Contents

Guide

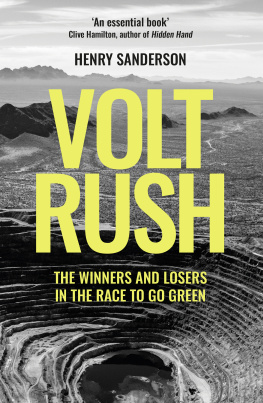

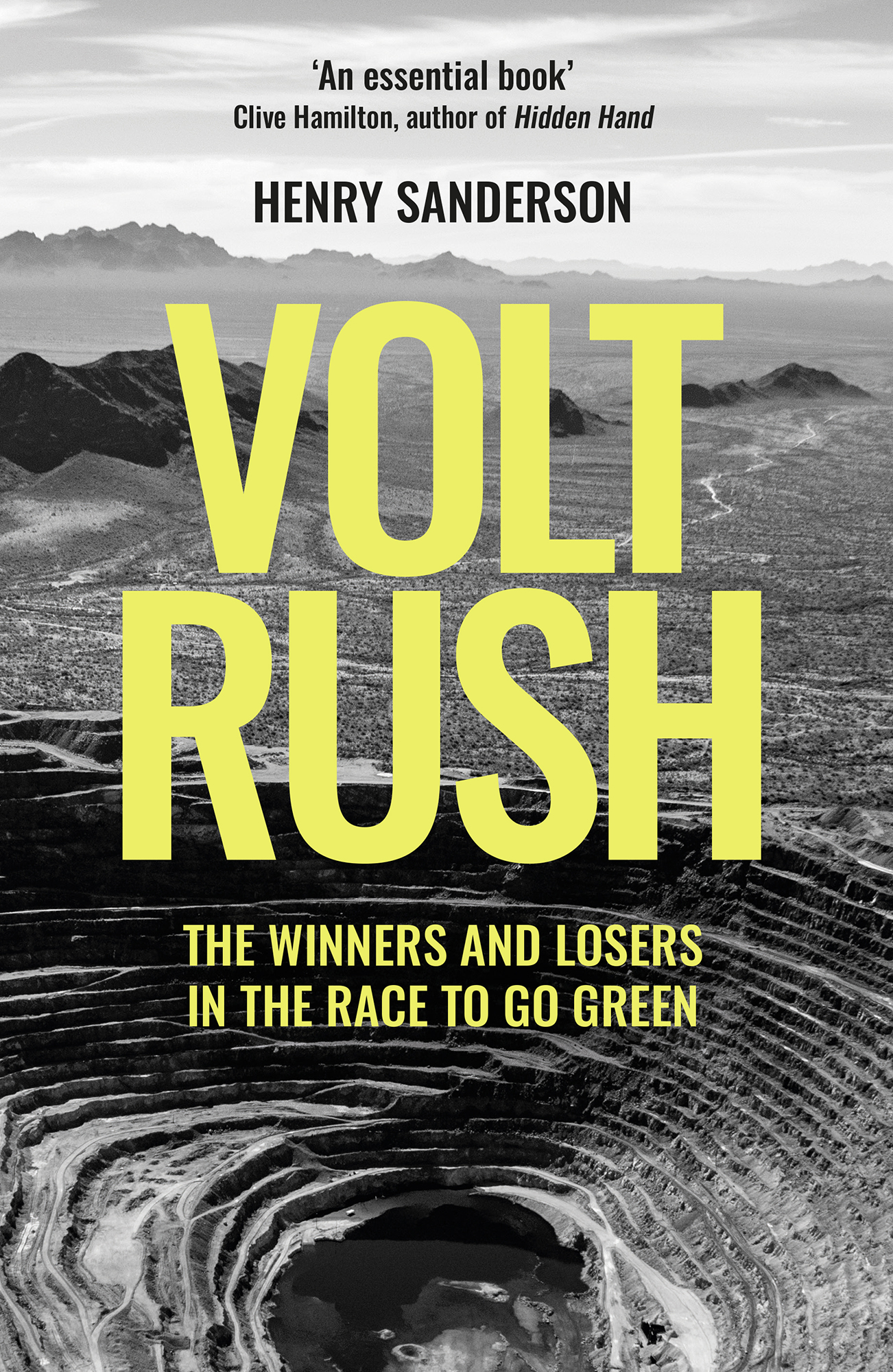

A Oneworld Book

First published by Oneworld Publications in 2022

This ebook edition published in 2022

Copyright Henry Sanderson 2022

The moral right of Henry Sanderson to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs, and Patents Act 1988

All rights reserved

Copyright under Berne Convention

A CIP record for this title is available from the British Library

ISBN 978-0-86154-375-5

eISBN 978-0-86154-376-2

Typeset by Geethik Technologies

Oneworld Publications

10 Bloomsbury Street

London WC1B 3SR

England

Contents

To Claudia and Jamie

Introduction

We have to scale battery production to crazy levels that people cant even fathom today.

