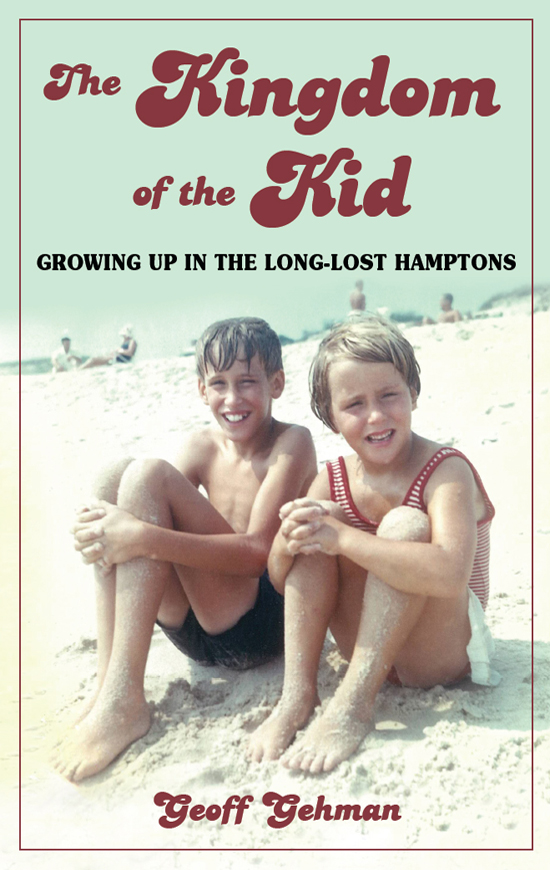

Cover: The author, then 10, and his sister Meg, 6, on the author's favorite beach by Beach Lane in Wainscott, Long Island, September 1968. (Gehman Family Collection)

Published by State University of New York Press, Albany

2013 Geoff Gehman

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America

No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission. No part of this book may be stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means including electronic, electrostatic, magnetic tape, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without the prior permission in writing of the publisher.

Excelsior Editions is an imprint of State University of New York Press

For information, contact State University of New York Press, Albany, NY

www.sunypress.edu

Production by Diane Ganeles

Marketing by Kate McDonnell

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Gehman, Geoff.

The kingdom of the kid : growing up in the long-lost Hamptons / Geoff Gehman.

pages cm. (Excelsior editions)

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN 978-1-4384-4784-1

1. Gehman, GeoffChildhood and youth. 2. Hamptons (N.Y.)Biography. 3. BoysNew York (State)HamptonsBiography. 4. Hamptons (N.Y.)Social life and customs20th century. 5. Middle class familiesNew York (State)HamptonsHistory20th century. I. Title.

F127.S9G44 2013

974.7'21dc23

2012045680

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Special Deliveries

Lobsters lined up for a race on the Kaufman porch, winner to be dunked first in a pot of boiling water, August 1967. Lobster handlers are, from left, the author, Whitley Kaufman, Meg Gehman, Clayton Kaufman. (Photo courtesy of Clay Kaufman)

I n the summer of 1969 astronauts opened the moon, Woodstock rockers closed the New York State Thruway, and I began delivering the U.S. mail with Yaz.

