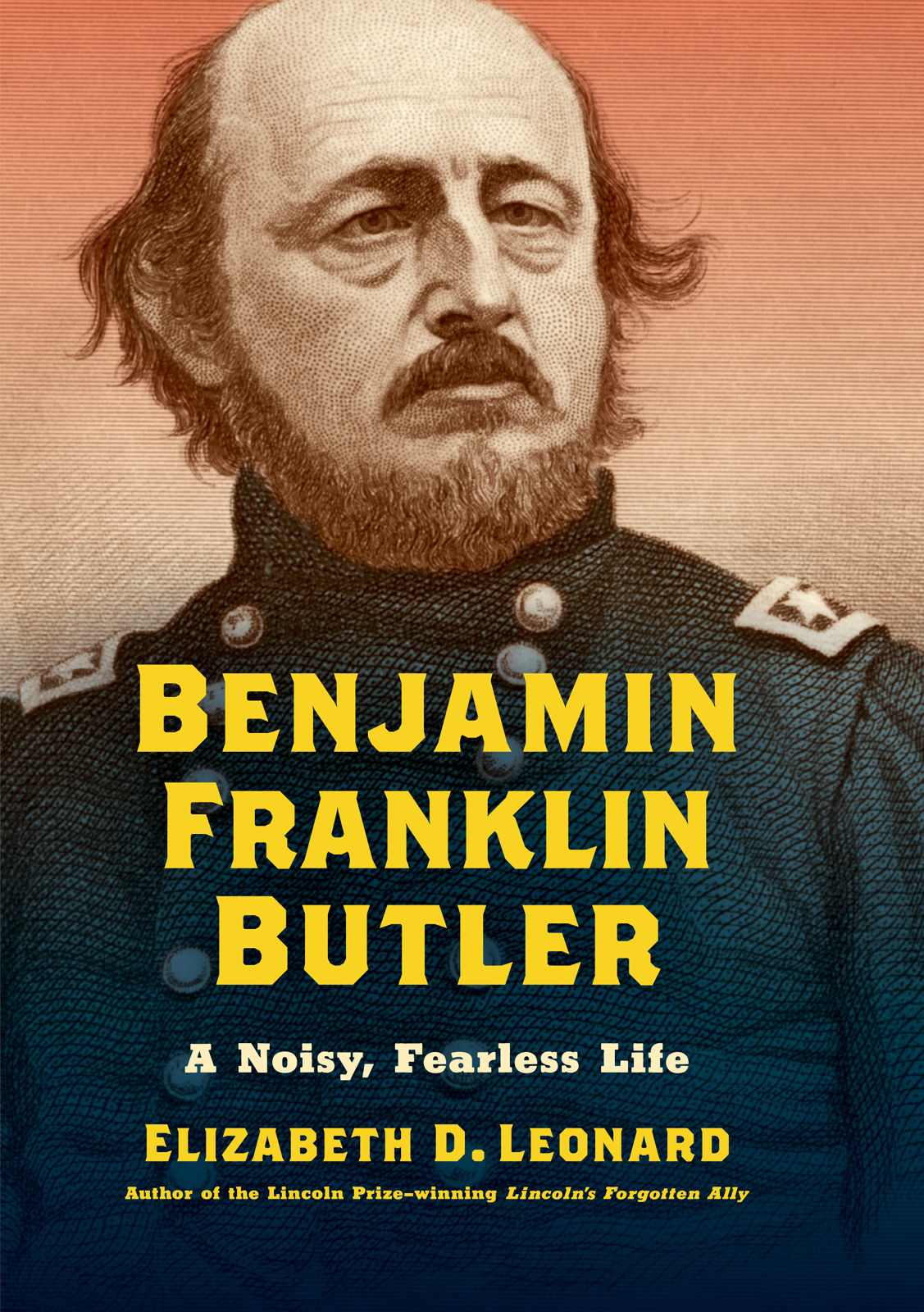

He was a noisy and fearless advocate of radical causes including the rights of organized labor, woman suffrage, greenback currency, and public ownership of railroads. In the Civil War he was an enthusiastic supporter of arming Blacks and in Reconstruction he fought for their civil rights long after other politicians had given up. He was usually the champion of the underprivileged and managed to offend almost every established interest in nineteenth-century America.

