DEDICATION

To those Italian men and women who, beyond rational explanation, rose during the Nazi Occupation from submission to heroism without leaving home.

First published in Great Britain in 1995 by

LEO COOPER

190 Shaftesbury Avenue, London WC2H 8JL

an imprint of

Pen & Sword Books Ltd,

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire S70 2AS

William C Simpson, 1995

A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 0 85052 475 X

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, in any form

or by any means, without permission from the publishers.

Typeset by Acorn Bookwork, Salisbury, Wilts

Printed by

Redwood Books Ltd, Trowbridge, Wilts.

To prepare for incidents bordering on the ridiculous but nevertheless true, the reader is entitled to the following background.

Upon returning from Italy to Britain and leaving the Army in the summer of 1946, I was retraining with my pre-war employer, Royal Insurance Company in Liverpool, prior to a scheduled posting to New York, when on the Mersey ferry I ran into a typist who, in A.T.S. uniform, had worked with me in Rome.

Still weighed down by the events from the moment of escape in Nazi-occupied Abruzzi through the underground life in Gestapo-controlled Rome and two intense but exhilarating years immersed in the follow-through Allied Screening Commission, I needed to unburden in order to focus on the future.

In frequent evening sessions with my ex-secretary and her notebooks, I poured it out. Somehow she completed the typed volume before I boarded the Queen Elizabeth in March, 1947. It was not a literary event, but the result was an exhaustive record of happenings, names, places, times and clearly-recalled dialogue, starting from the Italian surrender to the Allies on 8 September 1943.

In New York the information lay dormant for years. In 1993, after gentle prodding from my wife and my son, I dropped all and wrote.

Two long British Intelligence reports (WO204/1012 and WO208/3396) entitled The Activities of the British Organization in Rome for Assisting Allied Escaped Prisoners of War which, thanks to the Thirty Year Rule on public security, have now been downgraded from Top Secret, provide abundant, if cold, authentication for the veracity of this book. Those reports, compiled from interrogation by the appropriate Intelligence Branch in Allied Forces Headquarters in Italy, are now available in the Public Record Office at Kew and, with their ample statistics, constitute a massive footnote for the scholar.

This story incorporates only essential statistics. My intent rather is to draw the reader into the taut atmosphere of this moment-to-moment underground existence. While the exploits of a somewhat cavalier group of British and American officers and their audacious Italian accomplices may have been uniquely colourful with the backdrop of Rome itself and the Vatican, the reader by projection can begin to comprehend the Odyssey of 75,000 Allied prisoners let loose in Italy, and wonder at the wave of humanity which greeted them.

By virtue of adherence to fact, many emerging characters do not continue throughout, particularly as the scene moves abruptly from Abruzzi to Rome.

I acknowledge the generous co-operation of:

Staff of the Public Record Office, Kew, near London.

Tomaso Bracci and Tullio Zucaro, archivists of Il Tempo, Rome.

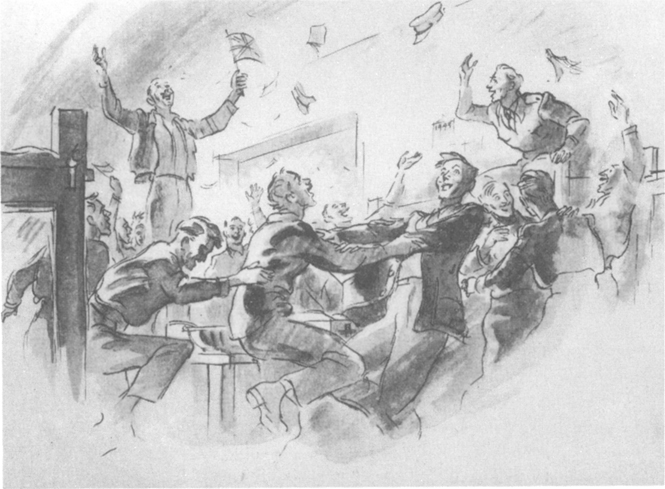

Artist Gordon Horner of Horam, E. Sussex for kind permission to reprint sketches from his book, For You The War Is Over. London, 1948.

Colonel Samuel I. Derry, DSO, MC, for kind permission to reproduce two photographs from his book, Rome Escape Line, London, 1961, and New York, 1961.

A Crown copyright excerpt is reproduced by kind permission of Her Majestys Stationery Office.

I am greatly indebted to Mrs Dorothy Marcinek of Bayville, N.Y., for her superb secretarial performance in word-processing the manuscript and with unfailing good humour performing myriad related tasks. Special thanks to my wife, Sally, for her encouragement, tolerance of domestic adjustments, and editorial hints.

Apologies to my chocolate Lab Barney for shortened walks.

In July, 1943, Allied armour overran Sicily, fresh from defeating the German Afrika Korps in Tunisia. In Rome dissident Italian Government ministers prodded King Vittorio Emanuele III to take a bold step. On 27 July the King removed the Fascist Duce Benito Mussolini from office and abducted him to Abruzzi. To head the Italian Government, the King appointed Marshal Pietro Badoglio, the conqueror of Ethiopia in 1936.

On 8 September, 1943, as British invading forces gained footholds on the southern tip of the Italian mainland and American forces prepared to land at Salerno, Marshal Badoglio and the Italian King declared an unconditional surrender of their country to the Allies and fled south to Allied territory.

In the ensuing military vacuum Italian military depots and installations closed down. Hundreds of thousands of conscripted Italian soldiers simply quit and went home. Among them were units assigned to guard duty at seventy Prisoner of War camps containing 75,000 Allied officers and men. Of these the majority, from British Commonwealth countries, had been captured by the German Afrika Korps over two years of desert warfare from Egypt to Morocco. 1500 Americans were mostly US Army Air Force personnel downed pilots and their crews.

Since Nazi Germany maintained no garrison in the country of its Axis partner, Fascist Italy, the citizens of Rome and of other towns in Central Italy anticipated nothing worse than a brief period of nebulous German influence before the triumphant arrival of Allied armies which were expected to advance unopposed right up the leg of Italy in a matter of weeks at the most.

With good reason, a similar optimism permeated the ranks of every POW camp. By secret methods a coded order from the British War Office had successfully reached the senior British officer of each camp: in the event of an Italian capitulation all POWs should stay put within the camp to await the early arrival of Allied ground forces.

In reality, an incensed German Fhrer, despite preoccupation with threatening military reverses in Russia, began to pour two German armies into southern Italy within days of the Armistice. Their divisions formed a defence line in the mountains east and west of Cassino which was to withstand the might of Allied attacks through the entire winter of 1943/44. With equal speed Nazi Schutzstaffel or SS battalions occupied Rome and took control of its state government apparatus. Soon they blanketed the city with an ominous panoply of security.

Optimism across central Italy faded. In the capital city Romans submitted to a despairing ordeal of German police control, of Gestapo surveillance, raids and brutality.