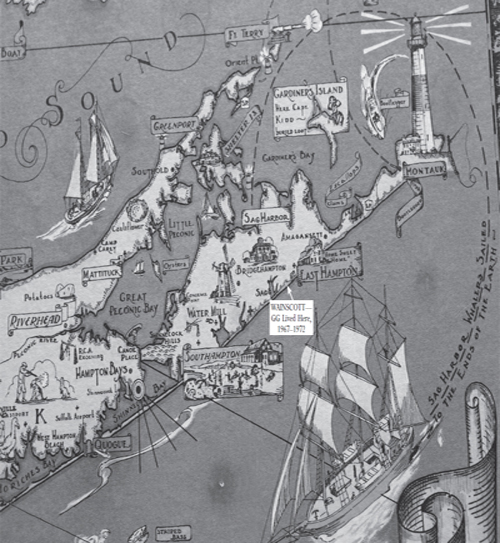

The route, and routine, was virtually the same virtually every morning in Wainscott, N.Y, a hamlet of 500-odd folks on Long Island's South Fork, the farm community and beach resort also known as the East End and commonly called the Hamptons. First I hopped on my Stingray bicycle, the one with the banana seat and the spokes clipped with eight years of baseball cards starring Carl YastrzemskiBridgehampton native, Boston Red Sox hero and my first role model who wasn't my parents. Then I crossed Whitney Lane to the Graves' newspaper box to borrow their Newsday to check Yaz's latest box score. After returning the paper to its proper place, I cycled to the main drag, Sayre's Path, a slightly humped, lightly sandy lane splitting woods of scrub oak and fields of potatoes. Pumping furiously, I passed the screened porch where Paul McCartney played guitar during his early months as an ex-Beatle and the yard where a well-off, well-oiled Scottish chauffeur named Pete Morrison toasted the sunset by playing Amazing Grace on bagpipes.

At the end of the path I stopped to soak in the fabulously wet, amazingly graceful South Fork light, which bounces off the Atlantic Ocean and a half-dozen other kinds of waterway, turning the sky into a sea of silky scrim and everything else into crisply outlined islands. Turning right onto Main Street, the rare main street in America without a single working store, I pedaled by maples and lindens planted after the 1938 hurricane, three centuries' worth of six architectural styles, a potato-dairy-strawberry farm owned by a family who came here from southern England in the northern half of the seventeenth century, and a nineteenth-century church that began life as a Bridgehampton school. Beyond the chapel was a holy quartet of earthy landmarks: a rectangular cemetery where I learned to meditate on mortality; a rectangular baseball field where I hit foul balls off gravestones as a member of the Wainscott Wildcats; a one-room school house where my wildcat sister contemplated her misbehavior in a trash can, and a dead general store I resurrected with my imagination.

Near the western end of Main Street I parked by a shingled cottage that served as a one-room post office. After removing the mail from our box, I saluted postmistress Ethel Pierson, a former New York City teacher with a remarkable collection of seashells and life preservers and a husband who was a carpenter comic. (Asked why the post-office flag flew at half-mast, Sam Pierson quipped: For the death of the three-cent stamp.) Before leaving the premises I scanned the FBI's most-wanted list, memorizing the frightening faces of violent criminals just in case I met them roaming Beach Lane beach, disguised in sunglasses, bathing suits and tans.

Back on the Stingray, I turned left onto Town Line Road, detouring to a new house that resembled two old walls. A cross between an avant-garde castle and the back of a huge fireplace, it could have been built by masons from outer space. After staring in awe for a few minutes, I scooted around the corner and down Main Street, where, picking up speed on the straightaway by Wainscott Pond, I dreamed I was driver Mark Donohue attacking the Bridgehampton Race Circuit, a wicked serpentine of blind bends blocked by dunes.

At the eastern end of Main Street I sped across the finish line, the open gate of the Georgica Association, a colony founded in the 1880s by wealthy, sweaty Manhattanites seeking free air conditioning from summer sea breezes. I cycled through a forest seemingly imported from the Adirondacks; past the coved creeks of Georgica Pond, a tidal swimming pool for the likes of Carlos Montoya, the famous flamenco guitarist; around the softball field and former golf link where I turned double plays with my father; along the tennis courts where Dad hustled me in the shadow of a windmill moved from Montauk and Wainscott; over the speed bumps that made me a daredevil; through the prairie meadow that made me a naturalist; past a grove of wind-gnarled trees where I camped and fell asleep to the ocean's whispering hiss.

Back outside the association's entrance I zipped by a Kentucky antebellum mansion owned by cosmetics queen Estee Lauder; buttonhooked right onto Wainscott Stone Road, where actor Elliott Gould rented a house to escape the pressure of M*A*S*H fame; hung a left onto Wainscott North West Road, nicknamed Turtle Road for the turtles that waddled from the woods during rains, and hung another left onto Roxbury Lane, passing steeply slanted houses called saltboxes, built in the sixties by Wesley D. Miller, a real-estate cowboy with a 10-gallon hat. I turned right onto Foxcroft Lane, a major artery in the Miller-developed Westwoods and Wainscott's best playground. There I shot the shit with my best friend Mike Raffel, fellow baseball nut, rock n roll guru and guardian of The Forum, a street basketball court with Wainscott's only street lamp south of the Montauk Highway, rigged on the sly by Mike's lineman father.