AN EXTRAORDINARY

BIOGRAPHY.

A GALLERY OF

ASTONISHING

ARTWORK.

THE LEGACY OF A

MADMAN.

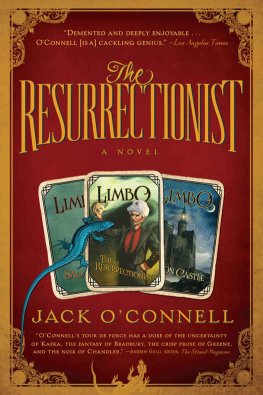

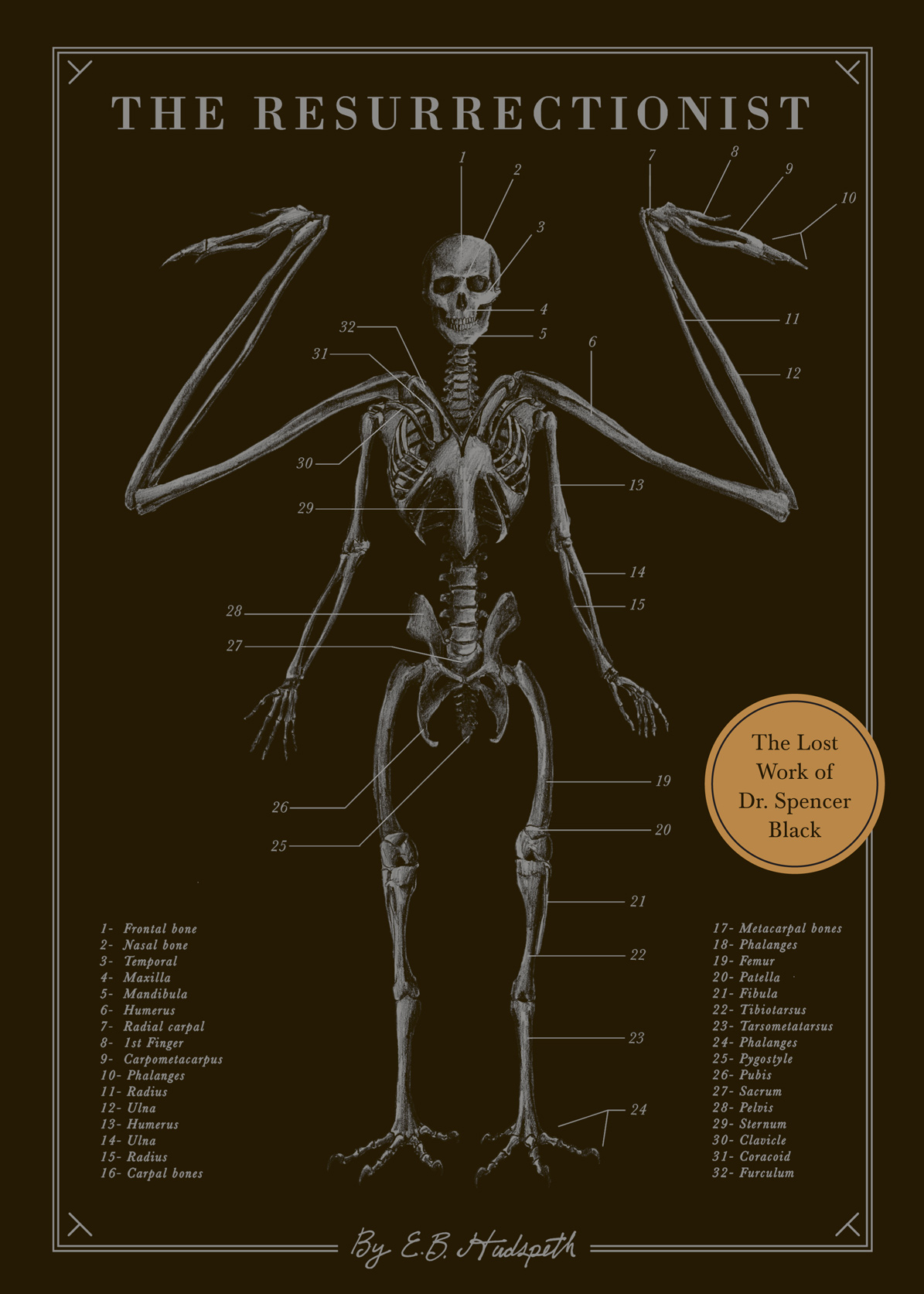

Philadelphia, the late 1870s. A city of gas lamps, cobblestone streets, and horse-drawn carriagesand home to the controversial surgeon Dr. Spencer Black. The son of a grave robber, young Dr. Black studies at Philadelphias esteemed Academy of Medicine, where he develops an unconventional hypothesis: What if the worlds most celebrated mythological beastsmermaids, minotaurs, and satyrswere in fact the evolutionary ancestors of humankind?

The Resurrectionist offers two extraordinary books in one. The first is a fictional biography of Dr. Spencer Black, from a childhood spent exhuming corpses through his medical training, his travels with carnivals, and the mysterious disappearance at the end of his life. The second book is Blacks magnum opus: The Codex Extinct Ammalia, a Grays Anatomy for mythological beastsdragons, centaurs, Pegasus, Cerberusall rendered in meticulously detailed anatomical illustrations. You need only look at these images to realize they are the work of a madman. The Resurrectionist tells his story.

