2009 by Mickey Friedman

All rights reserved

Manufactured in the United States of America

1 2 3 4 5 c p 5 4 3 2 1

This book is printed on acid-free paper.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Friedman, Mickey.

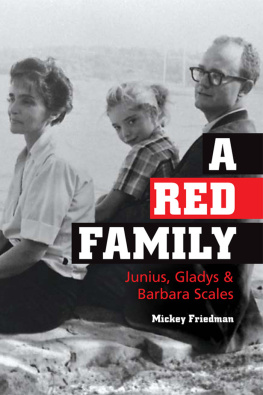

A red family : Junius, Gladys, and Barbara Scales / Mickey Friedman with an afterword by Barbara Scales and historical essay by Gail Williams OBrien.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-252-03396-4 (cloth : alk. paper)

ISBN 978-0-252-07604-6 (pbk. : alk. paper)

1. Scales, Junius Irving.

2. Scales, Gladys.

3. Scales, Barbara.

4. CommunistsUnited StatesBiography.

5. CommunismUnited StatesHistory20th century.

I. OBrien, Gail Williams II. Title.

HX84.S4F75 2009

335.4092273dc22 2008032932

To Barbaras parents, and to mine.PREFACE

Mickey Friedman

This is the story of a Red family: Junius, Gladys, and Barbara Scales. Red in the older sense of the word. Because, before there were red and blue states, there were the Reds, the Communists.

Junius Scales was the son of one of the wealthiest families in North Carolina. He left privilege to live in a poor textile-mill village, and in 1939, on his nineteenth birthday, he joined the American Communist Party (CPUSA). One of the few publicly known Communists in the South, Junius organized textile workers, fought segregation, went underground, evaded the FBI, was indicted, arrested, unsuccessfully appealed his conviction to the Supreme Court, and went to prison.

Gladys Scales came to Communism from a very different place. She was born in Brooklyn, New York. Her Jewish father was a successful small businessman who lost everything in the Depression. As her family fell apart around her and she battled her own depression, Communism offered the opportunity to imagine and work for a more caring world.

By the time their daughter Barbara was born, Junius and Gladys were under siege and anti-Communism shaped American politics. In an attempt to protect her and allow her the chance for a more normal childhood, they didnt tell Barbara that she was a red-diaper baby.

A Red Family is an oral history, a familys account of their rich and complicated journey in American radical politics. Its a story few Americans know, a part of our history that is rarely talked about.

Many others have tried to analyze the Communist movement in greater depth: Theodore Draper; Irving Howe and Lewis Coser; David Shannon; Nathan In the last several decades, writing about and analyzing American Communism has become a popular pastime. I recently found a list of more than eight thousand scholarly books and articles about the Party.

A Red Family is based on interviews conducted with the Scaleses beginning in March 1971. Except for a single session with Junius when Barbara was present, the interviews were conducted individually to preserve spontaneity and to capture their separate recollections. Each session, recorded on a simple cassette machine, lasted three to four hours; Junius, Gladys, and Barbara were each interviewed three or four different times.

Let me be clear: I was not then, nor am I now, a historian. I was, and continue to be, a writer, and more recently a filmmaker and political activist. Perhaps a professional historian would have asked different questions and elicited different answers.

But I am, like Barbara, a red-diaper baby, so the book was very important to me for reasons I thought I knew then and, after a decade of therapy, for reasons I better understand now.

Unlike Barbara, I always knew about my fathers politics. He took me to May Day parades in Union Square; I went with him to the offices of the Daily Worker, the newspaper of the Communist Party, where he was an editor. If I was fairly obedient, Id come home with a photo of Jackie Robinson, the Communist Partys favorite ballplayer. It wasnt by accident that even though I grew up in the Bronx, I rooted for the Yankees arch rivals, the Brooklyn Dodgers, the team that integrated baseball.

I couldnt escape the reality of my fathers politics: from the ever-present FBI men assigned to follow him on Kingsbridge Road (and their occasional attempts to get me to talk about my dad) to our tapped telephone. There was no getting off the extraordinary tightrope I had to walk. Proud, like most sons of their fathers, I had been sworn to secrecy. I could never talk about the Party or my fathers job. Printer was the magic answer to any question about what he did for a living.

Children arent meant to live double lives, but I got to be good at it. Except for a first-grade slip that landed me on the wooden bench outside the principals office, I kept the secret until college. My father, already out of the Party for four years, was called to testify before the House Un-American Activities Committee, and his appearance made it to the New York newspapers.

For me, the cold war was anything but cold; it was ferocious and unrelenting. For most Americans, my father and Communists like Junius were the enemy. All you had to do was watch an episode of I Led Three Lives on televisionand those were the days when just about anything that made it to television was regarded as near-truth. Each new episode from 1953 to 1956 seemed more diabolical than the last. Those TV Communists were masters of deception, skilled in assassination, bomb making, and industrial sabotage. When it came to insidious treachery, those guys would give Osama bin Laden a run for his money.

Older readers might remember the movie The Invasion of the Body Snatchers, with its evil, alien cadre whose pods grow replacement mothers and fathers and sisters and brothers. Younger readers have their own version: the synthetic Cylons of Battlestar Galactica. During the cold war, the Communists were Body Snatchers and Cylons, and unlike the swarthy Islamofascist-extremists of todays terror nightmares, they looked like ordinary Americans. Communists could blend in undetected: they taught in local schools, worked beside you in the office or factory, served in the army, went bowling. Yet, according to the myth, what they wanted most was to take away everything Americans loved best: liberty and freedom, the right to worship God, progress and individual initiative, and the opportunity to succeed.

As you will see, Junius and Gladys were nothing like those caricatures. Nor was my father.

And so, for personal and political reasons, I wanted Americans to hear another side of the story. I wanted A Red Family to be something other than traditional history: a conversational book, with the sense and sound of life stories being sharedthe Communist experience from the inside out.

I wanted Junius, Gladys, and Barbara to speak from the heart. I also wanted the feminine perspective. At that time, books about politics and political life primarily came from men, and we didnt often enough hear the voices of women. But most of all, I wanted and needed to make Communists real, to help a Red family make itself known to other American families. With plain talk, I hoped to bridge the political divide and move past a large backlog of ignorance and bias about the Left.

This book is printed on acid-free paper.

This book is printed on acid-free paper.