HISTORIAN HAROLD B. RAYMOND, THE BEAST AT THE TOP OF THE STAIRS, APRIL 1977

Preface

MEMORY

Benjamin Franklin

Butler

Jurist Soldier Statesman

Patriot

His talents were devoted to

the service of his country

and the advancement of his

fellow men

So begins the epitaph on the massive headstone that marks Benjamin Franklin Butlers grave at the Hildreth Family Cemetery in Lowell, Massachusetts. Next come details about his birth, marriage, and death, and then these words: The true touchstone of civil liberty is not that all men are equal but that every man has the right to be the equal of every other man if he can.

It is not known who devised this weighty affirmation, but it seems likely that Butler crafted it himself. Certainly he would have endorsed the statement as a clear expression of what became the guiding principle of his life and work, namely, that regardless of class or race or other defining characteristic at birth, all men (and today Butler surely would have included and women) deserve a level playing field on which to strive for success. The epitaph as a whole also encapsulates Butlers commitment to the idea that performing ones civic duty means helping ensure equal opportunity for all, as he had tried to do unless, of course (a point left implicit), those seeking help werelike Confederates during the Civil Warguilty of trying to destroy the United States.

How accurately the sentiments expressed in this epitaph reflect the reality of Butlers life, work, and purpose has long been a matter of debate. Even during his lifetime, Butler was a highly controversial figure who made a very great impression on the public interest, and not always in a positive sense. Maine Republican James Blaine reportedly once described Butler as an original and picturesque individual with a talent for turbulence. And in the century and more since his death in January 1893, the memory of what kind of person Butler really was, and what motivations truly underlay his actions as a lawyer, politician, and soldiereven as a husband and fatherhas taken various forms. In 1918, in response to the recent publication of his Private and Official Correspondence, one journalist observed wryly that the late general has not had the best of reputations among us. No man of his era, wrote another reviewer, has been more cussed and discussed than Butler, who, a third reviewer declared, had a natural propensity to make the form and manner of his actions as offensive as possible. He was a general without capacity, a man without character, sneered the industrialist, self-professed wartime copperhead, one-time president of the American Historical Association, and author of a multivolume history of the United States, James Ford Rhodes, during the Massachusetts state legislatures 1914 hearings regarding the possible erection of a statue to Butler in Boston. Such harsh depictions of Butler have been both abundant and persistent; enduring caricatures have attacked him as mercurial, arrogant, tyrannical, incompetent, duplicitous, and/or driven purely by greed and ego. Indeed, down to the present some of the nicknames that have dogged him most tenaciously are Beast, Damnedest Yankee, Devil, Spoons, and Stormy Petrel.

Among those who began the process of memorializing Butler was, perhaps not surprisingly, the man himself, whose massive and, it must be said, largely (but not exclusively) self-congratulatory 1,100 -page-long Autobiography and Personal Reminiscences (colloquially known as Butlers Book) appeared in 1892. Butlers passing the following year yielded widely ranging assessments from those who knew (or claimed to have known) him in various settings. Gen. Butler had a stormy career, one journalist wrote simply, upon learning of the former generals death. Another quoted one of Butlers former congressional colleagues as saying, colorfully, He was like a volcano with the smoke just curling out of the top, but which might break forth in a seething torrent of fire and smoke at any moment. He was a man of most contradictory qualities, remarked the Rev. Dr. William H. Thomas in the eulogy he gave at Lowells St. Pauls Methodist Episcopal Church on the evening before Butlers public funeral. To say that he was not always great nor great in everything is to say that he never attained what never has been attained. Rather, Thomas continued, Butler was full of weaknesses and inconsistencies, a man of like infirmities with other men, whose friends, even, would never assert that in his headlong pursuit of success he was always scrupulous to use only such means as would be approved by the accepted standards of ethics. Indeed, Thomas added, Butler would not claim so himself. Butlers ego was certainly robust, but so was his sense of humor, and he often demonstrated a striking and, among major historical figures, refreshing capacity for candid and critical self-reflection.