Dedication

For Sara Laschever, my hero

Contents

When two great Saints meet, it is a humbling experience. The long battles to prove he was a saint...

PAUL MCCARTNEY, DEDICATION TO T WO V IRGINS , 1968

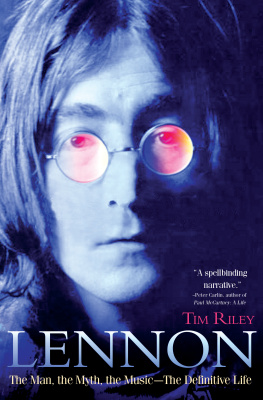

W hen John Lennon presented his fellow beatles with the cover art for Unfinished Music No. 1: Two Virgins in November of 1968, everybody recoiled. McCartneys quote sat beneath Lennon and his lover, Yoko Ono, holding hands naked in their bedroom with postcoital grins. EMIs lordly chairman, Sir Joseph Lockwood, refused to distribute the record, pronouncing John and Yoko ugly. In America, Capitol Records balked, and even when the album was shipped through an independent distributor, New Jersey authorities confiscated thirty thousand copies, declaring the cover obscene. Controversy subsumed the records experimental sounds. Nobody could understand why Lennon would deliberately extend the public-relations debacle he had already created by leaving his British wife and child for the Japanese-American conceptual artist, especially on the eve of the first Beatles album in eighteen months, the double White Album (originally The Beatles ).

Time has papered over the photographs insolence: Lennon was pouring acid on the Beatle myth, demonstrating how shallow and ridiculous pop stardom seemed even as his band hit new creative peaks. This would be just the first of many media campaigns he waged to kick his way out of the Beatles.

That July of 1968, when this insouciant photograph was taken, the Beatles were slogging through the poisonous White Album sessions that prompted EMI engineer Geoff Emerick to quit in a huff. Drummer Ringo Starr walked out soon thereafter. The Lennon and McCartney songwriting collaboration had long since trailed off into independent work, even though the songs still bore the trademark Lennon-McCartney authorship. Increasingly, their partnership had graduated from aesthetic one-upmanship to outright conflict: in that same hectic period, the band vetoed Lennons first rendition of Revolution as too slow, and even the blazing remake sat on the flip side of McCartneys Hey Jude, the bands revitalizing summer single.

To the others, this widening rift coincided with Yoko Onos divisive presence. Lennon could not have chosen a more passive-aggressive way to disrupt the groups chemistry. Yoko planted herself not only at recording sessions but at private group demos and Apple business meetings, offering comments as if she were a de facto member of the band. Not even the Beatle wives had ever been granted such access. She roamed the EMI studios unfettered, without so much as an introduction to George Martin, the bands producer.

But whatever resentments among the band, the bond between Lennon and Ono was already immune to protest.

By now, some forty years after the groups breakup, the Lennon legend has graduated into myth of an entirely different order than the one that turned him into an international rock star, the one he retired from for the last five years of his life to raise his son Sean. On the radio, he sings to us from some idealized Tower of Song, frozen in time and memory like Buddy Holly or Eddie Cochran, those creative martyrs who haunted his own impressionable adolescence.

The remaining three Beatles reunited in the mid-1990s to tell their own version of their story with the Anthology video and book, the bands story tunneled into nostalgia. In 2000, the greatest-hits album became the fastest-selling CD in history, reached number one in twenty-eight countries, and went on to sell more than thirty-one million copies worldwide, the best-selling album of the decade in the United States. At decades end, the Beatles became the best-selling band of the new millennium. (This would be the last release guitarist George Harrison oversaw directly; he died in November of 2001.) In 2006, the Cirque du Soleils Love began selling out six shows a week in a Las Vegas theater with a customized sound system by producer George Martin and his son, Giles. Its remashed sound track became still another huge hit.

Lennons own story, of course, had passed through rocks looking glass long before. He hovered over every frame of the Anthology, and his familiar quotes heaved with subtext: it was hard to imagine Lennon participating in such a whitewashed, sentimental project devoted to enshrining a myth he had done so much to puncture during his lifetime. His post-Beatle revolts linked the personal with the aesthetic: he first ran off with Yoko Ono, then married her the week after McCartney married Linda Eastman, then howled at the demise of the Beatles (on 1970s blistering Plastic Ono Band ) even as he subtly helped to engineer it. He rebuilt his peacenik/politico faade while ridiculing his former partner McCartney (in How Do You Sleep?), before careening into a hackneyed drunken-celebrity lost weekend in the early 1970s. Finally, after winning a long immigration battle with the Nixon administration, he washed up onto the shores of storybook monogamy and parenthood during a five-year sabbatical. His assassination in 1980 quelled Beatle reunion rumors, but only temporarily.

In the fall of 2009, the Beatles entire sixties recording catalog was remastered in luminous digital audio, updating the flat CD mixes that had circulated since the late 1980s. These joint releases sent both Lennons myth and his Beatle legacy into yet another orbit, reigniting stalwart fans and breeding a vast young listenership. Scholars who had studied these recordings for decades suddenly heard previously unnoticed details, alongside a new vocal and instrumental physicality. New ideas came to the fore, and lingering contradictions commanded fresh attention. The finely blended close harmonies on This Boy and Nowhere Man took on new immediacy; McCartneys guitar solos on Taxman and Good Morning Good Morning suddenly seemed richer, grittier, and downright contemporary. Alongside elaborately detailed sessionographies like The Complete Beatles Recording Sessions by Mark Lewisohn (1992) and Recording the Beatles by Kevin Ryan and Brian Kehew (2006), these remasters confirmed how profoundly the Lennon-McCartney recording catalog transcended its era.

Britons have come to rank the Beatles just after Shakespeare as a core element of their national identity, but few feel challenged to explain how a rock career, once cultures most defiled profession, now sits comfortably next to one of Western cultures highest achievements. Lennons childhood is generally known to be traumatic, but even some of the better biographers give his primal separation scene (between his father, Alfred Lennon, and his mother, Julia Stanley Lennon, in an uncles Blackpool home in June of 1946) a paragraph at most. This black hole of emotional loss swallows up all his intimacies. He spent his life adopting father figures and mourning his mother, who died in an accident when he was seventeen. I lost my mother twice, he once said; and like a lot of his lyrics, these words are truer than many fans appreciate.

In many of his key intimate relationshipswith songwriting partner Paul McCartney, manager Brian Epstein, drummer Ringo Starr, and first wife Cynthia PowellLennon balanced alliances with fragile affections; he seemed to spend almost two-thirds of his Beatle tenure surrounded by people he wished to avoid. As his first marriage fell apart, Lennons reliance on McCartney also began to fall away, even as McCartneys support for his eccentricities strengthened. (One intriguing subtext of Hey Jude involves McCartneys affection for Cynthia and his fatherly sympathy toward Julian.) Their showbiz feud over control of their publishing catalog belies their friendship. And Lennons influence on McCartney is far more pronounced, and remarked upon, than McCartneys subtler influence on Lennon. As they entered their epic feud, Lennon made sure Ringo Starr drummed on his 1970 divorce album, Plastic Ono Band; but Lennon never appeared on a single McCartney solo album, or vice versa.

Next page