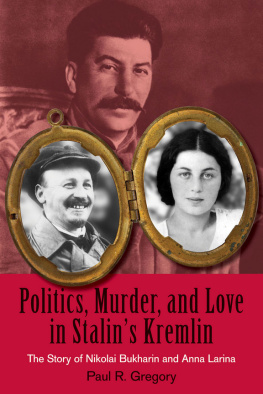

Politics, Murder, and Love in Stalin's Kremlin

The Story of Nikolai Bukharin and Anna Larina

Paul R. Gregory

HOOVER INSTITUTION PRESS

Stanford University

Stanford, California

The Hoover Institution on War, Revolution and Peace, founded at Stanford University in 1919 by Herbert Hoover, who went on to become the thirty-first president of the United States, is an interdisciplinary research center for advanced study on domestic and international affairs. The views expressed in its publications are entirely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the staff, officers, or Board of Overseers of the Hoover Institution.

www.hoover.org

Hoover Institution Press Publication No. 579

Hoover Institution at Leland Stanford Junior University, Stanford, California, 943056010

Copyright 2010 by the Board of Trustees of the Leland Stanford Junior University

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without written permission of the publisher and copyright holders.

First printing 2010

16 15 14 13 12 11 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Manufactured in the United States of America

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum Requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.481992.

Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available from the Library of Congress

ISBN-13: 9780-817910341 (cloth : alk. paper)

ISBN-13: 9780-817910358 (paperback : alk. paper)

ISBN-13: 9780-817910365 (e-book version)

Foreword

by Robert Conquest

P AUL GREGORY HAS A GREAT RECORD of investigating the realities of the former Soviet regime. He has helped restore truths long hidden in murky, dusty files, into whose still incompletely explored riches he has been one of the most helpful investigators. In a number of books that have been welcomed and praised in Russia as well as in the academic West, Gregory has added much in the way of economic and organizational understanding. If there are still details to be filled in, and some to be corrected, that is always true of serious historical research. His present book, however, is not in this category. It is, as he says, for the general reader.

There is a whole literature on the recovery of the realities of an intellectually as well as physically repressive political and social order. And within this genre lie many human tragedies. What Gregory has done here is to give that background as the locus of personal dramas centered on the acts and motivations of three of the most revealing figures in the frightful Soviet maelstrom (Bukharin, his wife Anna, and Stalin), in a series of vignettes in which the dramatis personae meet in a long struggle for two of them merely to survivea struggle the Bukharins lost. Coming from the party elite, they do not so much typify as illustrate the already raging mass terror of unpolitical, non-intellectual victims, whom they then joined.

Just as Gregory has avoided the formality of the lecture hall, so has he actively rejected dry formalism. His scenes are centered on the emotional drama, on the acts and feelings of the protagonists.

The political infighting stands out in the context of character and feelingmore effectively so than in pure fiction.

Many academic readers are professionally concerned with the whole fearful ambience of Stalinism. Here is what many others will find readable: a story told to show the horrors of fate, of personal mistreatment and suffering by real people. Their thoughts and feelings were often ill-suited to the crushing environment and are often most visible in the vivid context of Gregory's feuilletons, which come together as tragedy.

At this level, the book works as a romance and even as a thriller. Thus, it is suitable for a broad, non-specialist audience, which will be instructed as well as entertained.

Preface

T HIS BOOK TELLS THE TRAGEDY of one death and one ruined lifethat of Stalin's most prominent victimsNikolai Bukharin and his wife, Anna Larina. Stories such as theirs may offer more insights than general accounts of Stalin's purges. Their saga contains all the elements of high drama: love and devotion interspersed with intrigue, betrayal, hope, weakness, friendship, navet, endurance, optimism, bitterness, and ultimate tragedy.

Nikolai Bukharin was a founding father of the new Bolshevik state at the age of twenty-nine. Well educated and charming, he became an intimate of the exiled Lenin, who later dubbed him the favorite of the party. A rising star, Bukharin was the editor of Pravda, and he joined the elite Politburo following Lenin's death. After forming an alliance with Stalin to remove Leon Trotsky from power, Bukharin crossed swords with Stalin over their differing visions of the world's first socialist state.

Anna Larina was the daughter of a high Bolshevik official, one of Bukharin's closest friends. She was three years old at the founding of the Bolshevik state. They married seventeen years later, on her twentieth birthday. Following Bolshevik custom, there was no formal wedding. Anna simply moved into Nikolai's Kremlin apartment, and they were scarcely apart until his arrest in 1937. Theirs was a remarkably close relationship based on friendship and then love.

The story of Nikolai Bukharin and Anna Larina begins with the optimism of the socialist revolution, but turns into a dark tale of foreboding and then terroras the game changes from political struggle to physical survival. Theirs is also a tale of courage and cowardice, strength and weakness, misplaced idealism, missed opportunities, bungling, and, above all, love.

Stalin was purported to have quipped that one death is a tragedy; a thousand is a statistic. Nikolai Bukharin was only one of the millions of the dictator's victims. Most were ordinary people, whereas Nikolai and Anna belonged to the Bolshevik elite. But their story takes us from the statistic to the tragedy, and provides a more enduring understanding of Stalin and Stalinism than the tally of the millions he ordered killed.

Bukharin's tale also sounds a cautionary note for those sympathetic to benevolent dictatorships as a way of escaping national poverty. The dictator can turn out to be a Stalin instead of a Bukharina Saddam Hussein or Robert Mugabe instead of Singapore's Lee Kuan Yew. Of the possible successors to Lenin, Bukharin most clearly spelled out a vision, which today would be called socialism with a human face. His loss suggests that Stalin's victory was predetermined by factors deeply embedded in the Bolshevik revolution. Bukharin proved helpless against a ruthless competitor who thirsted for absolute power.

PAUL GREGORY

Houston and Palo Alto, December 2009

Acknowledgments

T HIS BOOK TELLS THE TALE of Nikolai Bukharin and Anna Larina's losing battle with Stalin. Politics, Murder, and Love in Stalin'sKremlin grew out of conversations with John Raisian, director of the Hoover Institution, and Richard Sousa, deputy director and director of library and archives. They encouraged me to use my explorations of the Hoover Archives to write a book that would appeal to both professional and general readers. After reading the transcript of Nikolai Bukharin's crucifixion before the central committee plenum of February 1937, I knew I had found an epic tale that would draw readers into the dark labyrinth that was Stalin's Russia.