Elon Musk, Tesla CEO

In mid-2020 as the world settled into lockdown, we decided to get an electric car. Our son was seven months old and I had begun to think seriously about his future and whether the world would act quickly enough to mitigate the threats of climate change. Shares in Tesla were soaring, and the carmaker was on the cusp of becoming the most valuable in the world, despite the fact it made a fraction of the eleven million cars a year produced by Toyota. Teslas Model 3 had been the UKs bestselling car that April and our friends had started to take the plunge. I knew that our sons future would depend on decisions we made now, not later. Even as the pandemic had halted global economic activity the news was still grim: a Siberian heatwave had pushed up global temperatures to their second-highest on record. The well-known impacts of climate change stemming from our consumption of fossil fuels had not taken a break. So, I placed our old two-door petrol car for sale and started to look for electrics to rent. Google informed me that one popular search topic was: Will petrol cars be worthless?

Electric cars were the ethical consumer choice. It was a seductive idea: we could change the world by slightly altering our current lifestyle with a marginal amount of sacrifice. Buying a green The car leasing company I used promised a world where cars go hand in hand with the environment. I imagined myself charging my car in the future and wondered how we would start to perceive petrol cars. Would driving one start to seem like an act of wanton vandalism to the planet, a thoroughly anti-social provocation?

For seven years I had lived in Beijing at the tail-end of Chinas thirty-year car boom. I would still wake up with memories of what it had felt like to live there: the dry grating taste at the back of my throat, the hot breath behind my mask (long before Covid) and the tightness in the centre of my chest. I remember watching the red taillights on giant ring roads flowing into a dusk the colour of dirty sink water and feeling unable to escape the city of over twenty million. On some days Beijing felt like a postcard from the end of the planet. Chinas car demand seemed like an unstoppable juggernaut an urge to consume that would eat up whole cities, and then require new cities to be built for the cars.

The growth of Chinas car market in my lifetime is alarming. To make a meaningful difference to climate change we will need to scale up the electric car fleet rapidly. The current stock of electric cars globally is around ten million, less than twice the number of cars in Beijing and only one percent of the global total. There are over one billion cars globally on the roads. We will also need to replace buses and trucks with electric versions, as well as ships, ferries and even planes. All this will require batteries on a scale unimaginable a few years ago. Teslas South African-born founder Elon Musk had built a vast battery Gigafactory in the desert of Nevada to supply his electric cars as well as the batteries to store renewable sources of energy. But he was not alone: across China a new factory was being built every week in 2020.

Through my work as a Financial Times journalist, I had covered the raw materials electric cars needed: the lithium, cobalt, nickel and copper, as well as aluminium and steel. The harder I looked at the supply chain and who was responsible for these metals, the more I understood the shift in economic power that this transition would bring. While Musk and Tesla took all the media attention and limelight, there was a shadow world of billionaires who were also set to get rich. A gold rush had begun.

In the Democratic Republic of the Congo I saw private jets landing at the small green and white airport in the mining town of Kolwezi while all around children and families mined for cobalt by hand; in Chile I stood in the searing heat of the Atacama Desert overlooking giant pools the size of Manhattan where lithium was extracted; and in China I visited battery factories and lithium plants running twenty-four hours a day using coal-fired power next to fields where buffalo roamed freely. All this was part of the electric car supply chain. A host of companies were even planning to mine the deep sea for these minerals, opening up one of the last unexplored wildernesses to extraction.

Every day, we rely on metals and minerals to power our iPhones and transmit our electricity. Digital technologies give us a sense that we live in an ethereal economy untethered to the material world. In fact, we are mining more minerals than at any time in our history, a dependence that is only set to increase. Despite talk of artificial intelligence, the internet of things, and an imminent takeover by robots, our societies have in many ways not moved on from the practices of the past, when the need for oil drove Europeans to carve up the Middle East.

The consequences of the transition will not just be economic they will also be environmental. Extracting and processing these minerals requires large amounts of energy and pollutes local ecosystems. This fact is often hidden in debates about a transition to renewable energy and electric cars. Every product we use has contributed to global emissions, both through extraction of raw materials and manufacturing. Mining is estimated to contribute around ten percent to global carbon emissions. It is an unavoidable industry: to make steel we need coal, and to make batteries we need lithium, the worlds lightest metal with the highest electrochemical potential. The electric vehicle (EV) revolution is green at its core but there are many choices to be made in the way it is executed that will affect both the environment and global power dynamics.

Green energy evangelists tend to assume that a fossil-free future will be without conflicts. Bill McKibben, a well-known activist, wrote that if the world ran on sun, it wouldnt fight over oil. Yet the demand for raw materials to build our clean energy infrastructure is as geopolitical as the age of oil. Countries that are able to become a part of these new clean energy supply chains will benefit, while those who cannot will suffer.

The transition to clean energy has already deepened geopolitical tensions between the West and China. Over the past decade, China has obtained a dominant position in both clean energy technologies such as batteries and solar cells and the raw material supply chains that underpin them. While many of these minerals are not rare in the earths crust, they are mostly processed in China into usable forms. Its likely the lithium and cobalt in my car were mined in Australia and the Congo yet processed in The electricity was probably generated from solar panels produced by a Chinese company from polysilicon made using coal-fired power in Xinjiang province. And the copper was almost certainly refined in one of Chinas hundreds of copper smelters. Without China, we cannot move towards a green, battery-powered future. As we move towards greater energy independence, these supply chains remain our greatest vulnerability.