my story. When I asked the Japanese translator how come the Japanese were interested, she told me that they too had left behind a forgotten world. Perhaps childhood, animals and nature are universal themes.

The writing of further details posed no problem and I assured Steve that when I was ready I would be back. Deadlines were not on my agenda as writing is a hobby that I love, and I did not want it to become a pressure point which would kill the joy. After Christmas 1988 we went to print and it was published on 14 May of the same year.

The first rule in marketing is getting the product known out there. At that time the voice of Ireland on radio and TV was Gay Byrne, and I appeared with him on both media. When I asked Gay privately how he understood this book so well he assured me that in Dublin too he had seen huge changes in lifestyle. Gay was the ultimate interviewer and always asked the question that was hovering on the mind of the nation, and he was a great listener too, not feeling threatened by silence while he waited for an answer, and should an interview go off the planned path he was not afraid to step into the unknown. He had the ear of the country and through him so had I, and it got To School through the Fields off to a flying start.

Why did my story strike a chord with so many people? It could be that it told a story hitherto unscripted of a people who had worked the land and considered themselves very ordinary. They were, in fact, extraordinary! In