Copyright 2013 by Eric Hudspeth

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without written permission from the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Number: 2012934523

Hardcover ISBN: 978-1-59474-616-1

eBook ISBN: 978-1-59474-624-6

Designed by Doogie Horner

Production management by John J. McGurk

Quirk Books

215 Church Street

Philadelphia, PA 19106

quirkbooks.com

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

v3.1

A N OTE FROM THE P UBLISHER

THIS BOOK WOULD NOT exist without the tireless efforts and generous financial support of Philadelphias Museum of Medical Antiquities.

Over the past fifteen years, their curators have toured private collections throughout the United States and Europe in search of the lost journals, letters, and illustrations of Dr. Spencer Black, one of the most remarkable physicians and scientific mavericks Western civilization has ever known.

As most physicians and students of medicine undoubtedly already know, Dr. Black achieved fame and notoriety in the late nineteenth century for his pioneering work in treating genetic abnormalities. No one disputes that Dr. Black was a genuine prodigy; before he had even reached the age of twenty-one, his work was known by surgeons around the world. And yet this professional acclaim was short-lived. Much of Dr. Blacks later work remains shrouded in controversy, rumors, and whispers of blasphemous abominations. Thanks to the materials collected herein, we now know that Dr. Blacks personal and professional exploits were far more scandalous than anything found in the gothic novels that were popular during his lifetime.

Many of the letters and illustrations in this book were donated from the estate of Dr. Blacks brother, Bernard. These materials have been unseen since the International Convention of Modern Science in 1938 (where their display was fleeting, because of public disapproval). Other letters, journals, and drawings have come to us directly from anonymous donors, and these are published here for the first time. They offer startling new insights into the doctors personal life and professional achievements.

This publication begins with the most complete biography to date of the Western worlds most controversial surgeon. It is followed by a near-complete reproduction of Dr. Blacks magnum opus, The Codex Extinct Animalia.

Together, these two extraordinary documents are the definitive study of Dr. Spencer Black. They are The Resurrectionist.

18511868

C HILDHOOD

In my childish imagination, Gods wrathful arm was

ever-ready and ever-present.

Spencer Black

D r. Spencer Black and his older brother, Bernard, were born in Boston, Massachusetts, in 1851 and 1848, respectively. They were the sons of the renowned surgeon Gregory Black. Their mother, Meredith Black, died while delivering Spencer; her passing caused a great unrest in both boys throughout their childhood.

Gregory Black was a respected professor of anatomy at the Medical Arts College of Boston. He conducted dissections for students at a time when cadavers were scarce and anatomists depended on grave-robbing resurrectionists to further their research. He had some of his favorite cadavers preserved, dressed, and propped up in a macabre anthropomorphic display in his office. As one of the citys leading professors, with an increasing number of students every year, his demand for bodies surpassed the legal supply. He was one of the primary purchasers of stolen cadavers in the area, and he dug up many additional bodies himself, with the assistance of his two young sons. Spencer Black writes at length about these experiences in his journals.

I was no older than eleven when the ordeal began. The night I remember above all, I was hurried out of bed after my brother, Bernard: my elder by three years. He was always stirred awake first so he could help prepare the horse and tie up the cart.

Hours before dawn, in the cool of the night, we walked away from our home and went down to the river where we could cross a bridge; beyond which the road was dark and obscured, an excellent place to enter and leave the cemetery unnoticed.

We were all quiet, for calling attention to ourselves would have done us no service. It was damp and wet that night: it had rained earlier and I could smell water still fresh in the air. We slowly moved along the bridge. I remember the wheels of the cart, straining and creaking, threatening to arouse the nearby residents and their curiosities with just one sudden noise. Steam rose off our aged horse. The mist of her breath was comforting; she was an innocent creatureour accomplice. The narrow stream below, too dark to see, trickled quietly. Any sound that we made with our dreary march was muted as soon as we crossed the bridge and went over the moss-covered earth framing the cemetery. Once inside the perimeter my father was at ease, his humor improved, and with a calm gaiety he led us to a newly established residence for some deceased soul. They called us resurrectionists, grave robbers.

When I was a child I hadnt the conviction against the belief in God that I have now. My father was not a religious man, however my grandparents were, and they gave me a rigorous theological education. I was very much afraid of what we did those nights; of all the terrible sins a man might commit, stealing the dead seemed among the worst. In my childish imagination, Gods wrathful arm was ever-ready and ever-present. And yet I feared my father even more than I feared my God.

My father reminded us there was no cause for trepidation or fear. He would repeat these things as we dug through the night, as the smell of the bodys decay rose around us. Soon we reached the soft, damp, wood coffin of Jasper Earl Werthy. The wood cracked, releasing more of deaths repugnant odor. I put my spade down, grateful that my father was wrenching the wood and freeing the body himself, sparing us this task. Jaspers face was a sunken gray mask; his skin was like a rotten orange. This is how I came to understand my fathers profession.