Table of Contents

To Heather, For reminding me that there is also music

Prologue

I moved slowly down the walkway, outwardly anxious, wanting to rush ahead, but blocked by the mass of people before me. Secretly, I was happy with the slow pace of the crowd, because I was not really sure how I would handle what was waiting.

The darkness to my left kept growing, the sense of being pulled into gloom and death was stronger with each step, and soon I had to stop anyway. There were too many panels, bearing too many names I remembered, and I wouldnt pass any of them without a brief pause, to reflect, to remember.

After a while it was almost over. There was only one left.

I stopped, knelt, wiped some accumulated grime off the name, and used every bit of strength I had to keep my emotions in check. Marines dont cry. He had taught me that. But it wasnt supposed to end like this. None of it was supposed to end like this. We were supposed to be the victors. And, given everything we had done, I still couldnt understand why we werent.

We hadnt lost. We hadnt been beaten. So why had I spent the last decade and more hearing us referred to as losers or suckers who had fought for a lost cause every time the subject came up?

Maybe it was because the country and the media just didnt know what had really happened. Maybe its time they learn.

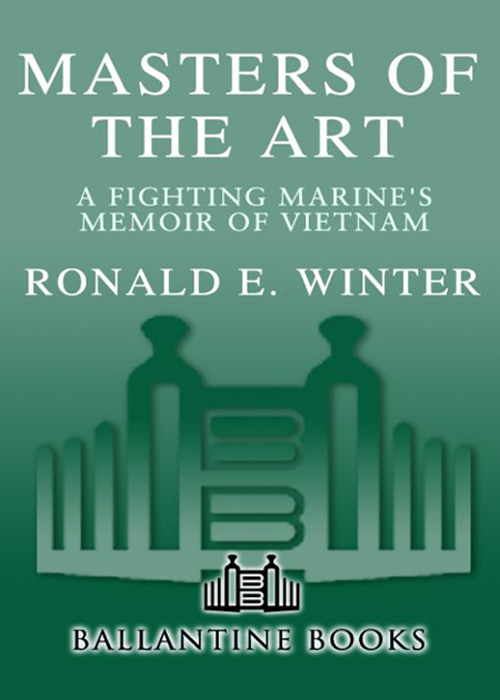

This book is about war and fighting, about people who do the fighting even when they arent sure why, and about staying true to a cause, even if it is not popular.

It is about life, and death, and futility, and hope. It is about surviving and teaching. But above all, it is about a group of men who joined forces in 1966 in North Carolina and stayed together for the most part until 1969.

It is about their actions, individually and collectively, in that time. They, or we, were United States Marines, assigned to what became Medium Helicopter Squadron 161 (HMM-161). We were commanded most of that time by Lt. Col. Paul W. Niesen, who was promoted to full colonel and named Marine Aviator of the Year in 1969, just after our time together ended.

But that was after Parris Island, after North Carolina, and after Vietnam. Most of us were quite young back then, in our late teens or early twenties, and those who survived are now grown men, working in a different environment than the one we trained for and went to in 1968. Weve gone on to other endeavors, and we dont even look much like we did then.

Butoutside of my familythe people I met in 161, and one other, have had a greater impact on my life than anyone I have encountered since.

This book is intended as a reminder of what we did there, because it was significant. It was lost temporarily in the larger picture of the war, the protests, Watergate, and the fall of Saigon in 1975.

But it will not remain lost. There was too much that was too important and should be passed on. It is for the survivors, and about them, but it is also about those members of 161, and one other, who didnt survive, because their deaths should not go unnoticed.

Some of the incidents are sad, some are tragic, some are funny, but all are true and represent my best recollections, aided by Marine Corps records and the recollections of other former members of 161.

This isnt intended as an exact history. It is a tribute.

Because back then we lived together, worked together, fought together, looked out for each other, and didnt let each other down. Finding people who live up to that standard in the years since we last saw each other has been hard to do. But I havent forgotten, the others havent, either, and I wont let them down now.

But first, I have to tell you how it started for me. And I have to tell you about Starbuck.

Books published by the Random House Publishing Group are available at quantity discounts on bulk purchases for premium, educational, fund-raising, and special sales use, For details, please call 1-800-733-3000.

PART I

Chapter 1

My first impression of Sgt. Robert F. Starbuck was a worms-eye view of the soles of his boots. They came crashing through the double swinging doors in the middle of the Parris Island Recruit Receiving Barracks at about 3:00 a.m. January 14, 1966.

I was sitting on the floor of a squad bay along with eighty-four other recruits, having been told to do so by the sergeant major of Parris Island, who had left us there only a minute before.

Then there was a rumbling noise, like thunder, or maybe a herd of buffalo on a rampage, and Starbuck kicked through the door, both feet off the floor. He saw us sitting there and his face turned to a twisted, red picture of pure anger.

Get up, get the fuck up. Get on your goddamn feet. Whotold you maggots to sit down? Get up! His voice had the depth of a bottomless well and the pitch of an acre of gravel.

Starbuck was six feet tall and about 185 pounds. He had legs like tree trunks and a perfectly V-shaped upper body, with wide shoulders and a narrow waist. His head was shaved damn near as closely as ours were, because he wanted it thatway. Starbuck looked like what Id expect a U.S. Marine drill instructor to look like.

Im sure that thought went through my mind at the time, but it took second place to one other thought.

He was pissed! Somebody made the mistake of trying to say, But the sergeant major told us...

Shut your hole, maggot. I dont want to see your green teeth or smell your rotten breath.

That was just the beginning. Right behind Starbuck was a short black corporal named Jonathon L. Sparks, and he was carrying a footlong piece of iron pipe. A long, lean staff sergeant, whose name I cant remember, rounded out the trio.

They were all yelling like madmen, and nothing could be said or done correctly.

It was a setup of course. We had arrived on the island at about midnight, after a bus trip from Charleston, South Carolina, where I had gotten off the train that had brought me from the North. There I joined what was to be the rest of my platoon. A few guys who thought they were smarter than everyone else had been drinking in the back of the bus on the way. They paid later.

When we stopped at the receiving barracks, a drill instructor named Sergeant Wilson came on board, laughed a minute with the driver, and then turned on us like a wolverine.

You maggots have ten seconds to get off this bus, he bellowed. Im going to count down from ten. Anyone left whenI get to zero is going to die. Now move!

Talk about people scrambling. The fun was abruptly over. He kept counting, and believe it or not we all made it. Outside it was more of the same. Line up. Stand straight. Close it up. Toe to heel. Dick to tail. Asshole to belly button.

The terminology was unquestionably different than anything Id been exposed to previously.

The country needed a lot more Marines in 1966 than it had, thanks to Vietnam, and there was no delay in processing us. In the next three hours we stripped, showered, had all our hair cut off, identification pictures taken, and uniforms issued. We were given seabags for stowing our extra uniforms and other gear, and we packed away our civilian clothes. All contraband was confiscated, and I sneaked a small laugh when they found a pack of rubbers in one guys pocket.

What the hell do you think youre going to do with these here? was the obvious question.

Next page