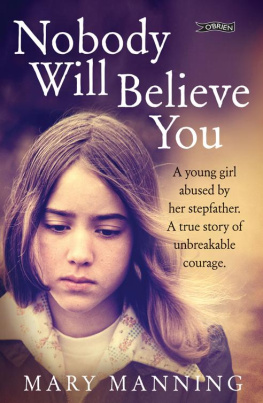

Dublin, Ireland

19 July 1984

T he day started like any other. I slept through my alarm only to be woken by Mam hollering loudly up the stairs of our house in Kilmainham.

It took you long enough to get this job, Mary. Could you not try hanging on to it?

This was Mams favourite line, which really made no sense at all because, having started off part-time in Dunnes Stores, I had now worked there full-time for nearly two and a half years. With little interest in moving I slowly opened my eyes to find my two great loves staring down at me Patch, my dog, who wed got when I was eight years old, sitting protectively on the bed, and above her on the wall, Bruce Springsteen! Footsteps padded softly up the stairs and I smiled to myself I knew it was my Da. He popped his head around the bedroom door and, out of earshot of Mam, whispered that if I got myself out of the bed quick enough he would make me a rasher sandwich. I was the youngest and only girl of three siblings and he still treated me like his baby. By the time I made it downstairs, Mam had already gone to her cleaning job and Da was putting the final touches to my breakfast. I grabbed it, ran out the front door and across the street to catch the No. 78 bus which brought me to the city centre. I normally enjoyed the quiet solitude of my short bus journey into work but the last few mornings had been filled with a sense of growing unease. A huge row was brewing between our union, the Irish Distributive Administrative Trade Union (IDATU), and the management of the Henry Street branch of Dunnes Stores where I worked. They were constantly at loggerheads over the ill treatment of the shopworkers; issues such as lack of toilet breaks, excessive disciplinary action over till receipts, unreasonable working hours and we had been trying to get a meeting with management for weeks but this new row was entirely different and escalating at a rate none of us had anticipated.

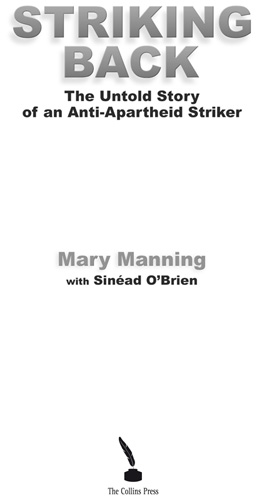

The general secretary of our union John Mitchell had handed down a directive instructing all IDATU members not to handle the sale of South African goods in their place of work. John Mitchell, fairly new to the job, was a Cork man with radical views. He was involved in the Irish Anti-Apartheid Movement and had been secretary in 1981 for the campaign against Irish Rugby teams tour of South Africa that year. IDATU was considered one of the most conservative unions in Ireland at the time and Mitchells ideas were deemed new and unusual within the executive. In the beginning, they indulged the more harmless-looking motions, for example, the motion on apartheid. At that time it was fashionable to pass motions banning South African goods, and nobody would ever speak against it. The difference was that John Mitchell implemented the ban.

In reaction to this, our boss, Ben Dunne Jnr, the managing director of Dunnes Stores, instructed his management that all staff had to handle the sale of South African goods. In recent days, management in our branch in Henry Street had been summoning all IDATU shopworkers individually to the office and warning them that any refusal to sell the South African produce would be met with serious consequences, possibly even the loss of employment. Only the day beforehand my colleague Michelle Gavin had been let off with a final warning after she refused to register a sale.

Summer was unusually hot in Ireland that year and I was already sticky with sweat from the humid bus journey by the time I made it into the city centre. Walking over the Hapenny Bridge, I paused to stare down the River Liffey, mentally gearing myself up for a day of work.

In the distance I saw Karen Gearon, our shop steward, and called out to her. As we sauntered towards Henry Street more shopworkers arrived from different directions and strolled along with us, all of us gossiping about the day ahead. By the time we reached the staff entrance to Dunnes, we all knew that today would be eventful. None of us was too worried, though.

John Mitchell, the general secretary of our union, IDATU, pictured here addressing an anti-apartheid rally in 1984 ( Derek Speirs) .

In fact, the feeling amongst the thirty or so of us in the changing room was unusually chirpy that morning. This was 1984 and we were all young women so our conversations mainly revolved around hair. There was no such thing as hair too huge so perms, puffed-up styles and waves dominated much of conversation, both inside and outside work. But as the time approached to go out on the shop floor the chat turned to the day at hand. With the support of the union and this new directive we might finally have an opportunity to give a long overdue middle finger to our boss, Ben Dunne, and his management.

The mouthy, cocksure attitude of the boisterous changing room evaporated as we entered the shop floor. I took my position at one of the tills as usual, but what was unusual was the line of managers standing behind us. There were so many of them; too many for them all to belong to our store. They had been drafted in from other branches to deal with this situation in a show of power.

Glancing up and down the line of cash registers I suddenly realised that every one of us put on the tills that morning was an IDATU member. The shop was beginning to fill with customers so it was only a matter of time before one of us would be tested. I was aware that, in comparison to other branches of the Dunnes Stores chain, the Henry Street branch had a particularly hostile relationship with their staff but what was happening here felt very heavy-handed and intimidating.

Immediately the mundane task of stacking shelves, which I normally despised, intensified in its appeal. My palms started sweating as I opened up my cash register. Everything after this happened very quickly. I spotted a middle-aged woman in the distance with two large yellow grapefruits in her basket. My heartbeat increased at the sight of them. I avoided eye contact and popped my head down straight away. Please dont come to me, please go to any other till, I thought to myself, but the woman plonked her basket at my till, completely oblivious to the internal crisis unfolding within me. Politely, I informed her that because of an instruction from my union, which was opposed to the importation of goods produced under the apartheid regime, I was unable to register the sale of South African goods today.

@strikingbackmm1

@strikingbackmm1